When the Cubs acquired Miguel Montero in December 2014, I was higher on the move than most. I had even written an article encouraging precisely that course of action, a few weeks beforehand. I pointed to Montero’s phenomenal numbers as a pitch framer, but also to the fact that the Diamondbacks had overused him, contributing (I felt) to his two seasons of cratering offensive output. I looked at Montero and saw a player with plate discipline and power, who simply hadn’t been able to sustain and express those characteristics in the face of very heavy use at the game’s most demanding position, and in the face of injuries. On a Joe Maddon-led team, I predicted, Montero would rest more, face left-handed pitchers (against whom he was notably helpless) less, and thrive.

I was kind of right. Montero did have a bounceback season with the Cubs. He didn’t match the All-Star-level production he had achieved in his prime (a .284 TAv in 2011, .296 in 2012), but he far outpaced those brutal, injury-fraught and overworked years that followed (.240 and .260 TAvs in 2013 and 2014). He finished not only with the best framing numbers of his career, but with a .279 TAv in 403 plate appearances. He was almost a four-win player, despite missing three weeks with a thumb injury, and despite David Ross starting whenever Jon Lester pitched, and despite Welington Castillo and Kyle Schwarber grabbing a few starts from him at the beginning and end of the season, respectively.

While I have no doubt that Montero benefited from more rest and increased platoon protection, though, that turns out not to be the real reason for his offensive renaissance. He did face right-handers in 86 percent of his plate appearances, up from an average of 76 percent over his six previous seasons as a regular, but he also posted the highest ISO, highest walk rate, and lowest strikeout rate of his career against lefties, for seasons in which he had any significant sample against them. And he did appear to wear down, first in the stretch leading up to the injury that gave him time off, and then at the very end of the season, including the playoffs. For a 31-year-old catcher of his size and with his mileage, it’s utterly unsurprising that he would battle some accumulative fatigue, and the argument for resting him more was that doing so might minimize the extent of that, not eliminate it altogether.

Still, the biggest and most compelling reason Montero had a strong offensive season was not because he was protected from anything. It was, indeed, nothing I foresaw. It was something better. Montero went to work with John Mallee and Eric Hinske, and remembered how to hit like a badass.

Here are Montero’s stats for the last five years, broken down by where he hit the ball. This data is from FanGraphs:

Miguel Montero, Pulled Batted Balls, 2011-2015

| Season | Pulled Batted Balls | AVG | SLG |

| 2011 | 173 | .366 | .674 |

| 2012 | 134 | .336 | .575 |

| 2013 | 128 | .328 | .552 |

| 2014 | 156 | .269 | .462 |

| 2015 | 92 | .308 | .473 |

A disclaimer, off the bat (HA!): It seems like he pulled the ball significantly less often in 2015. Remember, though, he played less often in 2015 than he had in several years. He also struck out and walked more, so know that as a percentage of his total batted balls, Montero actually changed relatively little in terms of the frequency with which he hit to each field. He had become pretty pull-happy over his two previous seasons, but the correction to that in 2015 was fairly small.

Focusing on the results, okay, a small rebound from the miserable dropoff he’d suffered in 2014, but he was still down significantly from his peak. It certainly wasn’t the ability to pull the ball with authority that restored Montero’s offensive status.

Miguel Montero, Batted Balls to Center Field, 2011-2015

| Season | Batted Balls | AVG | SLG |

| 2011 | 134 | .318 | .470 |

| 2012 | 128 | .531 | .789 |

| 2013 | 94 | .341 | .440 |

| 2014 | 130 | .320 | .416 |

| 2015 | 94 | .402 | .587 |

Now we’re starting to see something. The .400-plus batting average has something to do with BABIP luck, you can bet, but look at the power outage he’d suffered in 2013 and 2014 when he went up the middle. Compared to that, 2015 was a really strong showing. Montero found a way to really drive the ball to center field. That’s nothing, though.

