The year was 1938, 25 years before the popularization of “nerd”, the place was Wrigley Field, three stories and six hours away from his mom’s basement, and the man was Coleman Griffith, father of sports psychology. Long before there was BAM or WAR1 or DRA, there was Coleman Griffith, a camera, 154 daily reports, and fans equally intrigued and confused by statistics. After the 1937 Chicago Cubs blew a seven game lead to finish two games behind the New York Giants, Phil Wrigley brought in Griffith to assist in overcoming what he believed to be primarily a lack of mental fortitude, particularly on behalf of the manager, Charlie Grimm.

Griffith at University of Illinois

Griffith ran the country’s first athletics research laboratory from 1925 to 1931 during which he focused on basketball and football. He believed, “the more mind is made use of in athletic competition, the greater will be the skill of our athletes, the finer will be the contest, the higher will be the ideals of sportsmanship displayed, the longer will our games persist in our national life, and the more truly will they lead to those rich personal and social products which we ought to expect of them.”2 Unable to win over the university’s football coach, who had not seen any improvement in the team and was unlikely to encounter Tom Brady, Griffith had his department shut down in 1932 and found himself relegated to an administrative position with the institution.

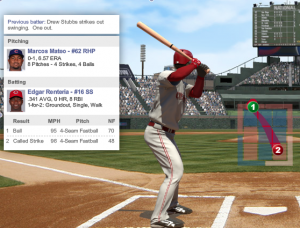

In addition to Griffith, Wrigley hired John Sterrett, a graduate of Griffith’s department, to follow the team on the road and record data and film the practices. Together, the two sought to collect “a statistical record of each ball pitched to a Cub player during the season, analyzed according to (a) types of balls pitched, (b) habitual sequences in types (c) successful hitting by types, (d) persistent missing by types, (e) situation for each pitch, score, men on base, etc., (f) seasonal variations,” and do the same for each opposing batter.3 Sterrett attended all spring training and seasonal games, recorded this information for each pitch, and submitted daily reports to Griffith. After the first two months, Griffith determined the key to improving the Cubs lay in the difference between physiological and practical limitations of a player; if they were to alter their practice regimens to be more efficient, players could achieve results widely believed to be physically impossible.4

By the end of May, Griffith asked Sterrett to help implement new practice regimes based on his data. He wanted to create more routine practices that featured game-like factors, including full-speed at-bats used to instruct players how best to handle each ball-strike count. He further required Sterrett and the coaching staff to conduct “achievement tests” to assess players’ speed, strength, accuracy, coordination, and “visual judgement.”5 The results would feed back into practice regimens as well as scouting tools.

Although Chicago was fairly accustomed to Wrigley’s attempts to modernize and technologize the Cubs, this move was met with much confusion and some ridicule. Players were not used to working with such highly educated professionals, and they had difficulty adjusting to the newly implemented practice routines. As one baseball writer put it, “he’s got the boys in a state of such confusion they don’t know whether they’re in New York today or at Santa Catalina Island [the location of their spring training facility].”6 The most resistance, though, came from manager Charlie Grimm, whose temper and precarious job situation led him to openly reject Griffith’s work. Sterrett wrote Griffith on April 26th to voice his concern about Grimm: “I am convinced that Grimm is knocking our work as much as he can. Everything we say or do is reported to him and these are, in turn, passed on to the players. Grimm said to one of the players that he was afraid we might say or do something worthwhile and that if the players or the head office knew about it, it would put him in a bad light.”7 Grimm repeatedly told his players to ignore Griffith’s suggestions.

In mid-July, with the Cubs in fourth place, Wrigley fired Grimm, replacing him with catcher Gabby Hartnett, a move Wrigley said he had been contemplating for some time. This change seemed to spark the team, prompting them to win 11 of 17 to close out the month. Sterrett also found the players to be immediately more open to and invested in his work: “I thought I enjoyed the confidence of the players one hundred percent, but it was only one-tenth of what I am getting now. . .. None of the players wanted to be seen talking to me, if Grimm were around.”8 The managerial change continued to generate success, as the Cubs made it to the World Series that season, but by that point, the good will between Hartnett and Griffith had dissipated. Griffith found the former to be “stubbornly traditional” and “vindictive with players who crossed him.”9 In his year-end report, Griffith wrote that Hartnett ““was not at all a smart man. . .. Not a teacher nor would he have the ability to adapt himself to any other style of training and coaching but that with which he had been familiar throughout his playing career.”10

