When the Cubs signed Jon Lester in December 2014, it signaled a turning of the corner for the franchise. Even though it is widely accepted that free agent pitchers older than 30 are the riskiest and the least efficient way to spend money in baseball, the Cubs were ready to compete with their emerging positional core, and the team needed starting pitching. So, given that the team was going to spend on pitching in the market, they wanted to find the safest bet possible to age well, and Jon Lester fit the bill.

Why? He’s durable, he doesn’t rely on premium velocity, and he uses five pitches which he locates very well. These are all skills that tend to age more gracefully than premium velocity or movement, which can disappear in an instant with a single injury. When the deal was signed, Andy Pettite was used as a hopeful comparison – a pitcher who gradually reduced his fastball usage into his thirties as his velocity started to decline, and instead started leaning more on cutters and sinkers, getting by on deception and contact management. It worked – in his age 41 season, Pettite pitched to a 3.74 ERA in 30 starts, which is nobody’s version of an ace, but a reliable mid-rotation innings-eater that a team could count on.

For the first two years of his six-year contract, Jon Lester was excellent, producing nearly 10 WARP, finishing second in Cy Young voting in 2016, and anchoring a World Series-winning rotation. In 2017, however, Lester started to show the first signs of a potential decline. His 23.6% strikeout rate was his lowest since 2013 and his 7.9% walk rate was his highest since 2011. His groundball rate declined for the second straight year, and his HR/FB of 15.8% was the highest he has allowed in his career. His 91.7 mph average fastball velocity was his slowest ever, more than one full mph down from 2016, and his 180.2 innings pitched were the fewest of any full season.

Despite all that, Lester was still effective – he produced 3.3 WARP last season, and the HR/FB ratio isn’t quite as jarring when you consider the leaguewide increase in home runs. Still, all of those numbers are trending in the wrong direction, and the fear is that they could be foreshadowing an even more precipitous decline in the coming years.

Curious to find the cause behind those numbers, I dug into Lester’s splits and pitch selection to see if we could explain some of Lester’s struggles above and, hopefully, find some reason for optimism over the next three years. The first thing I noticed when looking at Lester’s splits in 2017 was just how poorly he fared against righties. Lester had one of the better years in his career against lefties last year, but that success was more than offset by the damage inflicted by righties.

- Basically all of the increase in damage was done by righties

| Year | OPS Allowed vs Lefties | OPS Allowed vs Righties |

| 2017 | .554 | .807 |

| 2016 | .540 | .621 |

| 2015 | .658 | .662 |

| 2014 | .696 | .617 |

| 2013 | .670 | .712 |

Interestingly, Lester’s HR/FB allowed was almost identical between righties and lefties (15.7% vs 16%), but righties hit fly balls at a much higher rate (35% vs 24%) and, as a result, were responsible for 22 of the 26 home runs that he gave up.

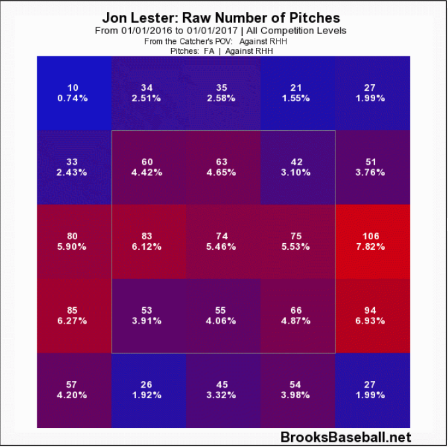

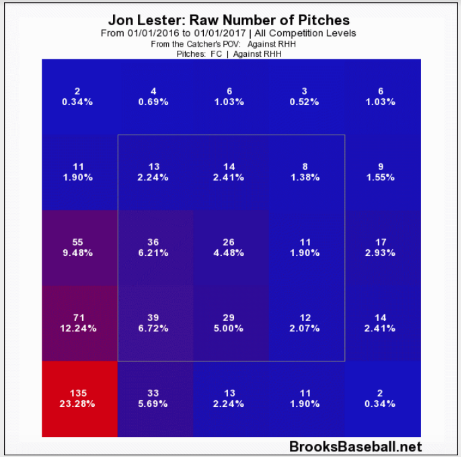

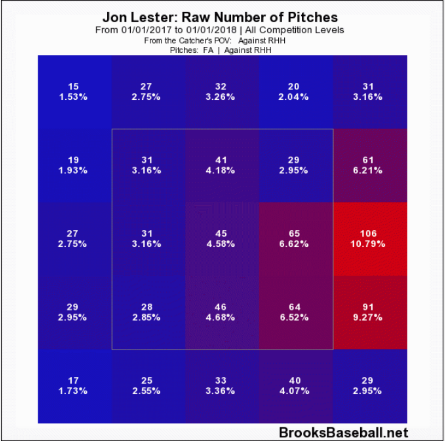

That discrepancy in batted ball profile led me to look at Lester’s pitch mix and location against righties, and right away I noticed a startling difference. Below are heat maps showing four-seam fastball location against righties in 2016 (top) and 2017 (bottom), courtesy of Brooks Baseball:

