Photo courtesy of Jerry Lai-USA TODAY Sports

Here are two pitching lines. The first is from 2013, by a rookie relief pitcher for the Chicago Cubs. The second is from this season, by a key lefty contributor for that same franchise:

| IP | K/9 | BB/9 | HR/9 | BABIP | LOB% | GB% | HR/FB | ERA | FIP | WAR |

| 6.2 | 9.45 | 9.45 | 1.35 | .133 | 100.0% | 12.5% | 9.1% | 1.35 | 6.02 | -0.1 |

| 6.2 | 12.15 | 1.35 | 1.35 | .077 | 100.0% | 30.8% | 11.1% | 1.35 | 2.69 | 0.1 |

Because the title sort of gives it away, you’ve probably already guessed that both pitching lines belong to Zac Rosscup, the 27-year-old lefty originally acquired as a peripheral piece when they traded for Matt Garza in 2011. Garza is long gone, but Rosscup remains, having earned the trust of pitching coach Chris Bosio (who sung his praises during spring training) and manager Joe Maddon, who has watched him put up the highest WPA (0.57) of any reliever on the team.

It was, indeed, that same success that led me to Rosscup’s player page. Once I got there, I was struck by a curious consonance between 2013 and 2015: the values for innings pitched, HR/9, LOB%, and ERA were exactly the same. You can already sort of read the story off the numbers: this year to date, and in 2013, Rosscup pitched exactly 6.2 innings, gave up exactly one home run and generally stranded all the runners on base during his time on the mound. This is sort of a momentary curiosity; tonight, for example, Rosscup might throw a particularly ugly inning and throw the symmetry off*.

*Editor’s note: Rosscup already threw off the symmetry by tossing a scoreless, one-hit inning on Sunday afternoon.

It is momentary curiosity, to be sure, but it is still a curiosity. That’s because, despite the similarities, there is one huge difference between the two pitching lines; namely, Rosscup’s FIP, which was an ugly 6.09 two years ago, sits at a pretty good 2.69 today. And we don’t have to look too far to find out which element of Rosscup’s FIP has improved in 2015: it was his BB/9, which sat at 9.45 (!) in 2013, and which has dropped to an excellent 1.35 this year.

Baseball research has a way of leading you down the rabbit hole. Once I’d noticed the similarities between Rosscup’s 2013 and his performance this season, I felt compelled to isolate the difference. I needed to find out why Zac Rosscup might be walking significantly fewer batters than he did two years ago. One answer, of course, might be random variation in a small sample size. We are, after all, talking about a grand total of 13 1/3 innings. But another answer might be that there is something that’s changed in Rosscup’s pitching that allows him to walk fewer batters. And that led me to Brooks Baseball. I wondered, first, what kind of pitches Rosscup had in his tool bag, and how they might have changed between 2013 and 2015.

It turns out that Rosscup is a two-pitch pitcher, using exclusively a four-seamer and a slider. Let’s take a look at his usage rates for those two pitches over the course of his career, and the ratio between his usage of the two pitches (data courtesy of Brooks Baseball, ratios calculated by me).

| Year | Fourseam % | Slider % | Ratio (F/S) |

| 2013 | 74.56 | 25.44 | 2.9 |

| 2014 | 76.98 | 23.02 | 3.3 |

| 2015 | 63.04 | 36.96 | 1.7 |

Well, that’s at least a little bit interesting. For the last two years, Rosscup has gone to his four-seamer about three times as often as he’s reached for his slider; this year, the ratio has dropped well below 2:1 (or, to put it another way, his usage has gone up approximately 50 percent).