Wrigley looked to the team’s results, though, and decided to try and keep both Hartnett and Griffith. However, unwilling to move his family to Chicago, Griffith assumed a part-time role with the team. His work was supplemented by statistician Chester Lynn Snyder, who took on much of Sterrett’s former role, attending games and compiling statistics to be analyzed in the offseason. He attended every game, recording every at-bat in a notebook, complete with “the batter’s name, the pitcher’s name, the baseball diamond, and a rectangle to represent the strike zone. For each pitch, Snyder recorded pitch location and where the ball was hit on the field.”11

The data was compiled in the offseason, and a total of nine batters received personalized reports of their seasons with notes on how to improve. Phil Cavarretta, for instance, received a detailed breakdown of each at-bat and series of at-bats against different pitchers, such as New York Giant Harry Gumbert: “In the strike area low and inside Cavarretta hit two curves and a fast pitch for outs, hit a fast pitch for a safe hit, and let four fast pitches go for called strikes. In the ball area of this section, he hit a fast pitch for a hit. He was hit by a curve ball and took seven other pitches for called balls.”12

Griffith also compiled pitching information, but that was primarily to assist in tactical managerial decisions. For example, in 1941, manager Jimmie Wilson wanted to know how to handle late-inning pitching and was shown data from 1939-1941 that concluded, “the best thing to do when a pitcher let a runner on base in the ninth inning was to take that pitcher out and put in a reliever.”13

During this time, however, the Cubs accrued little success, and the program’s viability was questioned. Griffith left after the 1939 season, and Snyder left in 1942. Bill Veeck recalls working on the initial project thusly:

“My first job was to get the local high school coaches to send us their best three or four kids and to supervise the building of the clubhouse in which we were going to install both our kids and our testing equipment.

Just before the season ended, the psychologists picked their starting lineup, based upon their tests, and the scouts picked their team based upon their eyesight.

The anticlimax to this excursion into the Brave New World was that the scouts’ team clobbered the psychologists’ team. About 10 of the players picked by the scouts eventually progressed up to the high minors. Of the players picked by the psychologists, the scoreboard read zero.”14

Though the results were questioned and seemed to do little to help the team, Wrigley kept hiring various statisticians to record similar data, though without the detailed reports. Despite the lack of team success, which was probably due to Wrigley’s stinginess and disapproval of trading for star players, several individual players attributed their success to Griffith. Bill Lee, who led the NL in ERA and wins in 1938, used Griffith and Sterrett’s film of his pitching motion to improve over the season.15

By the late 1940s, other teams began hiring statisticians to do similar work. Though these teams often found more success than did the Cubs, Wrigley kept his team ahead of the statistical curve, bringing in a computer in the 1960s to process larger quantities of data more efficiently. Around this time, GM John Holland used some sort of data to determine “clutchness,” on which he based the yearly contracts of each Cubs player.16 Whether it was the use of statistics or the fact that the team finally lucked into good players, like Ernie Banks, the Cubs achieved some success under Holland, winning several pennants. Although they failed to achieve the ultimate prize, baseball fans as a whole received one from them in 1938.

Lead photo courtesy Jasen Vinlove—USA Today Sports

1 Speaking of war (what is it good for?), many psychologists believed in 1938 that baseball was keeping Americans out of the war: “A man who gives vent of his emotions at a ball game isn’t likely to go home and beat up his wife or commit any other crime because his mental “explosion” at the ball park has acted as an emotional safety valve,” they theorized. “In central Europe, they have no sports compared to base ball, no harmless emotional safety valves…as a result many of them take out their aggressions in politics.” (The Chicago Times, October 4, 1938.)

2 Christopher D. Green, “Psychology Strikes Out: Coleman R. Griffith and the Chicago Cubs,” History of Psychology 6 no 3, 268.

3 Alan S Kornspan, “A Historical Analysis of the Chicago Cubs’ Use of Statistics to Analyze Baseball Performance,” NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture, Volume 23 no 1, 20.

4 Coleman Griffith, General Report, 1939, 88-90.

5 Green, 272.

6 The Morning Herald, May 18, 1938.

7 Griffith, 48.

8 Ibid, 58.

9 Green, 277.

10 Ibid, 278.

11 Kornspan, 23.

12 Green, 279.

13 Kornspan, 25.

14 The News-Journal, November 7, 1965.

15 Green, 279.

16 Ibid, 282.

Amazingly interesting. Thank you.