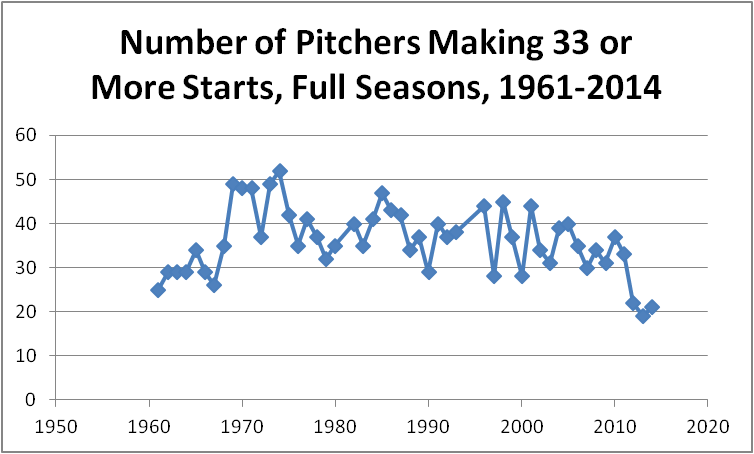

In baseball, as in all things, this is an age of specialization. Starting pitchers pitch less than ever, making fewer starts:

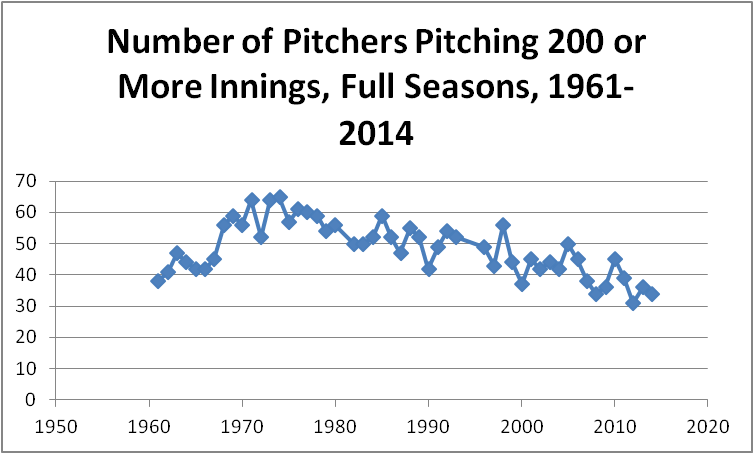

and pitching fewer innings:

than ever before. So do relief pitchers, for that matter:

We’re seeing similar trends in basketball, where players are playing as many games (or nearly as many), but fewer minutes per contest: Monta Ellis was the last player to average 40 minutes per game, and last did it four seasons ago. (Allen Iverson’s 11 such seasons already seem to belong to a different era, the way Randy Johnson’s seasonal innings totals do.) In hockey, the workload has been spread widely and evenly seemingly forever. In football, running backs, defensive backs, receivers and pass rushers all are rotating more than they used to. Back to basketball for the most famous, most recent example of the phenomenon: the Kentucky Wildcats implemented a platoon system this season, something akin to hockey’s line changes.

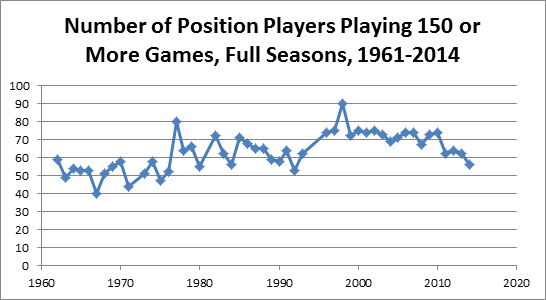

For a long time, though, baseball’s position players resisted the trend.

For as long as teams have been playing 162-game schedules, they have been spreading the workload of their pitching staffs more evenly; shortening their benches to serve the needs of the growing pitching corps; and leaning ever more heavily on their regular starters on the positional side.

