As the Cubs continue their three-year, $500-million renovation of Wrigley Field, numerous changes will be made, many of which are sorely needed—renovated clubhouses, batting cages, bathrooms and so on. One of the biggest additions is the addition of the 42-by-95 foot video board in left field.

It’s hard to miss. The view isn’t crystal clear from my vantage point in Davenport, IA, but all kidding aside, simply comparing its size to the center field scoreboard gives a sense of the dimensions. Forget about the rooftops—fans can just hang out on Sheffield and watch the game from there, at least until the right field bleachers are completed and that viewing angle is removed. With a structure that size, the question being asked is whether it will have an effect on batted balls.

It’s a reasonable question—throw something of that size up and the logical answer would be of course it will have an effect. Anything that can get in the way of the wind at Wrigley Field can potentially decrease any resistance batted balls would face, which could lead to more hits. Lucky for us, data exists with which to test this idea.

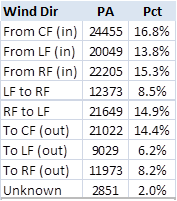

The video board is in left field, and as such would block any winds from the north. Baseball-Reference has game time weather data going back to 1991, including wind speed and direction, and this is how the wind patterns break down:

To explain, there have been over 24,000 plate appearances in which the wind was blowing in from center field at the beginning of the game, or almost 17 percent of the time. In general, winds were blowing in around 45 percent of the time, crosswinds around 24 percent of the time, and blowing out around 28 percent of the time.

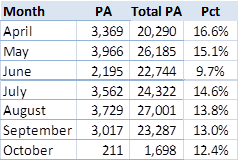

In this time frame, the winds were blowing in from left field around 14 percent of the time, not an insignificant number. This data can be refined and viewed by month:

North winds are more of a spring occurrence, perfectly logical from a meteorological perspective—winds come from the north in the colder months and from the other directions in the warmer months.

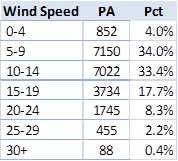

Not all winds are the same though—this shows wind speed when it’s blowing in from left field:

This doesn’t even take the kind of hit into consideration. The typical single is a ground ball, doubles and triples are often line drives hit to the gaps, and rarely do batted balls of these types rise to the height where the wind would have an appreciable effect on their trajectory.

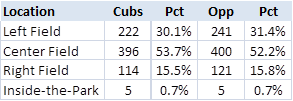

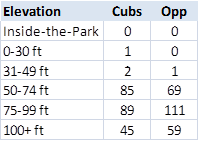

Which leaves home runs. The ESPN Home Run Tracker shows there have been 1,504 home runs hit in Wrigley Field since 2006, with the Cubs hitting 737 of them and their opponents 767. This shows the breakdown of the home runs:

For there to be an effect, the ball must be hit high enough for the video board to block winds that would have kept it in the park. I’ll make an educated guess that the left field wall is 30 feet high, and by wall I mean the outside wall, not the left field fence—the outside wall provides a wind block of its own. So, the video board might have an effect on balls hit to left field with a maximum elevation between 30 and 75 feet—lower and it doesn’t matter, and higher, the ball is above the video board’s height.

Since 2006, of the 463 home runs to left, 157 (the ones hit at an elevation between 30 and 74 feet, or around 11 percent of all home runs) might have received some boost from a video board that blocked the wind—and 89 percent wouldn’t. I could add another layer of data with home run distance, but at this point it’s an exercise in numerical masochism. If Alan Nathan reads this, I’d love to hear what he has to think on the subject.

Having written all this, there will be times when a ball will be hit and the wind patterns will be altered enough by a sign that is over 3,600 square feet, but to think this will be a daily, or even weekly occurrence is to overstate the significance the video board might have. Vice president of ballpark operations, Carl Rice, had this to say on the subject:

“We’ve done studies on the wind patterns and there’ll be some slight alterations to the wind patterns. But, they affect both teams. The wind blowing in, the wind blowing out, it all has various effects on it. We need the other video board to get up to see what the total effects are; and we’re going to do a wind study after all the boards are up and make sure it’s consistent with the study we did.

“One feeling was that when the wind is blowing in, it will knock down the wind a little bit more. But not a whole lot, it was really a small percentage that they thought it would have an effect.”

The number of balls that might be affected could be in the teens every year, and that’s being exceedingly generous. There’s much more that goes into how far a ball travels when hit, and while wind speed and direction certainly play a role, hit trajectory and initial velocity off the bat are also factors. Plus, all the weather data doesn’t take into account the changes in wind direction that occur after the game starts, nor have I even considered the positive effects that a video board could have on balls hit to center or right. That enters the land of abject speculation.

As the Wrigley renovations continue, the stories of what effect a given change will have will continue, but that doesn’t mean they’ll all stand up to close scrutiny. It’s very rare that changes in input A lead directly to differences in output B, and the video board, while an easy (and highly visible) story, is one that likely won’t have the outsize effect some suspect it will. This doesn’t mean there won’t be occasions where it alters a ball’s flight path, or that it could even prove to be the determining factor between defeat and victory. Never confuse probability with actuality—given a long enough time span, almost anything will happen. The real question is how often it will happen again.

Game time weather data from Baseball-Reference, home run data from the ESPN Home Run Tracker

1 comment on “A Jumbo Wind Screen? Or Maybe Not”

Comments are closed.