Last Monday, January 16th, the World Series Champion (because it never gets old) Chicago Cubs donned their finest apparel and headed to the White House to meet President Obama. Nestled amongst the many jokes between Chicago comedians Theo Epstein and Barack Obama, the former offered the latter a gateway into Cubs fandom in the form of a lifetime pass to Wrigley Field. A dedicated White Sox fan, Obama is not likely to act on this gift or fully appreciate his Midnight Pardon, but he can (if he picks up a footnoted book or reads this article) revere in the deep relationship the presidency has with the Chicago Cubs. Although, according to Theo, the last time the Cubs visited the White House was in 1888 under the presidency of Grover Cleveland, the 1920 Cubs also found themselves particularly close to the office, but for a much different reason.

The Cubs’ Principal Owner, Albert Lasker, was an advertising mogul in charge of marketing Republican presidential nominee Warren G Harding to the country. During the initial months of his campaign, Harding was advertised partially based on his hobbies, namely golf. However, golf was viewed as both an elitist sport and one that was not very manly. As advertisements with clips of him golfing circulated through movie theatres across the country, his popularity decreased, and the RNC grew concerned they could lose the election. Lasker frantically searched for a solution to Harding’s perceived elitism and finally decided he must exploit the connection between the nominee and America’s sport, baseball. However, the long-standing tradition of politicians as spectators at baseball games forced Lasker to up the ante by having the 55-year-old Harding actually appear in a game.

As the Cubs were in the midst of a sub-.500 season and had no chance of making the playoffs, Lasker and Wrigley Jr., both ardent Harding supporters, devised a plan to have the Cubs play an exhibition game in Harding’s hometown, Marion, Ohio, against the local semi-pro Kerrigan Tailors. Harding had played one season with the Tailors as a teenager and held a stake in the team, prompting locals to refer to him as the team’s biggest fan. In order to make the game seem less manufactured, Lasker marketed it as being the brainchild of Wrigley Jr., who had the idea after having a conversation with Harding in which the nominee lamented the loss of his playing days. After several professional teams (the Yankees, Reds, and Indians) refused to play in the game due to its political nature, Lasker and Wrigley Jr. settled on the Kerrigan Tailors, billing it as Harding’s hometown demonstrating its love for the most ardent supporter of the Tailors. Lasker wanted it to seem like “the game should ostensibly be paid for by the citizens of Marion” as they embraced Harding’s love for the game.[1]

Although it is likely several owners saw through this veiled orchestration, they could not call for an investigation as they no longer oversaw baseball operations. Following the 1919 Black Sox scandal, Lasker grew worried that corruption would destroy the MLB, so he lobbied for the creation of a single commissioner who would oversee all baseball matters, primarily those concerning corruption. The AL and NL representatives agreed this position should be filled by somebody not associated with the league, enabling Lasker to appoint his friend, federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (who has absolutely one of my top-5 favorite names).[2] Thus, as a reward for his attention to corruption, Lasker received a free pass to commit some of his own.

Taking place on September 2nd, 1920, in Lincoln Park, the game drew roughly 5,000 fans, 70 of whom were movie stars invited by Lasker, in hope of portraying Harding as an everyman people relate to and admire, like Anthony Rizzo surrounded by Kris Bryant as the movie stars. Prior to the game, Harding, outfitted in white trousers, a blue sport coat, and his everyman straw hat, mingled with the fans and signed autographs for the Cubs, trying to convey the idea that he is “just like every other real American” in his voracious attachment to baseball. After greeting both teams and throwing several warmup pitches, which definitely weren’t for show, Harding took the mound to what the Marion Star described as an enthusiastic crowd “equal to any world’s series.”[3]

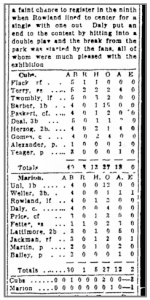

Harding opened the game with three pitches. The first two were “a tad” outside, forcing Harding to throw a third one, which would likely be a strike as the third “is usually a strike with all pitchers after the first two are balls.”[4] Whether the batter took customarily horrible swings or was too baffled by Harding’s technique (described as “shooting the ball to his receiver [the catcher]”), he missed Harding’s third and final pitch by about a foot. The presidential candidate then left the game to massive applause and was replaced by Cubs Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland “Old Pete” Alexander, who retired the three batters in short order. The Tailors also held the Cubs scoreless to start the game (partially because the Cubs loaned them several pitchers to make the game fairer), but the Cubs managed to score one run in the third and added two more in the seventh to win 3-1 over the local Ohio team. Regardless of this final score, the crowd thoroughly enjoyed the game, impressed with the home team’s effort and enamored with Harding’s new image.