That began to change late in the last decade, though, and in 2014, fewer players played 150 or more games than had done so in 1974—40 years and six expansion teams ago. Part of the reason, as the graph implies, is that steroid and amphetamine testing began in earnest several years ago. Whatever other benefits they might have derived (mostly nebulous or overstated), players absolutely used those substances to stay in the lineup, despite nagging injuries or general fatigue that would have otherwise sidelined them. That doesn’t fully explain the drop-off, though, especially because that drop happened so suddenly, and so steeply. In 2010, 74 players met that 150-game threshold, putting that season right near the historical maximum. In 2011, the number was 62, and it’s remained low ever since.

Perhaps what we’re seeing, then, is a strategic correction, a new understanding of the way players ought to be used. Artificial enhancement allowed these players to buck the trend for a while, but now that that is largely eradicated, teams are moving to the same model they’ve implemented with pitchers, and the same model their counterparts all over the sporting landscape are using to maximize the efficiency of performance. Even for good players, sometimes less is more.

Forgive the long and winding road to this point, but: the Cubs’ bench sure is deep this year. In fact, more broadly, the Cubs have gone well out of their way to ensure that they are deeper than ever, not just at the MLB level, but organizationally. They paid a premium free-agent price for Jon Lester, in order to avoid feeling pressed to trade good positional talent for Cole Hamels. They’re carrying three catchers, which will help keep each of the over-30 guys (Miguel Montero and David Ross) fresh, for however long it lasts. Even with Javier Baez, Addison Russell, and Kris Bryant stashed in Triple-A, Chicago has two solid options at each of the four infield positions, a platoon set up in left field, and ready reinforcement in both center and right. It was all done with painstaking intention, from trading a high-upside relief arm for Tommy La Stella, to giving up two years of control over Luis Valbuena for a single season of Dexter Fowler, to investing in Chris Denorfia as a fourth outfielder despite having Matt Szczur and Justin Ruggiano on hand already.

The Cubs aren’t the only exceptionally deep team in the league, of course. Most notably, the Dodgers and Red Sox are loaded with good players who can find only partial or situational playing time. Much was made, all winter, of questions like:

- When are the Dodgers going to trade Andre Ethier?

- When are the Red Sox going to trade Allen Craig? and

- What are the Cubs going to do with all these shortstops?

Well, the season has started, rosters have had to be trimmed, and players have had to be designated for assignment, and Craig, Ethier, and all of the Cubs’ shortstops are still right where they were. Instead of offloading, Boston and Los Angeles chose to stockpile. Yoan Moncada signed with the Red Sox, adding the specter of an infield logjam to their outfield logjam. Hector Olivera signed with the Dodgers, muddling further the confusion on their infield.

If you were to rank all 30 teams by the strength and intelligence of their front office, then by their financial strength, and then blend the two into a single rating, the Cubs, Dodgers, and Red Sox would be the top three teams in the resulting pecking order. That they have assembled the three most interesting, promising, and expensive sets of non-regulars in the league this season feels nothing like coincidence. There’s clearly a reason that they have allocated so many resources to the cause of not only fielding a strong positional corps, but minimizing the talent gap between the players who make up that corps. Here’s what I think they’re thinking, and (more to the point) what I think they ought to be thinking: everyone could stand to play less often.

This isn’t a purely novel concept. Teams carefully regulate the workloads of catchers, and of injury-riddled veterans. They platoon players, matching them up against pitchers who give them a greater chance of succeeding, and resting them against others. Even good, healthy players haven’t always played every day. Still, most players play too much. Instead of aiming to get a player 150 or 155 games per season, teams should (and the Cubs, among others, might be ready to) shoot for 135 games per player, per season.

That’s well-supported by a piece Russell Carleton wrote for Baseball Prospectus nearly two years ago. Carleton’s findings, in brief, in his own words:

“… the number of games that a hitter had played in the previous seven days (or 14 or 21, it all came out significant) had an across-the-board negative effect on all sorts of hits (singles, doubles/triples, and home runs) and increased the number of outs in play that a hitter made. These variables actually had little effect on walks (there was some evidence that hitters walked a little more when tired) and surprisingly, strikeouts.

The difference between a hitter who had played five games in the last seven days (a day off, plus a Monday travel day?) and a hitter who had played in seven games in the last seven days was about three points in OBP. That’s not a lot, but of course, over 600 plate appearances, it’s about an extra two on-base events, and that’s worth a run or so. Over multiple lineup spots, it can build into a lost win really quickly. A manager who does not rotate his players a bit may be bleeding away value and not even realizing it.”

