I gather box score information on a daily basis and use this process as my primary means of keeping up with what’s going on in baseball. I’m always looking for the weird or quirky—a bunt that gets stretched to a triple, a passed ball on strike three where the runners advances to second, stuff like that. I’m also intrigued by the left on base (LOB) number, particularly in connection to the runs scored. For example, in the short game played between the Mets and Cardinals last Sunday, the Mets left 25 baserunners stranded in the process of scoring three runs, whereas the Cardinals “only” left 14—that’s a lot of LOB.

This chart shows the Cubs’ games in the past month, highlighting the runs and LOB:

| Date | H/A | Opp | Res | R | H | LOB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6/22 | LA Dodgers | W,4-2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | |

| 6/23 | LA Dodgers | W,1-0 | 1 | 5 | 7 | |

| 6/24 | LA Dodgers | L,2-5 | 2 | 9 | 8 | |

| 6/25 | LA Dodgers | L,0-4 | 0 | 8 | 8 | |

| 6/26 | @ | St. Louis | L,2-3 | 2 | 12 | 12 |

| 6/27 | @ | St. Louis | L,1-8 | 1 | 7 | 7 |

| 6/28 | @ | St. Louis | L,1-4 | 1 | 6 | 9 |

| 6/30 | @ | NY Mets | W,1-0 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| 7/1 | @ | NY Mets | W,2-0 | 2 | 9 | 9 |

| 7/2 | @ | NY Mets | W,6-1 | 6 | 8 | 7 |

| 7/3 | Miami | L,1-2 | 1 | 6 | 8 | |

| 7/4 | Miami | W,7-2 | 7 | 4 | 1 | |

| 7/5 | Miami | W,2-0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| 7/6 | St. Louis | L,0-6 | 0 | 6 | 5 | |

| 7/7 (1) | St. Louis | W,7-4 | 7 | 12 | 14 | |

| 7/7 (2) | St. Louis | W,5-3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | |

| 7/8 | St. Louis | L,5-6 | 5 | 9 | 5 | |

| 7/10 | Chicago White Sox | L,0-1 | 0 | 3 | 5 | |

| 7/11 | Chicago White Sox | L,1-5 | 1 | 6 | 7 | |

| 7/12 | Chicago White Sox | W,3-1 | 3 | 8 | 5 | |

| 7/17 | @ | Atlanta | L,2-4 | 2 | 7 | 5 |

| 7/18 | @ | Atlanta | W,4-0 | 4 | 8 | 9 |

| 7/19 | @ | Atlanta | W,4-1 | 4 | 9 | 11 |

| 7/20 | @ | Cincinnati | L,4-5 | 4 | 8 | 9 |

In this totally arbitrary time frame, the Cubs were 12-12, 27th in runs scored (65) and third in LOB (172). That’s a pretty direct relationship—does it hold up to close scrutiny?

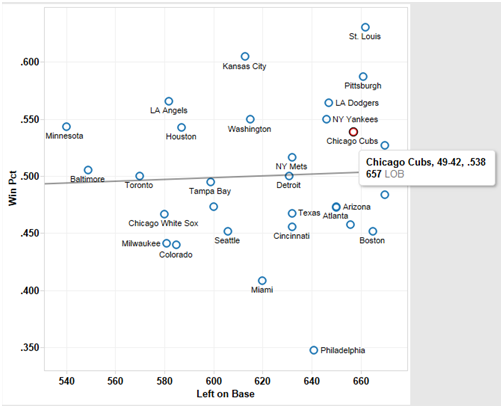

The charts that follow are taken from a Tableau data visualization I created that has various LOB data for all teams going back to 2000. All charts are from 2015 (through games of Monday, July 20th), and this first one shows where the Cubs rank in terms of LOB and plots it against team winning percent:

That trend line indicates next-to-no correlation between LOB and win percent, and in half a season, this probably shouldn’t come as a surprise. Part of the reason is that, much like grounding into double plays, LOB isn’t necessarily a bad stat, since it implies runners got on base in the first place. A runner who doesn’t reach first is one who has no chance of scoring. Stranding around 80 fewer baserunners than the Cubs hasn’t done the White Sox any favors and only shows the Sox woes in getting runners on base in the first place.

This next chart plots the total number of baserunners against win percent:

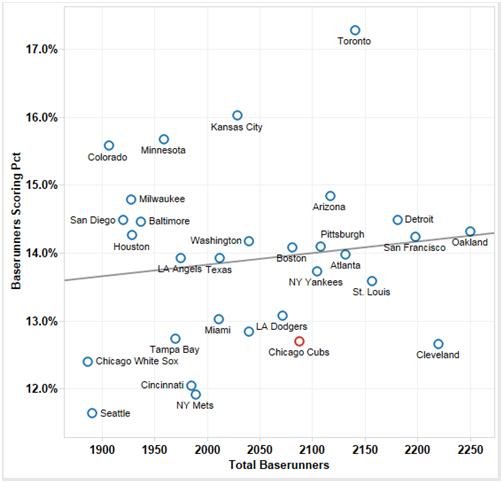

Still no strong correlation, but by now a trend should start tickling your synapses. The Cubs are in the middle of the pack in baserunners, yet are near the top in LOB—hmm. This next chart dispenses with win percent and instead plots the percent of baserunners who score:

A baserunner is anyone who is on when a hitter comes to bat. To illustrate, assume Anthony Rizzo comes to bat with Addison Russell, Dexter Fowler and Kris Bryant on base—that’s three baserunners. If Rizzo strikes out and Jorge Soler comes to bat, that’s also three baserunners—the numbers are additive, because both Rizzo and Soler had an opportunity to drive in those three baserunners. If Jorge Soler hits a grand slam, those three baserunners are credited as baserunners scored, but Soler is not—he wasn’t a baserunner.