Because I am not a Real Baseball Reporter and can’t just ask Rosscup if something’s changed in his slider that has led him to go to it more often, I had to check out his slider velocity to see if there was something there. And there, again, was something that was at least a little bit interesting.

| Year | Fourseam (mph) | Slider (mph) |

| 2013 | 93.36 | 83.73 |

| 2014 | 93.05 | 83.22 |

| 2015 | 93.05 | 86.38 |

The key number, of course, is in the bottom right. That’s the number that indicates that, while his four-seam fastball velocity has stayed constant at approximately 93 mph over the last three years, his slider has jumped from the 83 mph range (for the last two years) to the 86 mph range (this year). Zac Rosscup, now with a faster slider. And lest you think that a 3 mph increase is nothing, consider this: Courtesy of the ever-helpful Harry Pavlidis, the 10/50/90 percentile breakdown for NL slider velocity over the last three years is 80/84/87. This means that Rosscup jumped from somewhere below-average in slider velocity, for the last two years, to somewhere quite a bit above average. That’s meaningful.

Time to take a step back. What have we learned so far? First, we’ve learned that Rosscup, while performing at exactly the same level in terms of results-based statistics between 2013 and 2015, is performing much better in DIPS-based statistics this year than he did two years ago. Specifically, we have learned that Rosscup is walking significantly fewer batters this year than he did two years ago, suggesting that his level of performance this year is more sustainable than it was two years ago. Secondly, and perhaps unrelatedly, we have learned that Rosscup has gained approximately 3 mph on his slider between the two years.

What remains is to explore the possibility, however slight, that these two items are related to one another. In what way might a faster slider allow Rosscup to walk fewer batters? Simplistically, of course, faster pitches are generally speaking harder to hit, which might induce more batters to swing and miss at those pitches. But while Rosscup’s K/9 has indeed increased from 2015 to 2013, it has not increased in an amount equal to the decline in his walk rate. Moreover, while his whiff percentage on the slider has also increased between 2013 and 2015, it actually increased more (6 percentage points) between ‘13 and ‘14 than it did between ‘14 and ‘15 (2.5 percentage points). Since the rise in velocity came between ‘14 and ‘15, I think it’s unlikely this is the entire story.

Rather, I think it’s far more likely that something changed in Rosscup’s sequencing of the slider, and that this change forced batters into counts against which they were far less likely to walk, and far more likely to put the ball in play. To dig into this a little further, let’s go back to Brooks Baseball. I looked around Rosscup’s zone profiles in ‘13 and ‘15 a little bit, and here’s a thing I found:

