When William Wrigley took a majority share of the Cubs in 1921, he transformed the way baseball was advertised. He dedicated himself to increasing the game’s appeal and pulling in a diverse audience. Through the introduction of Ladies’ Day and the radio broadcast of every Cubs’ game, Wrigley’s innovations redefined both baseball and marketing. The story of Cubs advertising in the 1910s helps highlight the innovative nature of Wrigley and provides a peek at the origins of several contemporary baseball customs.

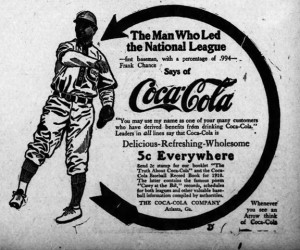

In the early years of the decade, perhaps because the Cubs hardly needed an introduction, the internal advertising was limited to small reminders published each game day that instructed fans on how to purchase tickets. Though external advertising was a more prominent staple due to the increasing commercialization of American society, it incorporated the Cubs into broader campaigns, rather than specifically featuring the club. In 1910, Coca-Cola launched the first part of its decade-long advertising campaign structured on the most famous American athletes. One of the first to be featured was Cubs’ first baseman Frank Chance. The ad boasted his fielding percentage, .994, and a less-than-snappy statement from him, saying, “you may use my name as one of your many customers who have derived benefits from drinking Coca-Cola.”1 The other prominent ad campaign was that of Old Underoof Whiskey. The Chicago whiskey company featured the Cubs (and also the White Sox) in various ads from 1910 to 1911.2 Each ad contained a sketch reflecting the dominance of the Cubs in relation to the team’s opponents and used word play to link the drink to each unique depiction.

After adding marketing mogul Albert Lasker to the ownership group in 1914 and moving to Weeghman Park, advertising expanded to include special events, giving the Chicago Cubs more of a community appeal. The park hosted a Wagner opera in 1915, as well as a Knights of Columbus day and several benefit games for the families of those who died during the Eastland disaster. Later that year, the club further diversified its advertising methods by joining the White Sox in promoting Steele’s Game Of Baseball, a tabletop baseball game that promised the players “one tense, gripping situation follow[ing] another so rapidly that the breathless interest is sustained.”3 The Cubs were now part of people’s home lives, rather than simply public displays.

This process of community engagement was aided by WWI, as the owners donated Weeghman Park (and then Cubs Park) to various benefit groups in 1916 to support European soldiers’ families and in 1917 to supply funds for American soldiers in Europe. An example of the times, the first event, labeled “the most important outdoor night spectacle of the year,” was hosted by the Aryan Grotto, a subsection of the Freemasons.4 Another event, under the umbrella of the Red Cross, was a performance by 11-year-old dancer Florence Smith that raised money to buy tobacco for American soldiers in Europe.5 Weeghman Park housed a number of other Red Cross benefits, gathering together various community groups, such as the police,7 high school bands, and local charity organizations. These events drew thousands of Chicagoans to the park, a practice that continued for the Cubs throughout the coming decade.

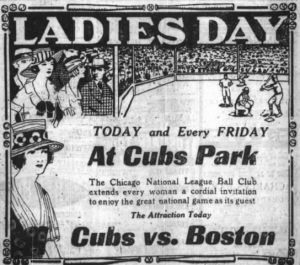

By 1919, the Cubs had assumed an even more expansive and diverse campaign, headed in large part by Bill Veeck. In addition to reintroducing Ladies Day,9 Veeck invited numerous amateur and charity teams to compete in exhibition games, such as the one between the army and navy that took place on August 23, 1919. Wrigley and Veeck further committed to Lasker’s work of integrating the club with the community, particularly in relation to humanitarian and military personnel. They allowed Christmas trees to be sold there in both 1919 and 1920 and ensured the park was home to the largest display of Fourth of July fireworks in the city.8

Veeck and Wrigley also did much to advertise the Cubs games themselves. They enlarged daily game advertisements and used more exciting language, along with more bombastic pre-game ceremonies. In 1919, the pair eschewed the tradition of having a local no-name politician throw out the Opening Day first pitch, instead selecting a pair of WWI sergeants, including the club’s own Grover Cleveland Alexander.

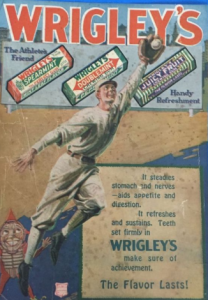

The individual, product-related ads continued, particularly in relation to Wrigley Gum, but these occupied a smaller part of the advertising process. The product’s ads consistently featured baseball themes and various Cubs players, although many were nameless, wearing generic Cubs uniforms. Wrigley and Veeck expanded the nature of baseball advertisement, placing themselves in charge of it, rather than merely allowing large corporations to use individual players to promote Cubs baseball.

Whether spurred by the need to increase attendance during periods of poor play or simply responding to the commercialization ushering in the Roaring Twenties, the baseball magnates pushed innovative advertising methods and messages. They promoted the Cubs as a fundamental aspect of Chicago’s community and brought the team into people’s homes, two elements that have become integral to baseball’s development and consumption.

1 Chicago Inter-Ocean, July 7, 1910.

2 Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1919.

3 Chicago Daily Tribune, December 19, 1915.

4 Chicago Daily Tribune, July 6, 1916.

5 Chicago Daily Tribune, December 19, 1915.

6 Chicago Daily Tribune, August 11, 1917.

7 Chicago Daily Tribune, July 22, 1917.

8 Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1919

9 Chicago Daily Tribune, July 16, 1920.

Mary is a great addition to your site. Lots of new perspectives on Cubs history rather than the old retreads.