Photo courtesy of Steve Mitchell-USA TODAY Sports

I think we can all agree that baseball analytics have come a long way. From the discovery of OBP in the pages of Moneyball to all of the complicated math behind DRA—I’m a person that enjoys digging through the numbers to see what kind of stories they tell and to see if that story lines up with my raw perception of the game (it feels so good when it does). The stat revolution has created a bit of a tension between old school and new school, but either way it’s fascinating to see how far we’ve come in the last 15 years when it comes to quantifying the game of baseball. But I’m 34 years old with a second child on the way, and I’m starting to notice I’m developing some “old-man” crotchetyness.

And one of those tendencies is to reminisce about the good-old days of dead-simple stats. One of my favorite stats was to check if a hitter had more walks than strikeouts (MBBTK). This told me a tidy story about the hitter: he had a good eye, could usually control the bat with two strikes, and didn’t like to strike out. While walks have become more and more valued in today’s game, MBBTK isn’t very popular, and that’s because not many players can do it anymore. It has gone the way of the complete game shutout and Sammy Sosa: they’ve disappeared.

And my nostalgic crotchetyness loves things that don’t happen very often. Whether it’s hitting a ball out of Dodger Stadium, laying down a perfectly placed bunt, or pitching with both arms—the fewer people who can do something, the more I’m interested.

Which brings me to the walk: A pretty basic stat that simply tells you how often a player is willing to take four balls and subsequently take his base. While sabermetrics has given much love to the walk (“Three True Outcomes” sounds like a plague from Game of Thrones to me), those walks have come with a whole bunch of baggage—namely strikeouts. As a part of the walk revolution, the strikeout has become more accepted than it once was. Back in my day, the strikeout was equated with the ultimate failure at the plate: you went up there trying to do something and walked back to the dugout with nothing to show for it. The pitcher won and you lost. That’s why so many players got so upset after striking out—which you don’t see as often anymore (unless they’re angry at the umpire).

There are a bunch of new stats that can tell you how often a player swings at pitches outside the strike zone and how good a job a player is doing at swinging at the “right” pitches.

But we already had a stat for that: MBBTK. Players that walk more than they strike out have become increasingly rare over time, and part of the reason is that there isn’t a stigma around the K anymore. And while sabermetrics has determined that sometimes striking out can actually be a good thing (!), the old-school part of me yearns for the players who can pull this very rare feat off.

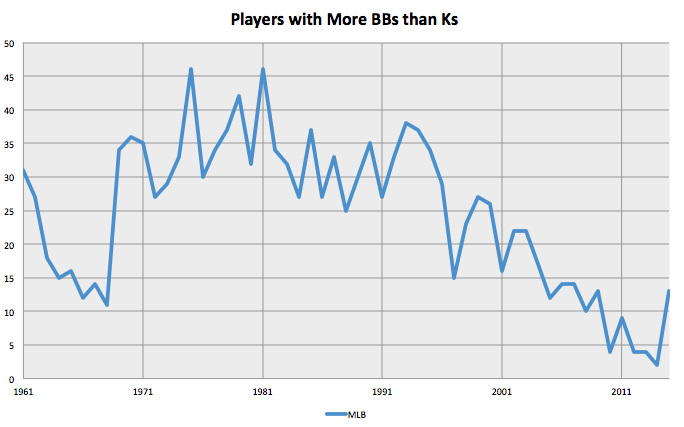

As you can see, it’s a pretty exclusive club. Last year, only Jose Bautista and Victor Martinez managed to pull it off (among qualifying players). This year shows a bit of a spike, but we don’t anticipate all those players keeping up their current pace.

