The slider. The cutter. The slutter. It goes by many names. Since arriving to the Cubs in 2013, Jake Arrieta has worked with Chris Bosio and the coaching staff to hone his best pitch into a weapon—a heat-seeking missile darting away from bats and toward the catcher’s mitt. It’s helped him transform into not just an All-Star level starting pitcher and an ace, but one of the very best pitchers in the game.

Watching him last year was both a source of joy and worry, for me. Was it too good to be true? The nature of Arrieta’s delivery is fairly volatile, and he’s already dealt with the issue of shoulder soreness in the past (he started the 2014 season a month late because of this). He isn’t a prospect that the Cubs had developed through their farm system and called up at a tender age, either. This is a nearly 30-year-old pitcher that broke in with the Baltimore Orioles in 2010 and had a career 5.46 ERA in 358 career innings at the time he arrived in Chicago. That’s not all to say that Arrieta isn’t talented, because we know he is. The Orioles knew it, too, as they took in him the fifth round of the 2007 draft and saw him rated as one of the top pitching prospects in the game.

But could the very thing that helped bring about the transformation from washed-up-prospect to Cy Young winner lead to his eventual downfall? (I mean, of course, the end is inevitable for us all.) By that, I mean the usage on his best pitch; the one that Arrieta calls a slider, grips like a cutter, and manipulates like something possessed by the spirit of Dennis Eckersley. To even begin to explore that question, we would need a better understanding of the pitch, itself. A little digging showed me that Eno Sarris, of Fangraphs and Fox Sports, had done the most work on the specific topic.

The most interesting part of Sarris’ work on the topic is differentiating between the two different types of cutters thrown by pitchers, and how they can affect your arm differently. There’s the cut fastball, which is a version of a fastball thrown by a lot of pitchers and, most famously, by Mariano Rivera. But then there’s the cutter, which is actually a form of a slider. There’s been little consistent data to show that the cut fastball causes arm injury or decreases velocity, but the feeling about the slider-style cutter is quite different:

“Dan Haren admitted to throwing the slider-grip cutter, and felt that it “absolutely” led to velocity loss (he just didn’t care because he was already losing velocity). Zack Greinke threw a cutter and a slider and felt they morphed into the same pitch… Jesse Chavez showed the slider grip on his cutter, admitted that he’d heard it led to lower velocity, but said he made sure not to “manipulate” the ball. Ben Badler at Baseball America found that scouts also felt that cutters led to velocity loss.”

So while there are two different styles of grips only the slider-style cutter is truly a risky pitch to throw, it seems. I felt I knew the answer to the question already, but I tagged Sarris on Twitter in a conversation about Arrieta’s grip to see which category he falls into.

@RyanDavisMLB @sahadevsharma @rianwatt https://t.co/Qz4foz79gJ been writing about it for a while, I do think he throws the riskier one

— Eno Sarris (@enosarris) February 6, 2016

With that unpleasantness behind me, I went forward into looking at pitchers with similar usage on their slider to check into any recent precedent. The stats team at BP helped me by fleshing out the list of all starting pitchers to throw at least 1,000 sliders in a season (Arrieta threw 1,002 in 2015) going back to 2008, when we began keeping PITCHF/x info. There was a decent list—around 25 different times it’s been done—but I had to narrow it down further to align the risk with Arrieta. I took out anyone that performed the feat in 2015, as there are no comparative results from 2016 yet. Then, to match with Arrieta’s youth, I narrowed my list to anyone under the age of 30 at the time of completing the 1,000 slider task.

The results were interesting, for sure. There were 13 pitchers in the sample, and from there I was able to research fastball velocity during the season in question and compare to the season after. And here’s the thing: fastball velocity did drop, pretty much across the board in fact, as the average fastball velocity began at 93.5 mph and fell to 92.9 mph the next season. That’s a difference of 0.6 mph, which may or may not be significant, depending on the pitcher.

Here is some more of the data, for what it’s worth, in relation to what happened to a pitcher’s ERA.

Of course, ERA is a somewhat subjective, but the same research found that H/9 and BB/9 also went up while K/9 went down slightly.

