Position: Second base/Shortstop

2015 Stats: .265/.296/.375, .243 TAv, 1.5 WARP

Year in Review:

After Zack Moser’s profile of Addison Russell on Tuesday, we now turn to the player that Russell ostensibly replaced: Starlin Castro.

The full-season stats you see above aren’t exactly misleading, but it truly was a tale of two seasons for the enigmatic Castro in 2015. It might be more useful to breakdown Castro’s year this way:

Castro Pre-Benching (April 1-August 6): .236/.271/.304, -0.1 WARP (yikes)

Castro Post-Benching (August 11-October 4): .353/.373/.588, 1.6 WARP (wow)

Coming off an injury-shortened All-Star season in 2014 and an offseason filled with mostly-meritless trade rumors, Castro was surely relieved to get 2015 underway. From April until early August, though, he struggled so mightily that it was suddenly unclear whether he belonged on the team at all. He was entrenched as the Cubs’ starting shortstop until August 7th, when (after yet another 0-for-4 game) Joe Maddon made the decision to put Russell at short for the rest of the year and moved Castro into a utility role off the bench.

Castro didn’t play for four days (until August 11th) and didn’t start for a week. When he came back, though, it seemed that something had clicked. Castro picked it up for the remainder of August and then led the team with a 1.065 OPS in September/October. During this time, he quickly re-entrenched himself in the batting order as the primary second baseman. The big question about Castro’s 2015, then, is: what changed?

First, we’ll have to figure out what went wrong in the first half of the year. Many Cubs players went through struggles this year, and for most of them, the struggles stemmed from contact issues. This was not the case for Castro. His contact rate, both inside and outside the zone, was actually about two percent higher in 2015 than it was in 2014.

| YEAR | PITCHES | ZONE_RT | SWING_RT | CONTACT_RT | Z_SWING_RT | O_SWING_RT | Z_CONTACT_RT | O_CONTACT_RT | SW_STRK_RT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2099 | 0.4717 | 0.4655 | 0.7830 | 0.6505 | 0.3003 | 0.8758 | 0.6036 | 0.2170 |

| 2015 | 2096 | 0.4866 | 0.4905 | 0.8025 | 0.6490 | 0.3401 | 0.8943 | 0.6366 | 0.1975 |

The problem for Castro, then, lay in the type of contact he was making. Many posited during the first half of Castro’s season that he seemed to be rolling over balls on the outside of the plate and grounding them to the left side. Below are heatmaps of Castro groundballs from before and after his benching.

Before:

After:

Oh. Well, that looks pretty significant.

These heatmaps show a clear and obvious decrease in groundballs/balls in play for Castro in the second part of his season. Interestingly, this change seemed to be even more dramatic on balls on the inner half of the plate than on balls away. So, we can amend the theory about Castro’s first half struggles just a bit: he was actually rolling over on just about everything.