Harding opened the game with three pitches. The first two were “a tad” outside, forcing Harding to throw a third one, which would likely be a strike as the third “is usually a strike with all pitchers after the first two are balls.”[4] Whether the batter took customarily horrible swings or was too baffled by Harding’s technique (described as “shooting the ball to his receiver [the catcher]”), he missed Harding’s third and final pitch by about a foot. The presidential candidate then left the game to massive applause and was replaced by Cubs Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland “Old Pete” Alexander, who retired the three batters in short order. The Tailors also held the Cubs scoreless to start the game (partially because the Cubs loaned them several pitchers to make the game fairer), but the Cubs managed to score one run in the third and added two more in the seventh to win 3-1 over the local Ohio team. Regardless of this final score, the crowd thoroughly enjoyed the game, impressed with the home team’s effort and enamored with Harding’s new image.

In addition to demonstrating his pitching prowess, Harding let loose his baseball knowledge to reporters on his way to the dugout after pitching. In front of a gaggle of reporters and cameramen, Harding proceeded to self-endorse with a series of baseball metaphors that would spell the death of any serious reporter’s career:

“You can’t win a ballgame with a one-man team. I am opposing one-man play for the nation. The national team now playing for the United States played loosely, and muffed disappointingly, the more domestic affairs and then struck out at Paris [the Treaty of Versailles]. The contending team tried a squeeze play, and expected to secure six to one against the United States. But the American Senate was ready with the ball at the plate, and we are still flying our pennant which we won at home and held respected against the world! Hail to the team play of America!”[5]

Harding blasted then-current president Woodrow Wilson for abandoning domestic affairs in favor of failed international schemes, and he warned against Democratic nominee James M. Cox’s promise to follow Wilson’s example. Lasker quickly turned this film into a series of advertisements that painted Harding as a regular American participating in regular American activities. In the days following the exhibition game, newspapers across the country lauded Harding the baseball player, and many ran stories declaring him the clear winner based on his “wholesome unaffectedness and modest sincerity…[and] his fervent reverence for his country.”[6] Voters flocked to him, and reporters increasingly questioned him about baseball, framing him as the candidate most concerned with “Americanism.” Behind this late rebranding, Harding won the presidency in a landslide, garnering 64% of the popular vote and 404 electoral college votes.

This rebranding followed Harding throughout his short presidency. He frequented baseball games with his wife, both of whom had long supported the Cincinnati Reds, and threw out the first pitch twice. On the day of his death, all baseball games were suspended so players and fans alike could mourn the man who became a beloved baseball figure. Just before Harding’s death, biographer Arthur Wallace Dunn summarized his appearance in the exhibition game as such: “The President ceased to be a ball player the year he was elected to be President. He played first base in a charity game at Marion and retired after one finger had been bunged up by a thrown ball, and with a batting average of 1,000.”[7] Coincidentally, when outright backing a presidential nominee, the Cubs have also batted 1.000.

Lead photo courtesy David Banks—USA Today Sports

[1]John A. Morello, “Selling the President, 1920: Albert D. Lasker, advertising, and the election of Warren G. Harding,” Vol. 1920. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, 54-58.

[2] http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/mlb_history_people.jsp?story=com

[3] Fred L Kraner, Marion Star, September 3rd, 1920.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Morello, 57.

[6] New York Tribune, September 3rd, 1920

[7] Arthur Wallace Dunn, “From Harrison to Harding: A personal narrative, covering a third of a century,” (New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1922), 219-220.

GREAT article. thanks very much for this.

I do take exception that you termed this “corruption.” From an image standpoint it’s not like they were trying to sell Harding as something he wasn’t. He actually WAS a ballplayer.

There didn’t seem to be any rules against an exhibition game and I’m assuming the players on both sides got paid. It certainly is inventive and i doubt any major sports team could hold an exhibition game centered around a political figure but all politicians try to associate themselves with a winning team. (Remember Hillary claiming she grew up a Yankees fan when running for NY Senate?)

Is it any worse for a private owner like Jeff Bezos to skew his editorials and use his for profit company to help elect Hillary?

So I wouldn’t say “corrupt.” For me it would just be distasteful.