Miguel Montero, Batted Balls to Opposite Field, 2011-2015

| Season | Batted Balls | AVG | SLG |

| 2011 | 94 | .370 | .576 |

| 2012 | 96 | .277 | .372 |

| 2013 | 87 | .264 | .379 |

| 2014 | 112 | .333 | .514 |

| 2015 | 61 | .344 | .738 |

That slugging average is not a misprint. Montero launched seven opposite-field home runs in 2015, one fewer than in the four previous seasons combined, and he did it on far fewer batted balls than in any of those four. He simply started killing the ball to left field.

How? That answer turns out to be twofold, as any good change in offensive output must be. There was a mechanical element, and an approach element. I suspect that the former fed the latter, so let’s start with the mechanics.

Here is a Montero swing from June 2014, in Colorado:

I am not a scout, and I bet you are not a scout, but come on, let’s play scout. Montero sets up in a slightly open stance, knees bent, hands somewhat away from the body and a little below his ear. He mostly stands still as he waits for the pitch, other than some hand and wrist movement and a slight bob of the bat, just trying to have the lumber moving on time. As Jordan Lyles’ hands break and his arm trails back, Montero strides, coiling his front hip by striding into a more closed stance. His upper body’s answer to that is a cocking of the back elbow, a slight counterrotation of the front shoulder, and then a sweep. His bat takes a long time to significantly change its angle with respect to the ground, and then, as he spins through, it sweeps up and through the hitting zone, with just a very slight dip of the back shoulder. He’s a little off the sweet spot, though, and flies out lazily to center field. (The runner scores from third, though, so that’s some consolation.)

Now, here’s Montero at Miller Park in 2015. (Was it Mother’s Day? You decide!)

It doesn’t even take clicking on and activating the video to see the first set of differences. Montero stands more straight here, is slightly more closed, though still open. His hands are a little farther from his body, though only a very little, and they’re lower. His bat is more upright.

As Matt Garza begins his delivery, Montero’s movement starts. His bat is waggling a little more, the barrel tipping very slightly toward the pitcher. His front leg bends very slightly, flexes, really, comes back to its original position. He briefly gets up onto his toes on that lead foot. Then, at right about the moment at which he started his stride in 2014, Montero shifts his weight back to neutral, and quickly taps his back foot. (Thanks to swing guru and hitting insight fountain Ryan Parker for helping me see this. Ryan also noted that Nolan Arenado does the same thing.) Now his lower body is building more momentum, and yet, his hips are less set. As he strides, he’s able to achieve a deeper hip coil. There’s a point where his right heel is pointing somewhere not far off Garza’s left shoulder, meaning he’s turning that hip much more away from the mound. That coil helps drive the momentum of the swing, as does the back-foot tap, because it keeps him from getting stuck at all on the back side, in terms of balance. Everything’s flowing, and everything is moving fast. That bat waggle has his hands in better position to time his barrel to the ball, and because he’s swinging harder and faster, he can trust that to create damage, so his shoulders stay better in line and his bat takes a flatter plane through the middle of the zone.

He made contact when his bat was at, perhaps, its top rotational speed. He hit the daylights out of this baseball, just thrashed it, into the bullpen in left-center field. It was gone when it left the bat. Matt Garza was mad. Both pitches I just showed you were 92.2 MPH first-pitch four-seam fastballs, and they were thrown by similar pitchers in hitter’s parks. The second one was actually a little further toward the outside corner, but the locations were very similar. The difference in results speaks to the difference in the effectiveness of Montero’s mechanics. The more balanced, freer swing he developed in 2015 allowed him not to worry about being a little later into the hitting zone, because he also passed through that zone faster. That meant driving the ball to all fields, and having an especially increased ability to thump it to left and center.

These swing adjustments—increasing torque and bat speed, standing straighter, carrying the barrel of the bat to the ball on a more level plane—helped Montero almost stop popping the ball up altogether. He did so on just 3.2 percent of all his batted balls, easily the lowest rate of his career. He hit line drives on 29.6 percent of all batted balls, easily the highest rate of his career. The changes seem to have been perfect for Montero, whose compact build encourages just that kind of explosion into the ball. John Mallee did a wonderful job helping Montero find the right tic to unlock his ability to drive the ball the other way, and to give his swing more fluidity, more violence, and more swagger.