Things begin to get downright ominous here, with a middle-of-the-pack team in terms of getting runners on base is well below average in getting them home—the major league average is around 14 percent, and the Cubs are 12.7 percent. There’s a lot that goes into this number, but the best way to look at it is in the aggregate, since breaking down these splits by base state and player leads to ridiculously small sample sizes. This is an issue that’s been near and dear to my heart for several years, particularly when I hear people wax poetically on RBIs without acknowledging that they’re largely a function of opportunity. As an aside, Nolan Arenado of the Rockies and Paul Goldschmidt of the Diamondbacks are the RBI leaders so far, with 72. This is noteworthy, because neither is in the top 25 in terms of RBI opportunities.

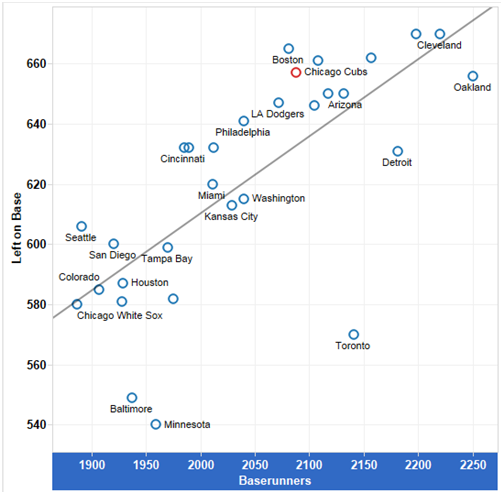

Back to the Cubs. This last chart shows the (fairly obvious) relationship between baserunners and LOB:

More baserunners, more LOB, not exactly rocket science. The point of interest are some of the teams near the Cubs—the Pirates, Giants, and Cardinals are unlabeled points just to the right of the Cubs, but there’s also the Indians and the team with the most baserunners in baseball so far this year-—the A’s. Look what that’s done for them.

There is no magic number in just about any walk of life, and baseball is no different. Having fewer or more baserunners doesn’t necessarily confer success or failure—on June 20th, the Pirates left only one baserunner on base against the Nationals. Of course, this was Max Scherzer’s no-hitter, broken up by Jose Tabata’s “HBP,” so the fact there was one LOB is no cause for celebration. Likewise, winning 2-1 obviates the fact that perhaps there were 15 LOB—it’s results, not individual factors that matter.

But in the case of the Cubs, there is cause for concern. As they continue to struggle to score runs, every opportunity to score needs to be taken seriously. Of course it is—this is nothing novel that teams haven’t known for years, but knowledge never leads directly to execution. If this were true, I’d be a scratch golfer. Part of the reason for the plethora of one-run games is the inability to turn these baserunners into runs.

No one says this situation has to last forever or that events can’t change—with the news that the Tigers are making Yoenis Cespedes available, the Cubs could add one of the better left fielders and improve their offense. Their pitching has been among the best in baseball, with the starters tied for first over the past 30 days in terms of FIP, and their relievers ninth in FanGraphs Wins Above Replacement (fWAR), which might be difficult to replicate.

One of the biggest fallacies in baseball is that home runs are the only avenue to scoring runs. It doesn’t hurt, of course, but runs are what matters, and every baserunner, even a walk with two outs, is an opportunity to score. To date, the Cubs have been getting runners on base, but haven’t been doing a good job in getting them home. As they enter a stretch of games in which they won’t play a team with a winning record until August 3rd, they’ll have to find their ability to score runs. Pitching matters, but it can only go so far. They’ve shown an ability to get on base—now they have to translate that into runs.

Lead photo courtesy of Mark J. Rebilas-USA TODAY Sports

Intersting article. I will probably catch grief for this, but I got all riled up watching the Cubs get clobbered by the Cards today and started wondering just how many runners Kris Bryant and (perhaps, to lesser extent) Anthony Rizzo have left stranded this year.

Yes, the Cubs have had a great season. But they also look terrible at times, and I am sick and tired of watching Bryant come up with men on in a close game and either whiff on something low and out of the zone, or hit a weak pop up or grounder to kill a scoring opportunity.

I have no stats to back this up, but I’d guess Bryant’s one of MLB’s leaders in runners stranded, and that he’s one of the better “garbage time” hitters in the game. Far too much, I seem him come through with a big home run, etc., late in a game that’s out of reach but fail to come through in more “clutch” situations when the Cubs need him to come through.

He’s not alone. Rizzo had a crappy day today too, and Russell, who previously seemed to be developing into a guy who was making better contact and coming through in the clutch, seems to have gone completely cold in September. It’s easy for these guys to pile it on against, say, the Reds. But when it’s the Cards? They all look like Little Leaguers.

Anyhow, for all of Bryant’s gaudy numbers he still strikes out way too much, swings at garbage but takes good pitches for called strikes, and strands too many runners when the Cubs need a rally. The picture of a dejected, befuddled looking Bryant at the top of this article says it all.

If I had an MVP vote I would not give it to Bryant. He’s really good against crappy teams, but not when his team actually needs him. It’s this problem, which afflicts plenty of other Cubs too, that will cause them to fail in October and likely drummed out of the NLCS or NLDS yet again.