Fresher batters bat better. Fielding is hard—no, impossible—to measure the same way, but it seems a very good bet, an even better bet than the same bet on batters, that fresher fielders field better. Rest is a precious, immensely valuable commodity. I’m not sure that’s ever been in question, but Carleton’s findings help underscore the point. In fact, it would be tempting to wonder why teams don’t rest their regulars much more aggressively, rotate players more, but for two things:

- The difference between the typical everyday player and his replacement tends to be larger than the difference between the rested everyday guy and his tired self; and

- Players want to play every day. They’ve been conditioned to believe that baseball is the lunch pail game, the one you show up and play until you can’t anymore. They see even occasional days off as threats to their status, threats to their stats, and threats to their manhood.

Screw the second point. That’s what these front offices are already saying. Ethier is frustrated at his limited role with the Dodgers, but they made no move to accommodate his request to play every day. Moncada indicated that his favorite position is second base, which means that when he’s ready for the big leagues, he’ll either be forced off of his preferred spot, or encroach upon the playing time of Dustin Pedroia.

The first point has always been the harder hurdle to clear, anyway. Perhaps that’s changing, at least for teams with the smarts and the money to see and address the need for depth. (I don’t want to focus on the Cubs, Dodgers, and Red Sox to the total exclusion of others. Clint Hurdle has hinted that the Pirates have a similar plan, a claim reinforced by their addition of Jung Ho Kang over the winter. The Cardinals have good depth. The Mariners do, too. Each of those organizations has at least some limitation in this regard, though. Nothing limits the Big Three.) La Stella, Alcantara, and Baez don’t provide value of the same shape at second base, but they’re more or less interchangeable, in overall quality. It’s not that hard to see how a fresh Mike Olt could be a better bet against a left-handed starter than a slightly less fresh Anthony Rizzo. If Jorge Soler is totally past the phase of his physical development wherein his hamstrings are balky and prone to pulls, great, but he’s probably not, and in that case, getting even Szczur or Alcantara (or, especially, Bryant) into Soler’s place once a week or so could be an easily worthwhile tradeoff.

Not every day off needs to be a full day off. In the National League, the pitcher bats, and until that blight is removed from the game, there will be ample opportunities for whoever doesn’t start on a given day to pinch-hit. In general, though, lighter duty every now and then is advisable. Players get the rough equivalent of two weeks off over a six-month span each season, and a lot of those days aren’t vacation time; they’re spent on airplanes, getting into hotels at crummy hours.

There’s a limit to the viability of a Kentucky-style platoon system. Ideally, one would craft lineups for lefty and righty starters, and stick with them, encouraging the cohesion that might quicken the turn of a double play or increase the crispness of a relay throw. With pitchers taking up ever more roster space, though, the bodies on hand will never be enough to truly do it, and anyway, teams don’t face right- and left-handed starters with anything like equal frequency. It’s possible not to see a lefty starter for a month. Therefore, the best version of this system doesn’t rely on handedness, and involves simply having bench players as good as your regulars (without unduly sacrificing the quality of the latter group).

I’m about as bullish on the Cubs’ offense as anyone. One reason is that I believe the top tier of hitters they have on hand (specifically, Fowler, Rizzo, Soler, and Bryant) will be really good. Another, though, is that they have a lot of underrated depth pieces. If they use those players aggressively, they might find themselves healthier, more productive, and better prepared for a competitive stretch run than just about any other team in baseball.

Very nicely done. Phase II: an entire article uncovering the way managers like Maddon utilize these deep benches in daily lineup and game situations.

I like the premise of this a lot.

Although, I’m not really sure if the current Cubs lineup has this kind of depth. Rizzo, Soler, Castro, Fowler, and Bryant all seem to be vastly greater than guys like Alcantara, Olt, La Stella, Sczcur, Baez, or Lake. I could see some of the replacement guys stepping up and narrowing that gap, but right now there is a sizable difference.

“It’s not that hard to see how a fresh Mike Olt could be a better bet against a left-handed starter than a slightly less fresh Anthony Rizzo.” Unless Anthony Rizzo completely forgot how to hit left-handed pitching, it’s easy to see how Mike Olt could be far worse.