The first time I went to Wrigley Field was in April of 2003. It was cold. Quite cold, in fact, but the atmosphere was not. Fans were relaxed—warmed up by cold beer—and I got to see Kerry Wood strike out 13 Pirates in a 4-0 shutout. We were newcomers to the party, but the instant feeling of belonging, the overwhelming sense of history, and the beauty of the ballpark and surrounds made for an exceedingly pleasant experience. We sang after the final pitch that day, but I would have been hooked regardless.

I have known ever since that Wrigley is a powerful place. We left Illinois seven years ago, but the memories of afternoons spent there still surface when so many others have faded. I’ll be honest: I had to look up that box score. I didn’t recall the outcome, but I remembered the feeling. For many, myself included, Wrigley’s appeal extends well beyond its function. As every Cubs fan understands too well, players may have disappointed at times, but the home field never did. Now, on the cusp of a new season of hope, I want to know if the Friendly Confines’ magnetism has actually been part of the problem all along.

George Will elegantly described Wrigley as a venue that transcends the game:

“People go to museums of fine art to see the paintings, not the frames that display them…Many people do, however, decide to go to Chicago Cubs games because they are played within this lovely frame…Wrigley Field is lovelier than the baseball often played on the field…the ballpark is part cause and part symptom of the Cubs’ dysfunctional performance.”1

He pointed to the club’s original business model, from P.K. Wrigley himself, as the culprit. With a focus on maximizing ticket sales above all, marketing was centered on the beauty of the field, the relaxation gained from a day at the park, the socializing and the beer. Improvements were made to the venue instead of the roster, with success measured by fan contentment rather than actual winning. Fans were basically sold the message that the score didn’t matter, and, for a long time, they bought it.

The pop economics text, Scorecasting—think Freakonomics for sports—attempted to quantify this unique relationship of illogically loyal fans and a losing franchise.2 Based on a century of baseball attendance, the Cubs were dubbed “America’s Teflon team,” its fans scoring the lowest sensitivity to winning compared with any other club. This measure (also called attendance elasticity to winning) was 0.6 for the Cubs, compared to 1.0 for the league. An elasticity of 1.0 means that winning and attendance percentages tend to move up or down together, one for one. Above one means fans are more sensitive to winning, below one means they are less so.

And so Will’s argument, and its quantification in Scorecasting, supports an argument: that Cubs ownership has responded to the perverse incentives created by the low elasticity, and focused more on promoting the Cubs’ “lovable losers” reputation than on winning, which often requires up-front money, and always requires investment. The argument runs, in short, that if fans were properly incentivizing team decision-makers all along, or if decision-makers were more willing to challenge fan expectations, the most infamous losing streak in sports might never have been.

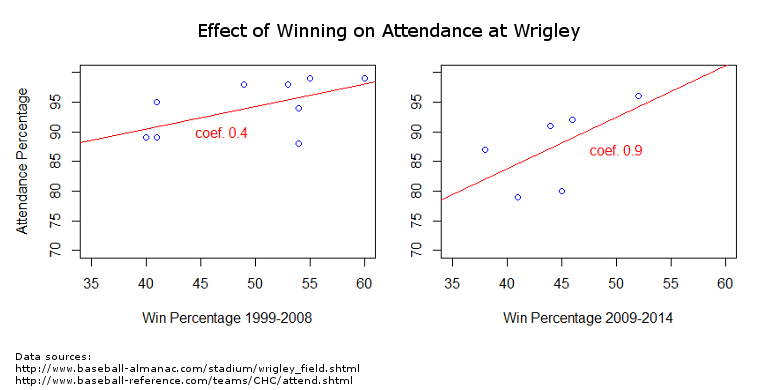

But that narrative doesn’t feel like it adds up any more. It may help explain the first nine decades of losing at Wrigley, but doesn’t feel like it fits for the fans or management of today. The Scorecasting data ended in 2009, and of course Will wrote far earlier than that. Home games with shockingly empty seating in the disappointing seasons of 2013 and 2014 suggested that some fans were beginning to lose the faith. Attendance had dropped 20 percent from a decade earlier near full capacity, and I was curious if the Teflon analogy would hold up. A couple linear regressions later, I had this:

Despite the admittedly small sample size, I still find the results here interesting, because they fly in the face of that earlier narrative. The plot on the left reflects attendance during the 10 years prior to the Ricketts family’s 2009 acquisition of the team. Regarding the purchase, Tom Ricketts was quoted as saying, “They sell every ticket, every game, win or lose.” Pretty accurate at the time. But it is not the situation he ended up with, evidenced by the plot (or plight?) on the right. Contemporary fans have seemingly had enough. Winning matters to them, so it must matter to Ricketts.

I think, though, that’s probably a chicken-or-egg statement. Let’s try this instead: Winning matters to Ricketts, so it must matter to fans. Ironically, the change in ownership, and the new attitude and business model it brought to the North Side, probably best explains the fans’ new behavior. When he took control Ricketts promised, “Everyone needs to know we are here for the long term and we are here to win.” He got Epstein. He got Maddon. He embarked on a $500+ million renovation of Wrigley Field, to elevate it to the modern standards of professional baseball (video boards, huge advertising contracts, and all). Regarding the improvements to Wrigley, he also stated, “We can’t mess with that special feeling.” But that’s just not realistic. They did mess with it, and, apologies to the diehards, it needed to be done.

Ownership’s signals have clearly changed. Fans are no longer being invited to a park, happy hour, or museum for a pleasant (and expensive) afternoon. Their expectations are focused on seeing professional, competitive baseball, because that’s the message that dedicated leadership and a modern venue projects. This explains why many stayed home when the play just wasn’t competitive in recent years. The Cubs were selling something new and different, and not able to deliver.

In exactly the way this business is supposed to go, fans spoke and ownership responded. The Cubs came out swinging with back to back huge payroll bumps in 2015 and 2016. Now enjoying one of the best pre-season positions in baseball with offense, pitching, versatility and a manager to piece it all together, the Cubs are undoubtedly doing all they can to optimize performance. Attendance is not going to be a concern. If high expectations can indeed breed success, a hat tip may be due to the once Wrigley Faithful who stayed home and voted to finally get this thing done.

None of this is to say the “special feeling” of Wrigley is gone, or even diminished. It just means that priorities there are less perverse than they might have been in the past. This season at the Friendly Confines, one hundred years after the Cub’s home field debut, ticketholders may have it all at last. With any luck, the picture will turn out even prettier than the frame. And it’s a spectacular frame.

1George F. Will, A Nice Little Place on the North Side (New York: Crown Archetype, 2014), 13-14.

2Tobias J. Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim, Scorecasting (New York: Crown Archetype, 2001), 243-247.

Lead photo courtesy Matt Marton—USA Today Sports.

Love it!