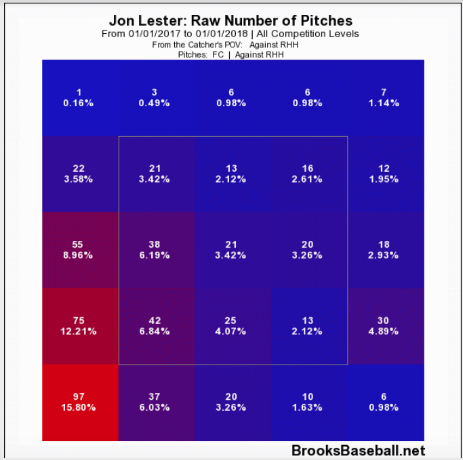

Notice that in 2016, Lester worked the four-seamer to both sides of the plate, both keeping it away from righties, and also using it to pound them inside. However, in 2017, Lester stayed almost exclusively away from righties, rarely challenging them in. We’ll never know the exact reason why, but my suspicion is that it is a side-effect of Lester’s drop in velocity – down a few ticks from 2016, perhaps he didn’t have the same confidence that a fastball in would result in either jamming the hitter or a whiff, and so he chose to play it safe on the outside corner. In contrast, Lester stayed consistent with his cutter usage in 2017:

We can see that Lester consistently keeps his cutter low and in to righties. When preceded by an inside fastball, this works very well – both pitches look very similar up until the late movement by the cutter either moves the ball off the barrel of the bat or generates a whiff. It’s less effective when the preceding fastball is off the plate away (as it was for much of 2017) and the hitter is easily able to distinguish the difference between the two pitches. This is the idea behind pitch tunneling – throwing pitches that look similar at the point when the hitter has to decide to swing, but then they end up at different locations. And ever since the introduction of pitch tunneling data, Jon Lester has been held up as the poster boy for reaping the benefits of tunneling.

However, the numbers support the assertion that Lester did not tunnel well against righties in 2017, and that may have contributed to his struggles. Against righties, two of his most used pitch sequences are fastball-cutter and cutter-fastball (the other two are fastball-fastball and cutter-cutter, which are less interesting from a tunneling perspective). To assess their tunneling effectiveness, we will use Pre-Tunnel Maximum Distance (PreMax), which is “the distance between back-to-back pitches at the decision-making point.” The smaller the PreMax value, the closer two pitches are to each other at the point when hitters must decide to swing. So, smaller is better and the average PreMax for all pitch combinations in 2017 was 1.54. Among all pitchers who threw at least 25 fastball-cutter combinations in 2017, Lester’s 1.66 PreMax against righties ranked 97th out of 108 pitchers. Similarly, his cutter-fastball PreMax of 1.73 ranked 96th out of 105 pitchers. Clearly, the deception was not there for Lester with these pitch combinations in 2017, and he paid for it.

Another way that Lester got beat in 2017 was early in the count, and on the first pitch in particular. He has always shown an interesting tendency to use his four-seamer at a very high rate on the first pitch, throwing it nearly 50% of the time in 2017. This is actually a lower rate than in 2015 and 2016, when he led off at-bats with a four-seamer approximately 55% of the time. Whether it was due to the drop in velocity, or the fact that teams knew what was coming, Lester got ambushed on the first pitch in 2017, yielding a 1.166 OPS on balls put in play. Of course, that could be subject to small sample size flukiness (it was only 64 at-bats), but it’s consistent with our other observations that Lester became less deceptive, and the fastball is becoming easier to hit with reduced velocity.

So where does that leave the Cubs, with three years still remaining on Lester’s contract? Was 2017 the beginning of a decline, or more of a small bump in the road? It is important to note that even if Lester doesn’t provide any value over the next three seasons, it would be hard to call his deal a bust, given how well the first three years went. Still, it’s hard to say with a great deal of certainty what to expect out of the next three years. Once pitchers start to lose velocity, they almost never gain it back, especially in their mid-thirties. So, rather than hoping for a velocity spike, perhaps we should be hoping to see signs of Lester adapting.

This could mean starting off more at-bats with a curveball, in an attempt to steal some early strikes and to keep hitters from ambushing the first-pitch fastball. It could mean re-establishing the four-seamer inside against right-handed hitters, even just as a show-me pitch, to keep them from sitting on the fastball away and to increase the effectiveness of the back-foot cutter. It could also mean an increased reliance on his breaking and off-speed pitches.

Lester has all the tools of a pitcher that can age gracefully – deception, a deep arsenal of pitches with different movement profiles, tons of experience – and 2018 looks like it may be time to put those tools to use.

Lead photo courtesy Joe Camporeale—USA Today Sports

Fantastic piece.

Good but the real story lies in the half splits.