There has always existed an immense difficulty in portraying great men, in boiling them down to several quotes or anecdotes that get misplaced and misrepresented through time. It is perhaps even more difficult to capture the lives of good men, who exist in subtler forms transferred from person to person in hidden conversations and the moments between camera flashes. It becomes useful, then, to turn to literature to uncover the beauty and truth that exist in the seemingly mundane lives of these individuals, to both track the threads these people have woven through all of us and reveal the pictures they create. Although Buck O’Neil is no stranger to baseball fans, thanks to the brilliant work of Ken Burns and Joe Posnanski, it is always helpful to re-read his life, like we do our favorite novels, in hope of discovering something new that deepens our understanding of him as well as ourselves.

“It passed by me, for when I was young I was sure of the good of the world, its beauty, and its ultimate justice. And even when I was broken the way one sometimes can be broken, and even though I had fallen, I found upon arising that I was stronger than before, that the glories, if I may call them that, which I had loved so much and that had been darkened in my fall, were shining even brighter.” These were the words spoken early in their journey, by old Alessandro to young Nicolò in Mark Helprin’s A Soldier of the Great War. After deciding to trek with Nicolò from the outskirts of Rome to the mountains, Alessandro recounted the stories of his youth to his companion: how his world crumbled around him as he fought in and through the Great War and how he slowly rebuilt it, through love and hope and wonder and immense sacrifice.

It is these same things–love, hope, and wonder borne of immense sacrifice–that compelled Buck O’Neil to view baseball as his glory. He dedicated much of his long life to the game and to guiding the young Nicolòs both on the field and in the stands through life, using his words and deeds to illuminate their own glories. He began playing baseball for the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League in 1938, putting up eight excellent seasons before becoming the team’s manager in 1948. In 1955, after managing the likes of Ernie Banks and George Altman, the Cubs hired him as a scout, where he became immensely successful in finding overlooked black talent. Although he attributes much to his years with the Monarchs and as a scout, his most lasting impact on baseball began in 1962, when the Cubs named him a coach.

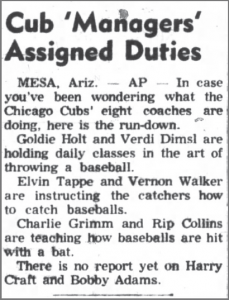

In 1961, Phil Wrigley abolished the traditional method of coaching, instead creating a 13-person staff with a

rotating managerial position that brought the Cubs 4 different managers that season. The move had fans and the media scratching their heads, concluding that Wrigley must be bored and playing an elaborate prank on them all. All Wrigley said to justify the move was that “managers are expendable. I believe there should be relief managers just like relief pitchers” and the Cubs want workers, not bosses.1 Shockingly, however, the lack of a permanent manager was detrimental to the team’s success and looked less funny every day. The “college of coaches” failed, losing 90 games in 1961 and putting up 103 losses in 1962, pushing the team’s cumulative record at Wrigley field to under .500. It was widely ridiculed by fans and sportswriters who declared the Cubs the “most coached and least managed” team in baseball. Even JFK got in a crack, comparing the Cubs to the automation of industries given “it takes ten men to manage the Cubs instead of one!”2