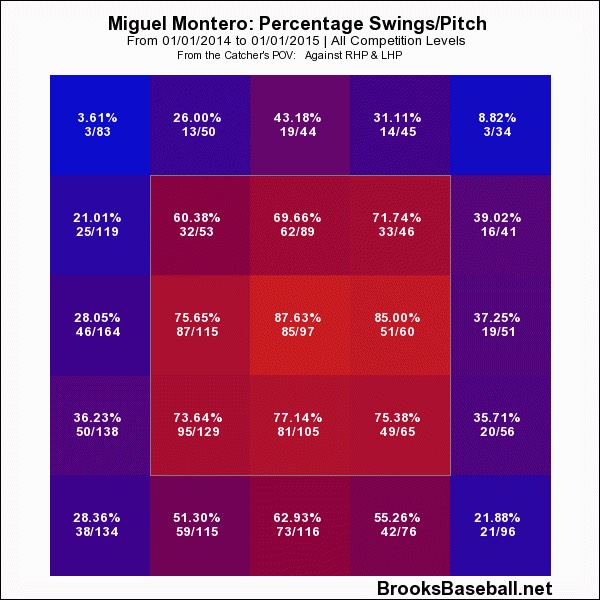

In order to really work, though, that new swing needed to be paired with a new approach. As I mentioned earlier, Montero became fairly pull-conscious in the poor seasons prior to 2015. Here’s a Brooks Baseball breakdown of his swing tendencies in 2014.

A pull hitter has to be looking for pitches they can pull, especially pitches they can pull in the air, and be aggressive when they get one. Montero certainly did that, hacking away at anything on the inner half, and most things above his belt.

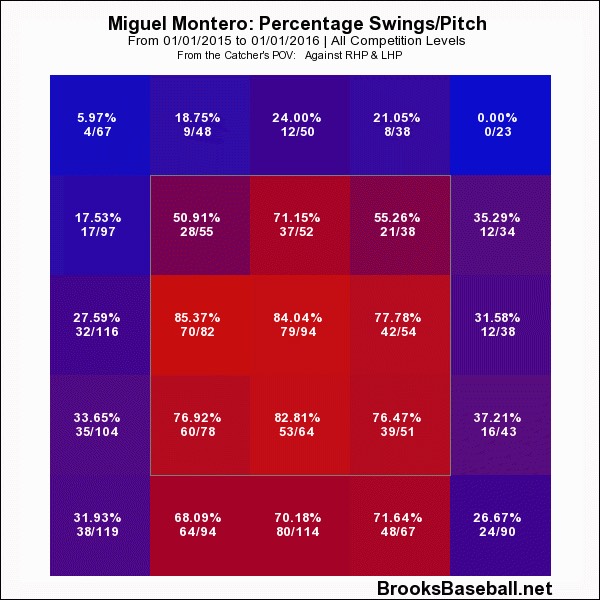

A hitter who can reliably drive the ball up the middle and to the opposite field, though, doesn’t need to be as focused on waiting for elevated pitches, and certainly shouldn’t be sitting on something inside. In 2015, Montero was that kind of all-fields-with-authority hitter, and he approached his at-bats that way.

Last summer, Andrew Felper wrote nicely about Montero’s rediscovery of his ability to mash sinkers. Part of that was his renewed commitment to swinging less often at pitches up, and more often at pitches down, where his swing (the old one and the new) could better handle them. Maybe more notably, though, look at the middle boxes of the zone. Montero basically flipped his strike zone inside out. He was aggressive any time pitchers came after him in the zone, to be sure, but in 2015, he switched from looking for pitches in and up, and instead, looked for anything over the outer half of the plate.

