“There’s no limit to how .480 this team could be.” This might sound like a sneak preview of the Marlins or Diamondbacks chapter in the upcoming Baseball Prospectus 2017 annual, but in fact was the first line of the team comment on the 2007 Cubs.

Yes, the team outlook was just a little different a decade ago. The Cubs won 37 fewer games in 2006 than they did in 2016. In fact, they were almost exactly as bad as the 2016 team was good. They ranked 27th in TAv. They managed to finish as the second-worst team in the NL for both scoring and allowing runs. Given the scathing tone of the Cubs essay that opens the chapter, the reader might be forgiven for thinking that Dusty Baker had managed the team in a way designed to secure the number one pick in the draft for Chicago, instead of a playoff berth. (Baker also failed in this respect, as the Rays and Royals were still worse, taking David Price and Mike Moustakas ahead of Chicago’s third pick, of which the less is said the better.) Baker’s tenure had unsurprisingly ended after the near 100-loss season, with Lou Piniella stepping in.

Looking back at team previews from a decade ago is an exercise designed to remind anyone of both baseball’s unpredictability and the massive extent to which both team and player fortunes can fluctuate. The 2007 Cubs were in fact not a .480 team, but a division-winning .525 team, with a Pythagorean record two wins higher than their actual 85. The new contracts GM Jim Hendry gave to Aramis Ramirez and Derrek Lee proved fruitful, as both supplied an OPS north of .900, and Ramirez posted a career-high WARP of 5.2.

There are perhaps no more fascinating examples of complex career arcs than a pair of pitchers from this Cubs chapter: one of the projected starters for this 2007 team, the 27-year-old Rich Hill; and the two-sport college star, 2006 draftee Jeff Samardzija. Both have appeared in the BP Annual in each year of the past decade, both have performed at an All-Star level at some point in that period, and both career paths have veered wildly between that extreme and the replacement level end of the spectrum.

As Hill’s player comment concludes, “No-one ever doubted that Hill’s power fastball/curve mix could beat major league hitters,” although whether it actually would seemed in doubt for a while. Hill finally established himself as a major league starter following his third call-up, following a brief disastrous stint in 2005 and four similarly disappointing starts in May 2006. The left-hander eventually made a successful transition to the tune of a 2.93 ERA over the last two months of the season. PECOTA projected that success to continue with a WXRL (Wins eXpected above Replacement Level, the WARP equivalent at the time) of 3.8, second to only Carlos Zambrano on the Cubs staff.

Samardzija’s chances of both choosing to stay in baseball and performing well enough to do so were considered low enough that he was relegated to the Lineout section. Although on a pure talent basis he was regarded by many as a late first-round pick, praise was not exactly heaped on the 22-year-old.

“Based on what we’ve actually seen…there’s no way Jeff Samardzija should be in this book,” begins the comment. His “laser-straight” 96 mph fastball wasn’t fooling many hitters, and his breaking pitches weren’t much help. He still posted a 2.70 ERA in his pro debut, but struck out just 17 and walked 12 over 30 innings. By all accounts, Samardzija was the definition of raw, and it wasn’t even clear that he was going to stick with baseball, given his prowess as a football player. The Annual agreed, suggesting that 2007 “may be his only chance to be in a baseball book.”

The $10 million major league deal the Cubs gave him in January 2007 suggested otherwise. Samardzija signalled his commitment to baseball and promised to give back all of his $2.5 million bonus if he changed his mind. The move surprised many, including his own family.

“I honestly thought we were going to the NFL,” admitted Jeff’s dad, Sam, noting that his son would have been a first-round pick. Despite the commitment, Kevin Goldstein featured the big righty in the “Don’t Believe the Hype” section of his State of the Systems report for the NL Central in March 2007. A few weeks later, Goldstein quoted a scout as saying “he’s more raw than refined, and just kind of weird”.

PECOTA was more or less correct on Hill; clearly we can predict baseball. Hill actually exceeded expectations, increasing his K/9 to 8.4, dropping his BB/9 below 3, and coming close to 200 innings. DRA-based WARP puts his value that season as 4.8 wins, with a clearly above-average 91 cFIP, a tremendous first full season that helped the Cubs to that 85-77 record and a division title. The future was bright. Prognosticators seemed to be similarly accurate on Samardzija, who stumbled to a 4.57 ERA in just over 140 innings across High-A and Double-A. The Shark somehow struck out just 4.1 batters per nine, while giving up more than 11 hits per nine.

A year later, he barely slipped onto the back of Goldstein’s top 11 prospects for the organisation. The upside was still evident, but the range of outcomes was huge and the signs were not good: “One can find scouts to project Samardzija as a future ace or All-Star closer, and one can find scouts who don’t think he’ll ever get out of the minors. One cannot find a good precedent for a player with Samardzija’s numbers turning into a quality big-league contributor.”

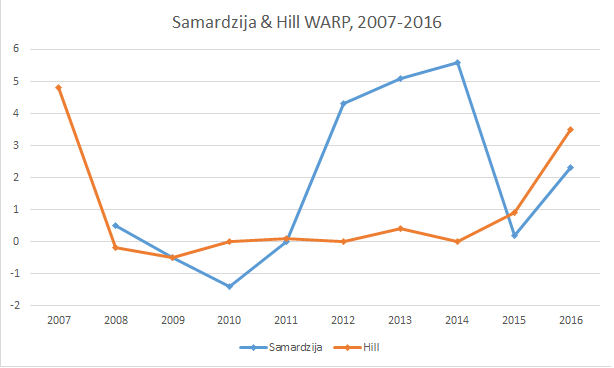

At this point, a graphical representation of how these careers actually panned out following 2007 seems appropriate. Below is a line graph representing the annual WARP for each pitcher in every year of the last decade (Samardzija did not make any MLB appearances until 2008, hence his absent data point).

