Through Ladies’ Days and Girls’ Nights, baseball has long tried to appeal to women, achieving varying degrees of success. For many of these promotions, it is men who have pieced them together, often resulting in backlash as current female fans feel patronized or ignored. Though baseball has had a tough job marketing to women, it has achieved monumental success in allowing women to market the game. Two women in particular, Cubs’ executive Margaret Donahue and Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley, re-invented team promotion so thoroughly their innovations are used by every MLB team today.

In 1919, Bill Veeck hired Margaret Donahue as a stenographer and bookkeeper, and promoted her to corporate secretary in 1926. She was the first woman to fill that role, something Veeck was very proud of, announcing it at the league meetings thusly: “I have, or rather our board of directors has, elected a new club secretary, a woman, the only woman secretary in organized ball. Her name is Miss Margaret Donahue. … We feel that in Miss Donahue we have added a real asset to our club organization.”1 Donahue worked in this position for 32 years, handling much of the day-to-day business of the club, such as recording ticket sales, answering letters, and assigning press passes. Upon her retirement in 1958, Phil Wrigley declared her “a nationally acknowledged authority on the intricacies of baseball rules and regulations” who had been a tremendous asset to the club.2

Her real influence came in the land of marketing, though. She was determined to make Wrigley suitable for families, and having gained the trust of Veeck and others, she set to work actualizing this plan in 1929. She initiated the selling of season tickets and tickets at off-site locations in January, and by February, the team had smashed its pre-season sales record. This success encouraged management to implement another of Donahue’s ideas, reduced prices for kids 12 and under.3 The inspiration for season tickets came from Donahue’s observation that people “would often save seats for people on game day, and sometimes they didn’t come. And they were saving some of their best seats, and people weren’t coming. So she thought they would probably be forced to come if they bought the tickets in advance.”4 This hypothesis proved correct, as the 1929 Cubs drew 1.4 million fans, though I’m sure the on-field success wasn’t much of a deterrent, either.

She was so involved with the team and dedicated to its fans that by 1933, Veeck hypothesized that nobody was “as known to as many regular fans—via telephone and correspondence—as Miss Donahue.”5 She made sure to personally look after children who were temporarily lost, offering them candy, gum, and baseball stickers while she tracked down their parents, perhaps one of the few roles in  baseball completely unsuitable for a man.6 The theory was that if the baseball experience at Wrigley was personal and friendly, fans would be more inclined to pay for games, just like the possibility of encountering a mustachioed Theo makes me more inclined to pay for games.

baseball completely unsuitable for a man.6 The theory was that if the baseball experience at Wrigley was personal and friendly, fans would be more inclined to pay for games, just like the possibility of encountering a mustachioed Theo makes me more inclined to pay for games.

Based on her knack for advertising, Veeck left her in charge of Ladies’ Day, for which she expanded advertisement to ensure both individual women and ones with families could routinely enjoy baseball. Her success was so fundamental to the team that some thought she should take over the Cubs after Veeck’s death in 1933. While that did not happen, she did become Vice President in the 1940s, a title she kept until her retirement.

Indeed, as perhaps only a woman can, she took over several scouting and player development tasks while maintaining her work as a secretary. Her influence spread to Bill Veeck Jr., who went on to own the Chicago White Sox, St. Louis Browns, Cleveland Indians, and the Milwaukee Brewers. Like Wrigley, he considered her somewhat of a savant, stating, “Donahue is as astute a baseball operator as ever came down the pike. She has forgotten more baseball in her 40 years with the Cubs than most of the so-called magnates will ever know.” When Donahue blamed the Cubs’ failures on the team’s lack of a farm system, Veeck listened and took that lesson with him to the Indians, where he implemented a farm system and searched for talent high and wide, including the Negro Leagues.7

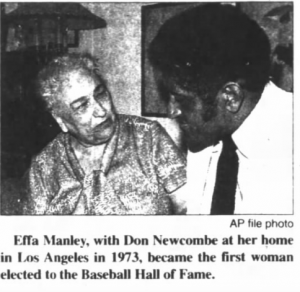

Effa Manley became co-owner of the Negro Leagues’ Newark Eagles in 1935 after marrying Abe Manley, making her the *second female  owner (the first being Olivia Taylor). In 2006, she became the first female elected to the Hall of Fame. Like Donahue, she began by overseeing the day-to-day operations of the team, arranging travel schedules and managing payroll. She helped develop the Eagles into a championship team and did much to advance and protect the rights of all players in the Negro Leagues to prevent them from “being sucked into the cotton mills, steel mills, and coal mines.”8 Also like Donahue, she quickly grew out of this role, moving toward the promotional aspects of the team, which she often incorporated with the Civil Rights Movement and the Newark community in general.