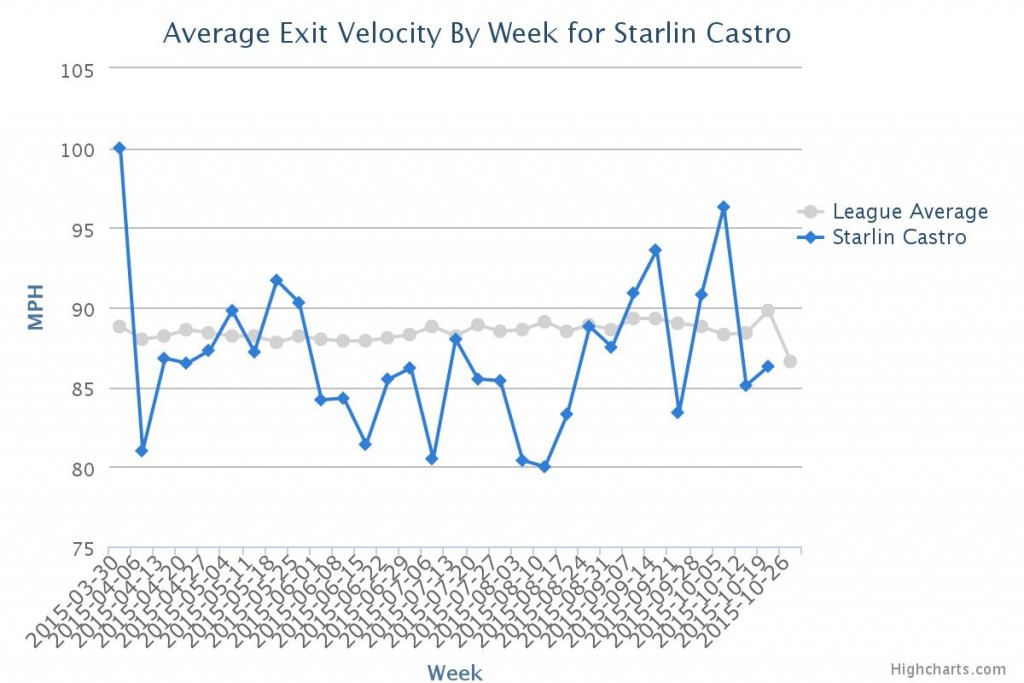

Just to push this point home: Castro’s groundball rate in the first half of the year was 57.2 percent—eight points higher than his career average of 49.5 percent. In the second half, he dropped his groundball rate to 49.1 percent, and in September/October it dropped all the way to 38.9 percent. All those groundouts had to go somewhere, and–not surprisingly–they mostly became line drives. Here, via Baseball Savant, is a graph of Starlin Castro’s weekly exit velocities this season:

As you can see, Castro spent most of the year well below league-average exit velocity, before a spike towards the middle of August. That spike, which lasted for the rest of the season, pushed Castro’s total performance for the season from absolutely terrible to promisingly mediocre. Again, he was worth 1.6 WARP over the last seven weeks of the season–a pace that would put him at 6-plus WARP if he could sustain it for a full year (which is probably a pretty unreasonable request, but just goes to show how good that final run down the stretch was for Castro).

What caused the change? To some extent, we’ll never totally be able to know, and your guess is probably as good as mine. Hitting coach John Mallee might have some idea, though. Something changed pretty dramatically during the week in August when Castro came off the bench–it wasn’t just a case of BABIP luck turning around. Here is a series of pictures (courtesy of Bleacher Nation‘s and BP Wrigleyville’s Brett Taylor) that compare Castro’s early season stance and swing to later in the year:

A series of shots of Starlin Castro from early May (CSN, at home v. Reds). pic.twitter.com/TIAWrK5lq7

— Brett Taylor (@BleacherNation) September 10, 2015

And now a Starlin Castro series from last week, also against the Reds at home, same camera placement. Some changes. pic.twitter.com/IoSO6vBKHg

— Brett Taylor (@BleacherNation) September 10, 2015

From these images, it seems that Castro closed his stance and shortened his leg kick a bit as the season went on. The swing looks more compact, too, but that could have something to do with the different pitch location in the different images. Perhaps these adjustments, though, were what Castro worked on, and perhaps this is what allowed him to contribute so much more down the stretch. Look at the pitch trax location of this NLDS homer. It is a slider in the exact location that Castro was seen as routinely rolling over on in the first half:

While Castro’s offensive season was marred with inconsistency, his defense was actually consistently excellent this year. He put up 5.1 Fielding Runs Above Average, which was good enough for sixth-best among all qualified shortstops and fourth-best among all qualified second basemen. Much-maligned for his occasional mental lapses in the early part of his career, Castro has become a very good/great fielder at two premium infield positions. This is what makes him so frustrating and so promising at the same time. He doesn’t have to hit great to be an All-Star caliber player. He just has to be consistently good.

Looking Ahead:

If the big question for Castro’s 2015 was “what changed?”, then the big question going into 2016 will be “is this change sustainable?” We don’t know, of course. Castro, heading into his age-26 season, is just as unpredictable and enigmatic as ever. If he made a mechanical change in August of this year, we can hope that he will bring it into next year. The player we saw down the stretch has so much promise and upside; a full season of “good Castro” has an enormous amount of value. But Cubs fans also hoped that he would bring his 2014 production into 2015, and that didn’t happen.