The eagle-eyed reader, either from this graph or Hill’s BP player card, may have noticed that his combined WARP over the same spell is still 0.3 wins short of the 4.8 he put up in 2007, and it was not until the ninth year that his combined IP total in the subsequent nine years surpasses that of the 2007 season. Samardzija went from divisive prospect to promising reliever, to maddening reliever, from there to surprisingly useful starter, back to maddening and finally, in perhaps the strangest twist of all, essentially average.

Annual player comments are almost as tumultuous as that graph. Following his promising 2007, Hill was praised for not overusing his curveball (2008) before the tone sadly shifted to his “always-tenuous grip on the strike zone” and “wildness” (2009, 2011 & 2014), his severe shoulder (2010) and elbow issues (2010, 2012, 2013). Just a season removed from his strong 2007 campaign, Hill left Chicago in early 2009, traded to Baltimore for a player to be named later.

As the health issues threatened his career, Hill also transitioned to relief, not making a major league start for 5 years from 2010 onwards. It didn’t help; Tommy John surgery cut short his 2012 campaign. Amidst the injury issues and on-field struggles, Hill and his wife Caitlin tragically suffered the loss of their two-month old son Brooks at the start of 2014. In what seemed to be a depressingly final assessment of his career, the 2015 Annual lamented that it was “nearly physically impossible for him to pitch”.

While Hill’s career in Chicago suffered a swift and premature decline, Samardzija made his MLB debut in a surprisingly useful second half stint in the bullpen in 2008, then completely failed to build on it in the next two seasons, including a 2010 in which he walked more than twice as many hitters as he struck out in a woeful 19 1/3 innings. Compared to Samardzija, Hill’s control was pinpoint. The Shark was slammed in player comments as an “inconsistent mechanical mess” (2009) with “precious little to show he was worth the investment” (2010) and, perhaps most damningly, a “latter-day Todd Van Poppel” who might be able to provide value in middle relief, if the Cubs were lucky (2011).

Naturally, after a decent 2011 in relief, Samardzija came out and did what van Poppel never could: put together a full season as an effective starter. By late 2012, Ben Lindbergh was calling Samardzija a “dependable arm”; by 2014, the Annual was marvelling at the fact that he had become a “solid second starter,” even if some still weren’t happy that he wasn’t an ace. Samardzija then paid off for the Cubs when he and Jason Hammel were dealt to Oakland in mid-2014, a move that brought back top prospect Addison Russell.

Naturally, now that a dependable baseline for Samardzija had been established, a near replacement-level season on the south side of Chicago followed in 2015 as the White Sox tried and failed to improve his approach with a greater focus on his cutter and slider. Once he arrived in San Francisco on a 5-year, $90 million deal, he settled in for 200 innings as a league-average starter; something that he had rarely, if ever, been projected as. Across the bay, Hill was also defying expectations.

To the delight of curveball fans everywhere, 2015 wasn’t quite the final chapter of Hill’s career. After pitching 21 2/3 innings with a 2.93 ERA – but also a walk per inning – as a reliever for the Nationals AAA affiliate in Syracuse, Hill decided he wanted a chance to start. In a route back to relevance that could have come straight out of a baseball movie if it wasn’t so implausible, Hill asked to be released, then signed with the independent Long Island Ducks for two starts. He was quickly picked up by the Red Sox and found his way into their MLB rotation in September 2015 for four more, took a discount one-year, $6 million deal with the A’s because they would guarantee him a starting spot, got traded to the Dodgers mid-season and finally – nine years after his breakout season – rejoined Los Angeles on a three-year, $48 million pact at the age of 36.

Through it all, Hill baffled major league hitters, striking out 165 of them in 139 1/3 innings while also posting the best walk rates of his career. Abandoning the restraint he was once praised for with the curveball, the left-hander went to it as frequently as his fastball and proved that praise was misguided. Hill, in fact, superbly underlined a 2015 comment about Samardzija; he “illustrates that there is no ideal way to build an arsenal”. By cFIP, Hill was the sixth-best pitcher with at least 100 innings in 2016; by DRA-, he was fourth.

After two career paths that could not be more different, Hill and Samardzija will find themselves projected to offer very similar value in 2017, both in completely different ways to those you might have expected in 2007. Hill is a high-risk, high-upside option who might only pitch 120 innings but could do so as one of the ten or fifteen best starters in the game. Samardzija, instead of being an ace or a dominant closer, is somehow a workhorse who has pitched over 200 innings in each of the last three seasons without striking out or walking a particularly notable number of hitters. They both secured multi-year deals to start on contending teams in the NL West. They may well face each other on one of the nineteen occasions that the Giants play the Dodgers in 2017. There are some things that have not changed: Hill still has an outstanding curveball; Samardzija can still bring the heat. Both remind us that there are very few constants in baseball.

Lead photo courtesy Dennis Wierzbicki—USA Today Sports