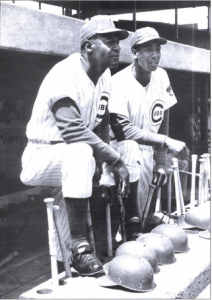

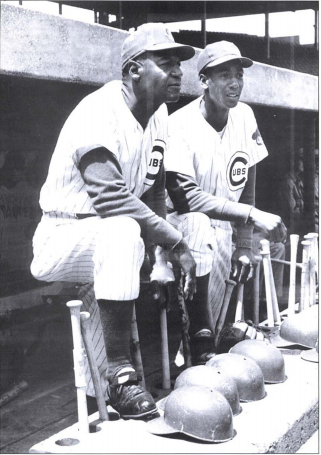

Although the college was largely a failure, the expanded staff enabled the Cubs to hire O’Neil, a move that would otherwise have garnered more backlash. After working as a scout for the club and finding several players including Ernie Banks, the Cubs promoted O’Neil to coach in 1962. It was Ernie Banks who told Wrigley to hire Buck, and he was the first to profit from the hiring, as O’Neil helped him transition from shortstop to first base. Concerning his hiring, GM John Holland declared O’Neil would serve purely as an instructor and would not be under consideration for the revolving managerial position.3 Indeed, the primary motive for hiring him as a full-time coach was so he could remain in the dugout through the entirety of games, and remain in the dugout he did, having been barred from coaching on the field. While his vast knowledge of baseball and his even temperament commanded the respect of his players and peers, O’Neil recognized he would never become manager and so, after two seasons coaching, he returned to scouting.

Regardless of his frustration at being unable to manage, O’Neil held a positive opinion on his time as coach, stating, “coaching is still baseball, and I love baseball. To see a kid and be able to help him–you can’t beat that. That’s my life.”4 He again found the positive side, stating in 1965 that a black man could become a coach and “baseball is much ahead” in race relations compared to much of the country. He was happy in his role as a scout and felt whole so long as he could spend his life serving and fighting for the sport he loved.5

Prior to becoming a soldier in the war, Alessandro visits Munich to see Raphael’s portrait of Bindo Altoviti, which he had wanted to see for some time. In the painting of this young man, Alessandro sees every young man scurrying around Rome. In this one portrait, Raphael captured the persistence of history and a unifying force capable of projecting Bindo into the future and drawing Alessandro to the past. While contemplating this work of art, practice cannons fire in the city, shaking the gallery and deafening many of its patrons, while many others, accustomed to this daily occurrence, carried on with their business. To Alessandro, though, this mundane terror offered him hope: “This was the sound that, on the Western Front, had begun to drown out the music of the world. It was clear for Alessandro, and easily understandable, that for some, music would cease to exist. But not for him, not for him. The electricity rose up his spine and he trembled not from shock, but because, over the sound of the guns, he was able to hear sonatas, symphonies, and songs.”

When Ernie Banks played under O’Neil on the Monarchs, he almost quit baseball. He was st ruggling to make a living, his ankles were both injured, and he was tired of the strenuous travel. One day after arriving at the ballpark, he declared his intention to quit baseball and “go home, settle down, and become a school teacher.” Sure enough, Banks went home. But after a series of proddings from O’Neil, all with the same message—“enjoy the things we’re involved with and everything else will fall into place”—Banks returned to baseball and soon found himself in the Major Leagues.6 Likewise, seven years later, in 1959, O’Neil retrieved Billy Williams after the latter was forced out of baseball due to the racism he encountered. He went to Williams’s house in Alabama, saw the young man laying in his bed, and said, “let’s go out and play some baseball.”7 Gradually, over several days, that’s what the pair did, O’Neil reawakening in Williams his love of baseball until the latter decided to give it another shot.

ruggling to make a living, his ankles were both injured, and he was tired of the strenuous travel. One day after arriving at the ballpark, he declared his intention to quit baseball and “go home, settle down, and become a school teacher.” Sure enough, Banks went home. But after a series of proddings from O’Neil, all with the same message—“enjoy the things we’re involved with and everything else will fall into place”—Banks returned to baseball and soon found himself in the Major Leagues.6 Likewise, seven years later, in 1959, O’Neil retrieved Billy Williams after the latter was forced out of baseball due to the racism he encountered. He went to Williams’s house in Alabama, saw the young man laying in his bed, and said, “let’s go out and play some baseball.”7 Gradually, over several days, that’s what the pair did, O’Neil reawakening in Williams his love of baseball until the latter decided to give it another shot.