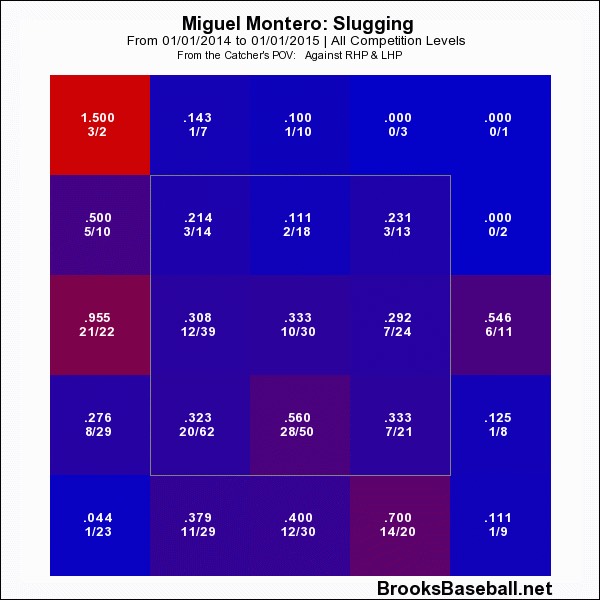

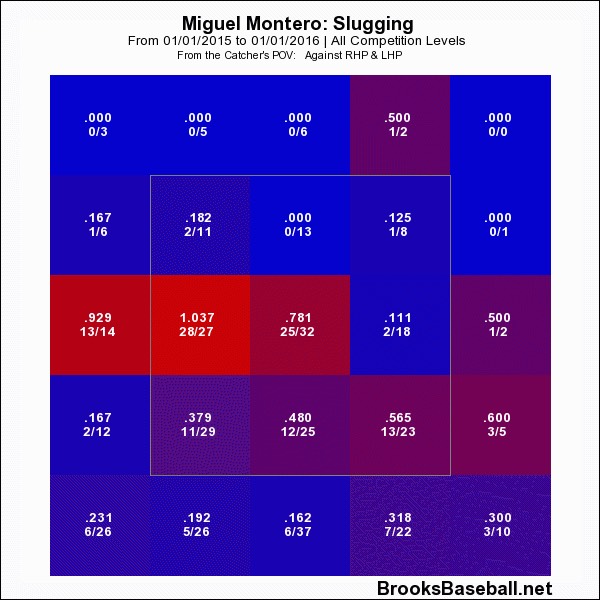

To highlight the efficacy of his approach change, here are Montero’s slugging averages by pitch locations for both seasons.

Those two blazing red boxes at the far left of the 2015 graphic should startle you. They startled me. I tried to look up whether anyone was better on such pitches. Baseball Savant breaks up the strike zone a bit differently, but I ran a search for left-handed batters with at least 50 balls in play on pitches either over the outer third of the plate and in the middle of the zone vertically, or out of the zone away and from the belt up. (That would include Montero’s hot zones, but also ones above it off the outside corner, where he had no success.) No one was better. Montero slugged .830 on those pitches. Mark Teixeira was second, slugging .800. Bryce Harper (admittedly, in over twice as many batted balls, making his figure the more staggering one) slugged .769. A new, improved setup and swing allowed Montero to look for different kinds of pitches, and to do thoroughly impressive things with them when he got what he was looking for.

It’s not all this simple, of course. Batting low in the order (sometimes right in front of the pitcher), Montero saw fewer pitches in the strike zone than ever before. Even so, and perhaps because of the confidence he gleaned from his new, more powerful swing, he swung more often than he had in years, preferring to do damage with the first good pitch he saw than to wade into deep counts and take his chances with two strikes. It’s by no means promised that the changes Montero made in 2015 are physically or statistically sustainable. The league might not have had time to adjust its book on him, or might simply have been too slow to do so. Montero might not be able to stay healthy while bearing both the workload of a starting catcher and the added strain of a more violent swing, one that asks more of his hips and core, especially. A lot of things could turn the carriage back into a pumpkin, but if Montero can maintain the changes he made to both the physical and mental aspects of his offensive game in 2015, he’s going to be a huge part of the Cubs’ offense.

Lead photo courtesy Matt Kartozian—USA Today Sports.

It’s a pleasure to read such well-thought out analysis.

At other Cubs sites I frequent, there’s a frenzy to see Willson Contreras starting next year, but assuming not too much changes with the Cubs’ composition or Montero’s performance, I can’t imagine Montero not getting in his usual 3-of-5 starts with with the Cubs’ World Series window looking to extend the next two seasons, at least for now.

Also, since it’s a catching article, David Ross! Anger! Sorry, can’t resist.