On Sunday, July 24, 2016, the second-best left-handed outfielder ever born on November 21st in Denora, Pennsylvania, will stride across a dais in Cooperstown, New York, and into baseball immortality. I can say that with such certainty, before a single writer has called his name, because the 630 home runs he hit over a dazzling 22-year career are more than all but five other men managed in baseball history. And the last of those, a solo shot hit on the penultimate day of the 2009 season, came off of new Cubs’ reliever Tommy Hunter. See for yourself:

I love this sort of stuff. I love that connection to history: the knowledge I have now whenever I look at Hunter on the mound, that he is inextricably tied into the story of this incredible game. And now you know it too. And know this, also: Hunter was drafted by the Texas Rangers with the 54th overall pick of the 2007 draft—a pick which the Rangers received as compensation for the departure, on November 14th of the previous year, of free agent Mark DeRosa to the Chicago Cubs. The circle grows ever-smaller, as Hunter is now throwing bullets on the best North Side team since DeRosa left Chicago via trade on the final, wintry day of 2008.

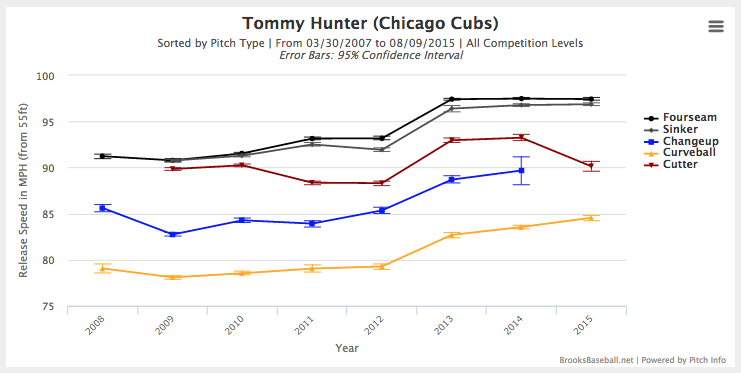

And bullets they are. When he made his debut for Texas, as a fresh-faced 21-year-old starter back in 2008, Hunter threw a pretty simple three-pitch mix: a four-seam fastball at 91, a changeup at 86, and a curveball at 79. The years since, and a 2013 conversion to a relief role, have brought a changed repertoire, in the form of a new sinker (97) and cutter (90), and a significant uptick in velocity on the fourseam (to 98) and the curve (to 85). The changeup has been dispensed with entirely. It’s probably easier to grasp the nature of the changes visually, so take a look:

That’s a major change in velocity, and it’s allowed Hunter to simplify his pitching philosophy. These days, he says, his “out pitch is anything that results in an out.” Tautological reasoning aside, he’s probably right: none of his pitches are particularly different from one another in terms of their capacity to generate either fly balls or ground balls, although his hard stuff—the cutter and the sinker—are both somewhat less likely to generate line drives than Hunter’s other offerings, which he uses mostly to set up those two.

In short, much as Travis Wood’s conversion to a relief role this season has allowed him to transform from a middling starter to a pretty-darn-good reliever, Hunter’s 2013 conversion has allowed him to reach back for a little extra gas when he needs it, further allowing him to put up some very solid numbers out of the bullpen since. For one small example: since 2013, only four AL relievers have walked fewer batters per nine innings than Hunter’s 1.74. Their names? Koji Uehara, Casey Fien, Sean Doolittle, and Dan Otero; all of whom enjoy perhaps a little more sheen than the Cubs’ Mr. Hunter. Deservedly, perhaps, but Hunter should be in that conversation as well.

In the immediate present, the Cubs would love it if Hunter could keep up his “not walking anyone” schtick: despite their generally excellent performance (by fWAR, the Cubs ‘pen is sixth-best in the National League), North Side relievers are still walking batters at an unnervingly high rate: 3.38 for every nine innings pitched. That’s the sixth-worst mark in the NL, and suggests that Hunter and his 2.08 BB/9 in in 2015 might have been targeted with this particular skill in mind. More broadly, however, Hunter’s acquisition allowed the Cubs to dispense with one of their worst relievers (at the time, probably one of Edwin Jackson, Yoervis Medina, or Rafael Soriano) and strengthen the middle of their pen, which had to that point relied heavily on James Russell and Justin Grimm, both of whom can now be saved for the later innings.

Hunter’s acquisition, in short, is just another tool that’s been added to the arsenal of Cubs’ manager Joe Maddon, who’s shown an increased ability to manage his bullpen with an artist’s touch these days. In Saturday’s game, for example, Maddon found the visiting Giants threatening with one out in the sixth inning. His options pre-trade were Justin Grimm, who has a .167 platoon OPS split, and Travis Wood, who has a .162 split. But Grimm can’t really go multiple innings at a time (he’s gone more than three outs in just 12.8 percent of his relief appearances this season, compared to Wood’s 42.3 percent), and Maddon no doubt wanted to insure against the possibility that the game would have to go to extras and Wood would be needed to go multiple innings. Pre-trade, then, he probably would have reached for Grimm. Now, however Maddon knew he had Hunter in the pen, who could not only go multiple innings (32.6 percent of his appearances have lasted more than three outs) but has a better-balanced platoon split than either, at 113 points of OPS difference.

Instead of reaching for Grimm, as he might have before Hunter’s acquisition, Maddon brought in Wood, who promptly retired lefty-Brandons—Belt and Crawford—to end the threat, before pitching a four-batter, no-run seventh inning. I’m not sure that Wood would have entered the game in that spot were it not for the depth and stability that Hunter provided to the club, and the flexibility he provided to insure the later innings, if necessary. You can never have enough pitching depth, and Maddon’s bullpen usage since the deadline is showing the degree to which he’s relying on his newfound acquisition to further buttress an already-strong area for the club.

As the season progresses, Hunter—an Indiana native who will, no doubt, be visiting his mother, who’s fighting cancer back home, a great deal this season–will seek to establish himself as a key piece of a team that looks increasingly confident and may well be playoff bound. If the team does indeed make it to October (current odds: 83 percent), it’ll be Hunter’s third taste of postseason action: he went as far as the World Series with Texas in 2010, and later threw playoff innings in 2012 and 2014, both times for Baltimore. Building on those numbers with the Cubs in the 2015 World Series would be, perhaps, the only thing that could trump—in terms of historical significance—his shining connection to the Kid from Denora, Ken Griffey, Jr. For now, though, that’s what’s up with Tommy Hunter.

Lead photo courtesy Caylor Arnold/USA Today Sports.