Fiercely protective of players like Banks and Williams, as well as all others who played in the Negro Leagues, O’Neil dedicated his later life to bringing them into the limelight. In a country that was becoming ashamed of its actions toward the Negro Leagues, many white people thought it best to forget that segregation ever existed. But O’Neil made that impossible. He never was bitter about the opportunities denied to him because of the color of his skin: “That’s what surprises people about me. I’m not bitter. If I was going to be bitter about anything, it wouldn’t be about baseball but about education. I have no idea what I could have been. Suppose I could have gone to Sarasota High School [which was an all-white school], the University of Florida. All these things I’ll never know, about what kind of man I could have been.”8 But he was also determined to give his fellow black baseball players the appreciation and fame in white America they had routinely been denied.

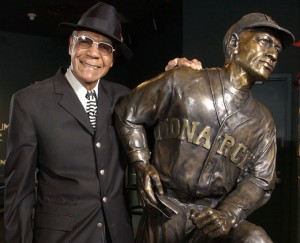

Ken Burns describes O’Neil similarly: “His life reflects the past and contains many of the bitter experiences that our country reserved for men of his color, but there is no bitterness in him; it’s not so much that he put that suffering behind him as that he has brought gold and light out of bitterness and despair, loneliness and suffering. He knows that he can go farther with generosity and kindness than with anger and hate.”9 O’Neil deposited much of this gold and light at 18th and Vine in Kansas City, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM).

The museum opened in 1990, and thanks to an ever-growing list of private donors like O’Neil, it quickly outgre w its room and resides today in a space at least a dozen times larger. It was a place to “honor their guys who built that bridge against that great chasm of prejudice and segregation.”10 O’Neil served as chairman of the NLBM from 1997 to his death in 2006, a position that—with his natural charisma and storytelling ability—enabled him to bring to life again the Negro Leagues, an accomplishment if which O’Neil was the proudest. O’Neil drew together the past and the present. Of the man, Lou Brock said, “Buck is a man God chose for this time. He has seen it all. He saw a transformation of people, of society, of a country. Somebody’s got to be around to tell that story. I think he has been preserved for that purpose.”11 Buck had become the painter and the painting, capturing the past and present in his work with the NLBM and in himself.

w its room and resides today in a space at least a dozen times larger. It was a place to “honor their guys who built that bridge against that great chasm of prejudice and segregation.”10 O’Neil served as chairman of the NLBM from 1997 to his death in 2006, a position that—with his natural charisma and storytelling ability—enabled him to bring to life again the Negro Leagues, an accomplishment if which O’Neil was the proudest. O’Neil drew together the past and the present. Of the man, Lou Brock said, “Buck is a man God chose for this time. He has seen it all. He saw a transformation of people, of society, of a country. Somebody’s got to be around to tell that story. I think he has been preserved for that purpose.”11 Buck had become the painter and the painting, capturing the past and present in his work with the NLBM and in himself.

In 2006 the baseball Hall of Fame’s Special Committee on the Negro Leagues held a special vote to consider those who had been previously overlooked by the HOF. Among consideration was Buck O’Neil, who seemed like a sure candidate due to the publicity surrounding him since Ken Burns’s documentary series. However, perhaps because the committee did not know what to make of his unique 80 years in baseball—perhaps his playing stats weren’t good enough or he didn’t do enough as a manager—he missed the cutoff by nine votes. But rather than dwell on his disappointment, he turned his “failure” into yet another victory for the Negro Leagues (when asked why he would do this, O’Neil replied “Son, what has my life been about?”).12 In his final public appearance before his death three months later, O’Neil spoke at the induction ceremony for the 17 people who had acquired enough votes, and it was a speech that highlighted the very best of Buck O’Neil:

Next, Negro League baseball. All you needed was a bus, and we rode in some of the best buses money could buy, yeah, a couple of sets of uniforms. You could have 20 of the best athletes that ever lived. And that’s who we are representing here today. It was outstanding.

And playing in the Negro leagues — what a lot of you don’t know. See, when I played in the Negro leagues — I first came to the Negro leagues — five percent of Major League ball players were college men because the major leaguers wanted them right out of high school, put them in the minor league, bring them on in. But Negro leagues, 40 percent of Negro leagues, leaguers, were college men. The reason that was, we always spring trained in a black college town, and that’s who we played in spring training, the black colleges. So when school was out, they came and played baseball. When baseball season was over, they’d go back to teaching, to coaching, or to classes. That was Negro League baseball. And I’m proud to have been a Negro league ball player. Yeah, yeah.