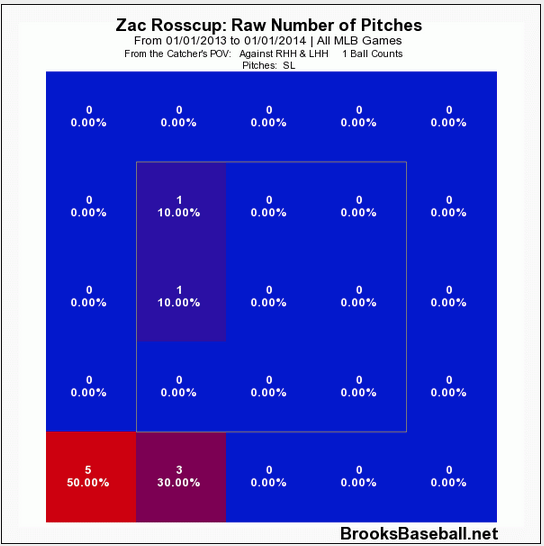

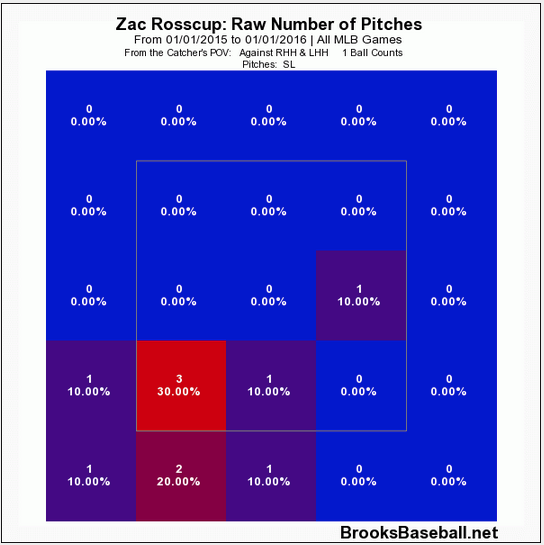

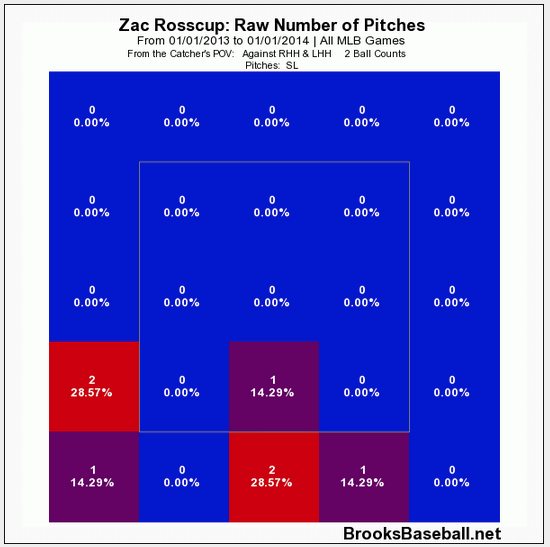

At the top is Rosscup’s 2013 zone profile for the slider on one-ball counts. You’ll notice that he tries really hard to get the ball down, and outside of the zone. On the bottom is that same chart, but for 2015. You’ll notice, immediately, a difference. Rosscup is much more comfortable putting the slider a little closer to the zone. I’m guessing that he figures that the higher speed gives him a little bit of cover if he misses with location, and that allows him to put himself in a position to get a called strike if the batter fails to chase. That means that Rosscup is putting himself in far fewer two-ball counts than he did two years ago. In fact, let’s take a look at those two-ball counts, again with 2013 at the top and 2015 on the bottom:

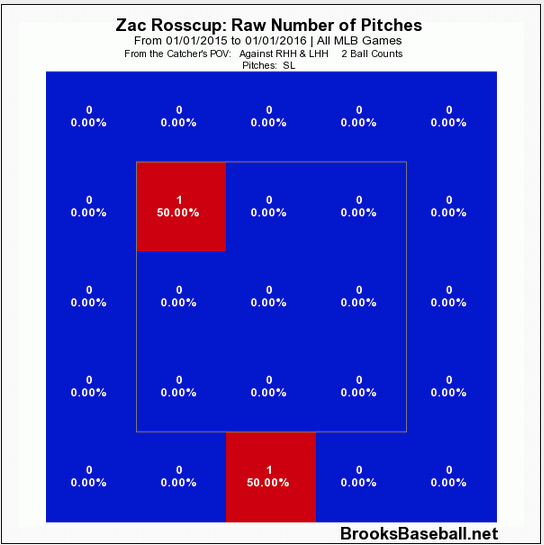

What we’re seeing here is that Rosscup is no longer forced to go to the slider on two-ball counts (thus heading, likely enough, towards another walk). When he does go to the slider on a two-ball count this year, he can put it somewhere near the middle of the zone to try to trick the batter into a called strike, confident that the batter won’t be able to hit it at its new, improved velocity. This, by itself, would tend to lead to fewer walks while having the limited effect on K and whiff rates that we observed earlier.

Maybe there’s nothing here. But then, maybe there is. Maybe Rosscup has been emboldened by his new and faster slider, and has therefore been able to put himself into a position where he walks far fewer batters than he did before. Maybe that means that his 1.35 ERA, once clearly unsustainable, is now a clear indication of his true talent level. If so, that’s indisputably a good thing for the Chicago Cubs. Time will tell.