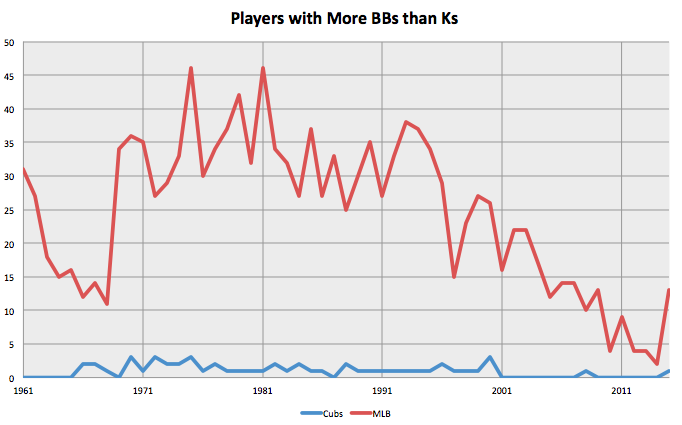

Now let’s take a look at how the Cubs have fared historically at MBBTK:

The blue line? We have Mark Grace to thank for that one (Ricky Gutierrez, Ryan Theriot, Eric Young, and Luis Gonzalez were other recent Cubs to pull it off). For every single year he was in the big leagues (1988–2000), Grace walked more than he struck out. No wonder he was one of my favorite players to watch (the stats match my perception—yay!). If there was a big spot in the game, you wanted him up there more than anyone else, with the exception of the 1998 version of Sammy Sosa, and that’s only if you needed a homerun. Sosa, as you may have guessed, never even came close to showing up on this chart.

Striking out means you failed. Striking out means you went up to the plate and you lost the battle. The pitcher got the best of you. You accomplished… NOTHING. And as a player, I can tell you that there’s nothing worse than trudging back to the plate after a strikeout. There’s nothing you can take from it: you just didn’t get the job done.

Back to the chart—did you notice the Cubs have an MBBTK this year? Anthony Rizzo, he of the already ridiculous season, is pulling it off (28 BBs vs. 25 Ks), which just reinforces how good he’s been this year (he’s never come close to doing this before, not even in the minors).

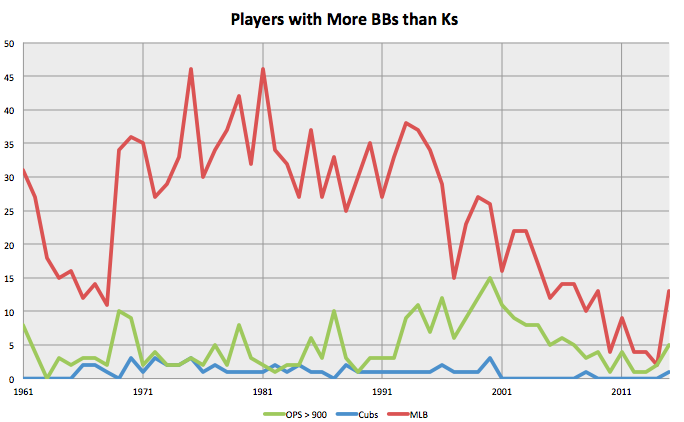

Which brings me to the last chart I want to show you. It adds a third line that depicts how many of these players put up an OPS over .900:

As you can see, MBBTK was way more common in the 70s through the mid-90s, before beginning its steady crash to where we stand today. The OPS line, however, tells us that during the MBBTK heyday, there weren’t a lot of players putting up elite offensive numbers (I’m looking at you, Enzo Hernandez and Eddie Milner). And then came the steroid era in the late 90s and you see that OPS line creep up a bit before eventually succumbing to our current era (the pitcher’s era? low-strike era?). What’s interesting is how the spread between the green line and the red line has shrunk. Players that MBBTK are also putting up an elite OPS.

Rizzo is one of them, and his OPS currently sits at 1.011. So what does all this old-timer nonsense amount to? Rizzo is an elite player. Rizzo is a rare player. The Cubs are lucky to have Rizzo.

You already knew this, but it’s always nice when the old school and the new school back up what you see when you’re watching the games: Rizzo is having an MVP-caliber season—and no one can argue with that.

Numbers were pulled using Baseball Reference’s Play Index.

Just for the record, Branch Rickey wrote about the importance of OBP in Sports Illustrated in the mid-1950’s. Took a while for his ideas to come to fruition!