And I tell you what, they always said to me Buck, “I know you hate people for what they did to you or what they did to your folks.” I said, “No, man, I — I never learned to hate.” I hate cancer. Cancer killed my mother. My wife died 10 years ago of cancer. (I’m single, ladies.) A good friend of mine — I hate AIDS. A good friend of mine died of AIDS three months ago. I hate AIDS. But I can’t hate a human being because my God never made anything ugly. Now, you can be ugly if you wanna, boy, but God didn’t make you that way. Uh, uh.

So, I want you to light this valley up this afternoon. Martin [Luther King] said “Agape” is understanding, creative — a redemptive good will toward all men. Agape is an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return. And when you reach love on this level, you love all men, not because you like ‘em, not because their ways appeal to you, but you love them because God loved them. And I love Jehovah my God with all my heart, with all my soul, and I love every one of you — as I love myself.

Fittingly, for a person who saw the beauty in everything, who never let it be drowned out by hatred or fear, he ended his talk with a song, the greatest thing in life is loving you.

At the end of the journey, after Alessandro tells Nicolò they must part ways so he can walk the final steps of his path alone, Nicolò asks him what can be done about all of those people Alessandro mentioned who died in the war: “I want to do something for all the people in the time of which you spoke. I want to very much, but I can’t, can I.” “But you can,” Alessandro replies, “It’s simple. You can do something just, and that is to remember them. To think of them in their flesh, not as abstractions…to draw no lessons of history on their behalf. Their history is over. Remember them, just remember them—in their millions—for they were not history, they were only men, women, and children. Recall them, if you can, with affection, and recall them, if you can, with love.”

Buck O’Neil made it possible for us to do so for every Negro Leagues player, no matter how much or little success he accrued. But the more challenging thing is how we must remember Buck himself. Nicolò, after going on this physical, historical, and spiritual journey with Alessandro, continues on his way, and we do not see what becomes of him, or how, precisely, he recounts Alessandro to his family and friends, or whether he follows the old man’s advice.

It is fortunate that we, then, are the authors of Nicolò, and we can each write his ending. Perhaps we will view O’Neil in the way that Reggie Jackson does, with the man transcending his human form: “I believe that people like Buck and Rachel Robinson and Martin Luther King and Mother Theresa are angels that walk on earth to give us all a greater understanding of what it means to be human.”13 Or maybe Buck will remain wholly human, and we are to find the shining glories in the mundane intricacies of his daily life. Or maybe he and Alessandro are right, that it doesn’t really matter how one is remembered as long as they are remembered, because differences in memory invite conversation, and conversation is humanity.

1 George F, Will, “A Nice Little Place on the North Side: Wrigley Field at One Hundred,” 106.

2 Richard J Puerzer, “The Chicago Cubs College of Coaches: An Innovation that Failed,” 6.

3 The Belvidere daily republican, Nov. 10, 1962.

4 Kevin Newell, “The Buck stops here: an outstanding player, manager, coach, scout, and ambassador for baseball; why isn’t Buck O’Neil in the hall of fame?” Coach and Athletic Director, November 2004.

5 The La Crosse Tribune, Mar 21, 1965.

6 Piqua Daily Call, October 29, 1975.

7 http://www.kansascity.com/sports/mlb/kansas-city-royals/article110949822.html

8 John B. Holway, “Black Diamonds : Life in the Negro Leagues from the Men Who Lived It.”

9 Buck O’Neil, “I Was Right On Time”, xii.

10 Galveston Daily News, Oct 30, 1995.

11 http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/07/sports/baseball/07oneil.html

12 http://sportsworld.nbcsports.com/buck-oneil-joe-posnanski/

13 Indiana Gazette, October 7th, 2006.

It was Charlie Grimm, then a VP of the Cubs, who decreed that Buck remain in the dugout and never on the coaching lines. Buck stated that in his autobiography.

Thank you so much for such an uplifting article.