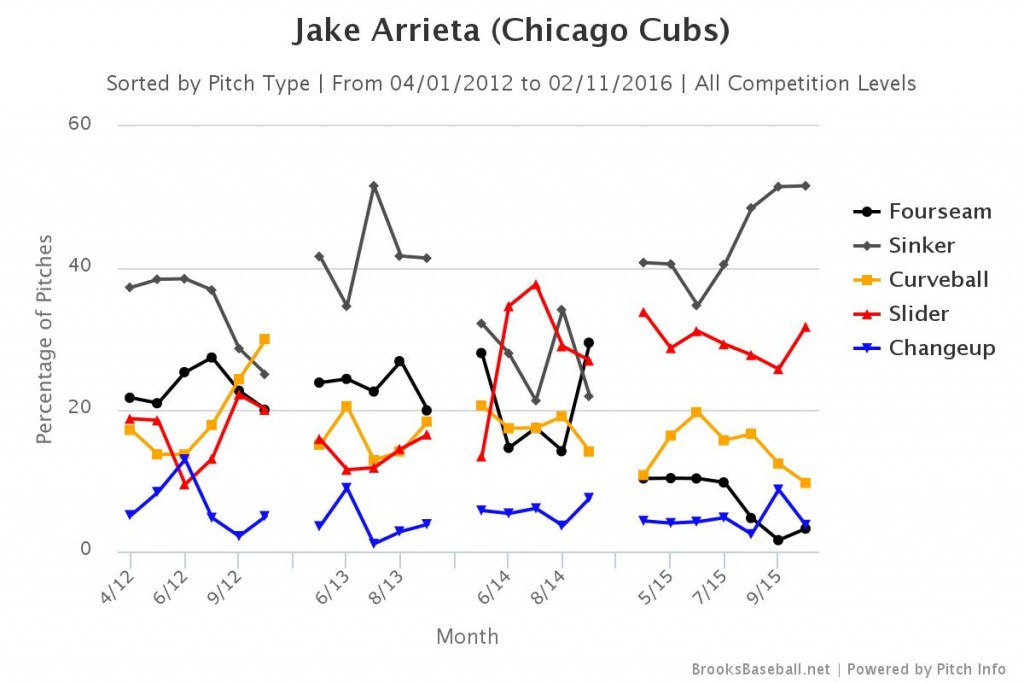

Another important factor is what Arrieta throws when he’s not throwing his slider/cutter. In 2015, that pitch made up just under 30 percent of what he threw to batters while his two-seam fastball was his most frequently thrown pitch. In fact, as Arrieta got better and better down the stretch in 2015, his four-seam fastball disappeared altogether.

It’s possible that a slight dip in velocity wouldn’t bother Arrieta all that much. The other concern is injury-related, and although no definitive studies have proven that sliders will cause major injuries, it’s safe to say that throwing the slider isn’t exactly the best for your arm. Nevertheless, we can look further at pitchers from recent years that threw a ton of sliders and see what happened to their health.

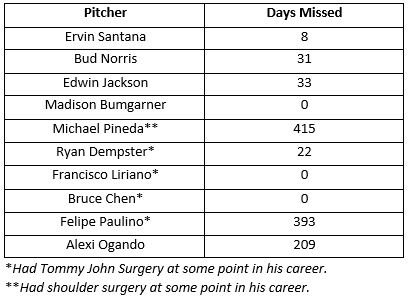

According to Jeff Zimmerman, again of Fangraphs, there is added risk in employing pitchers that throw both a high amount of sliders and a high amount of curveballs. His piece is from 2012 and lists out the top-10 pitchers in percentage of sliders thrown for 2011, which gives us the last four season’s worth of hindsight. Here is how many days each player has missed due to shoulder, elbow, or arm injury since 2012 (unrelated to a batted ball or other coincidental happenstance):

From this list, there are several pitchers who missed very few days or no days at all over the course of the last few years, successfully throwing their slider heavily and getting away with it. But half of them, however, have either had Tommy John Surgery at some point in his career or a surgery on his shoulder. And that’s not even counting Ogando, who probably could’ve had Tommy John Surgery in 2014 but elected to rehab without the surgery, or Norris, who has had several shoulder injuries in his career but has successfully avoided surgery.

None of this is proof that Jake Arrieta is going to get hurt. There’s enough information, either stated here or elsewhere on the internet, that shows the link between high slider usage and risk for injury or velocity drop. Maybe Arrieta’s unique style that features a very low four-seam fastball usage will cover any lost velocity, and maybe his overall peak physical shape will help keep him strong and avoid major injuries. But in coming off the season in which he’s thrown by far the most pitches of his career—and by extension the most sliders he’s ever thrown—there is enough reason to be worried about the amount risk tied to the grip Arrieta puts on his out-pitch.

Lead photo courtesy Robert Deutsch—USA Today Sports.

Good stuff. I don’t worry he’s a one-hit wonder; that said, I do wonder about what level of regression we’re going to see here. Many seem to assume that he’s such an obsessive fitness freak that he’ll be mostly fine. I hope that’s true.

“as the average fastball velocity began at 93.5 mph and fell to 92.9 mph the next season. That’s a difference of 0.6 mph, which may or may not be significant, depending on the pitcher.”

Any idea what an average velocity drop across the board is for pitchers in this age range?

I don’t know an exact number, but for pitchers that average just under 27 years old, a velocity drop of over 1/2 a mph, when they’re already throwing around 93 on average, would eyebrow raising. To better explain, it’s far less concerning if a 27-year-old throws 97.5 on average and then dips to 97 than it is for one that throws 93 to dip to under 92.5.

At any rate, this was just the average. A few guys didn’t see any change, while others dropped 2 mph on the fastball or as high as 3 mph in one case. Some of the drop off was shocking, including how the performance fell off as well.