Castro’s inconsistency makes it extremely hard to project how the Cubs will treat him this offseason. Keeping him is risky. The four seasons and 41 million dollars remaining on his contract could once again look extremely expensive if he struggles to start the season–this could be a high point in his value. Trade talks will undoubtedly be more meritorious than they were last offseason. Castro might be more valuable to another team as a shortstop than to the Cubs as a second baseman. The Cubs young(er) infielders–Russell and Javier Baez–both showed that they are likely to stick in the league as starters, and the Cubs still have Tommy La Stella as a viable backup as well.

The only thing riskier than keeping Castro might be trading him, though. If he plays anything like the way he played the last two months of the season, the Cubs would be trading a cost-controlled, multiple-position, All-Star infielder who is entering his prime. Castro happily adjusted to playing second base, and if all goes well, I could see him manning that position excellently for the foreseeable future. Castro might also be especially valuable in the Cubs’ lineup specifically: he is a contact hitter in a lineup full of strikeout-happy sluggers. This alone might be enough to argue for trading Baez instead of Castro.

The front office, then, will be taking a risk with Castro no matter what they decide to do. Luckily, the Cubs brass has a lot of experience taking calculated risks. I can certainly see both sides of the argument, and at this point very few results would surprise me. On the whole, though, I’d expect to see the Cubs’ longest-tenured player report to Spring Training next year as the Cubs projected starting second baseman–Hoverboard Segway and all. A season full of ringing line drives or stinging disappointment could follow. At this point, it’s really anybody’s guess.

Lead photo courtesy of Jerry Lai-USA TODAY Sports

People forget that through May, Castro was pretty good at the plate. It was June-early August that was terrible. Did you notice anything in the transition from May to June?

Even though he was hitting the ball harder in May, Castro actually had better results in June (he hit .221 in May as opposed to .245). This is likely a BABIP issue in a small sample size, but it does show that Castro had some bad luck early in the year before his prolonged slump. You’re right that the *really* bad part of his year only lasted two months or so.

I didn’t notice anything specific in the transition from May to June, but I will say that the inflated groundball rate was present right from the start of April. This suggests that the underlying problem (whatever it was) might have been there the whole time.

Thanks for reading!

It was actually only the first 3-4 weeks of April, to the point where there were blogs posts of “Castro putting up MVP type numbers so far”.

–

Anywho, I don’t see why an opposing pitcher would EVER throw him a pitch on the inner half. Keep the ball outside half, or even a little off the outside corner, and Castro will keep hitting weak grounders.

The idea that Castro had a good April is a bit misleading. Sure, he hit .325 for the month, and that’s certainly encouraging since we know that much of Castro’s worth comes from his ability to put the ball in play and hopefully survive off a high batting average. However, the peripherals showed that what he did in April wasn’t much better than what we saw the rest of the season outside of Sept/Oct. Right off the bat, we see that he had a meager ISO of .085, meaning he was just singling the hell out of the ball. Perfectly fine for certain hitters, but he put up three extra-base hits for the month and even those singles were pretty lucky as I’ll show.

It was encouraging to see Castro get off to the ‘nice’ start in the hopes that perhaps it would lead to more solid, hard contact, but the fact is the writing was on the wall for what we saw the majority of the summer months from him. April was his highest month for GB% (64.3%!!), infield-hit rate (a ridiculously unsustainable 15.6%, especially for a 50-ish runner like Castro. Speedsters like Dee Gordon, Mike Trout, and Billy Burns didn’t even post those types of numbers for the season), and soft-hit percentage (30%). It was also his lowest month for hard-hit rate (15.6%), so clearly things were a little lucky for Castro. For him to be good, he needs a little luck, for sure. But April was almost *all* luck for him. Sept/Oct was completely different: 13 XBHs, 28.8% hard-hit rate, and 38.9% GB rate. So to suggest April was good ignores that fact that it was heavily reliant on luck. Yes, Castro does needs some luck, he needs a strong BABIP because he’s not going to take many walks. But he also needs to hit some doubles and knock the ball out of the park occasionally, hit liners over grounders (though the seeing-eye singles are a part of his game, hence luck being important), and just generally go with pitches, instead of just rolling everything over to the shortstop. The difference between April Castro and Sept/Oct Castro is significant.

What I saw at the end of the year was a sharp increase in TWTW. Any numbers that can back that up?