owner (the first being Olivia Taylor). In 2006, she became the first female elected to the Hall of Fame. Like Donahue, she began by overseeing the day-to-day operations of the team, arranging travel schedules and managing payroll. She helped develop the Eagles into a championship team and did much to advance and protect the rights of all players in the Negro Leagues to prevent them from “being sucked into the cotton mills, steel mills, and coal mines.”8 Also like Donahue, she quickly grew out of this role, moving toward the promotional aspects of the team, which she often incorporated with the Civil Rights Movement and the Newark community in general.

In 1947, she orchestrated the sale of Larry Doby to Veeck Jr. and the Indians, forcing him to pay fair compensation rather than stealing the talent and bankrupting the league, as had been the norm. Veeck Jr. paid $15,000 for Doby, whereas Branch Rickey had offered Jackie Robinson a minor league contract and paid nothing to the Monarchs. Before this transaction, Manley had attempted to sue Rickey, but was lambasted by the black media, who believed she was inhibiting Negro League stars from playing in the MLB.9

Manley had always been aware of the black person’s position in society, though, and used her position as owner almost immediately to influence change. In 1939 she held the first of several Anti-Lynching Days at the ballpark, prompting black fans to gather and rally for change. She fashioned sashes for her ushers that read “Stop Lynching,” and they moved throughout the crowd collecting money for a number of anti-lynching efforts.10 Further promotions included a number of charity games, and through her prominence in the Leagues, she recruited or shamed many other teams into participating and hosting their own. These games raised funds for the NAACP, the Red Cross, and community hospitals, among others.11

In the offseason and during any downtime, she secured positions in the community for her players, so they could contribute and become active leaders. Like Margaret Donahue, she believed baseball was about family and community, so beginning in 1940, the team offered free admission to children.12 Through these programs, the Eagles became synonymous with Newark, forming the tightest bond between community and team that professional baseball had seen to date.

Manley also did much to revolutionize the owner’s relationship with the press. It was at times quite contentious, but she also understood it was a powerful tool for both advancing the Negro Leagues and civil rights. In 1942, after the Eagles had been banned from paying at Oriole Park, Manley wrote a letter to Buster Miller, one of the most influential writers at the largest black paper, the New York Age, urging him to rally people to this cause.13 After the Eagles were sold in 1948, influential black writer Wendell Smith wrote about this relationship. Opening with the sarcastic remark, “the indignities she has suffered have been caused, no doubt, by coldhearted newspapermen who refuse to let her operate both the Newark Eagles and their respective newspapers,” Smith goes on to paint Manley as a delightful woman who took as much as she gave.14 Manley was “gracious, charming, eccentric,” and utterly devoted to protecting the Negro Leagues, using the press as one of her many instruments. Though frustrating at times, the press and Manley understood the necessity of their relationship likely better than any other exec at the time.

Together, Donahue and Manley built the foundation for all** modern days at the park. Their understanding and support of the wide appeal of baseball is captured in the diverse crowds attending games at all levels and in the efforts of teams today to embrace their communities. Margaret Donahue and Effa Manley are names with which every baseball fan should be familiar, because they made themselves familiar with every baseball fan.

*An earlier edition of this article claimed Manley was the first female owner, but Taylor owned the Indianapolis ABCs over a decade earlier.

**Except at parks where it costs about 4 kidneys to take one’s family. Lookin’ at you, Fenway.

Lead photo courtesy Jerry Lai—USA Today Sports

1 Paul Dickson, “Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick,” 20.

2 http://www.thenationalpastimemuseum.com/article/margaret-donahue-first-lady-front-office

3 Dickson, 21.

4 Chicago Tribune, July 22, 2013.

5 Freeport Journal-Standard, March 13, 1933.

6 George Castle, “Cubs’ Donahue far ahead of her time as baseball’s first female executive,” Chicago Baseball Museum.

7 John Owens, “Female Cubs executive left her mark on the big leagues. “ Chicago Tribune. June 22, 2104.

8 The Pentagraph, December 5, 1976.

9 http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/mlb_negro_leagues_story.jsp?story=effa_manley

10 Lisa Doris Alexander, “Effa Manley and the Politics of Passing,” 72.

11 Jeff McArthur, The American Game, 71.

12 Tara Moriarty, “More Than a Game: The Legacy of Black Baseball”, 73.

13 New York Age, June 6, 1942.

14 The Pittsburgh Courier, September 18, 1948.