Much has been made about the Cubs’ youth, and rightfully so. The team boasts an excellent crop of youngsters who are more concerned about the greatness of the future than the heartbreak of the past. They are helping to introduce a new brand of Cubs baseball that is unfamiliar to any fan under the age of 110. But they are not the first youth movement to reinvent the Cubs, and they are perhaps not even the most important. That title belongs to the teams of the early 1900s, without whom the “Cubs” would not exist.

The Cubs were first known as the White Stockings, a name that hung around until 1889, after which the team became the Colts, due to the young ages of many prominent players. In 1898, team manager Cap Anson left the club after his contract was not renewed, prompting newspapers to dub them the Orphans. This name stuck around for about a decade. Then, in 1901, when Chicago gained an American League team and the few remaining veterans jumped to Comiskey’s White Stockings, the Orphans became the Remnants.1 When the team wore Panama hats during games in 1903, they were nicknamed the Panamas, but after suffering a lengthy losing streak (that the Washington Evening Standard appropriately summarized as “base ball voodooism”), the team nixed the hats in favor of regular baseball caps.2 From there, every sportswriter in the country took a crack at naming the team, but as herd mentality has it, the nicknames all played on the team’s youth: the Microbes (1903), the Zephyrs (1905), and the Spuds (1906).

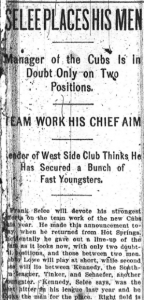

After the mass exodus in 1900 and 1901, the team brought in new manager Frank Selee to corral a team of youngsters. The team included 11 players under the age of 25, headlined by pitcher Carl Lundgren, outfielder Davy Jones, and infielders Joe Tinker and Johnny Evers. The lineup was further revamped when Selee forced Frank Chance to move to first base in order to make room for new catcher Johnny Kling. This youth movement continued over the next several seasons, and the team climbed up the National League standings, finishing first from 1906-1908.

On March 27th, 1902, the Chicago Daily News, likely via a typesetting error, referred to this young team as the Cubs. Other Chicago newspapers quickly picked up on this nickname, though many of them placed the name in quotations, signifying its unofficial nature. By the beginning of June, though, the quotations were largely dropped, and–though still unofficial–the team became known as the Chicago Cubs. The name gained national traction throughout the season, as well. By September, newspapers in Washington, New York, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis referred to the Chicago team exclusively as the Cubs. However, many newspapers continued to use ‘Orphans’ and ‘Colts,’ and ‘Cubs’ faced new competitors over the next five seasons.

On March 27th, 1902, the Chicago Daily News, likely via a typesetting error, referred to this young team as the Cubs. Other Chicago newspapers quickly picked up on this nickname, though many of them placed the name in quotations, signifying its unofficial nature. By the beginning of June, though, the quotations were largely dropped, and–though still unofficial–the team became known as the Chicago Cubs. The name gained national traction throughout the season, as well. By September, newspapers in Washington, New York, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis referred to the Chicago team exclusively as the Cubs. However, many newspapers continued to use ‘Orphans’ and ‘Colts,’ and ‘Cubs’ faced new competitors over the next five seasons.

The 1907 team was the first to have a “C” on the uniform and also the first to be called the Cubs on the home scoreboard.3 Toward the beginning of the season, the team’s manager and first baseman, Frank Chance, insisted on the newspapers calling the team the Cubs.4 Famous baseball writer Bozeman Bulger helped entrench the name when he wrote a column explaining its origin, stating the team is “‘Cubs’ to the world of sport.”5 This article was reprinted in newspapers from almost every state, and, like the Cubs’ on-field opponents, the final holdouts began to fall.

Though ‘Cubs’ gained almost universal acceptance by July of 1907, the species of Cub remained up for debate. Even individual newspapers could not come to a decision; on April 15th, the Daily Tribune wrote, “Chicago’s cubs showed their polar bear ancestry yesterday and also demonstrated their cross-breed with the cinnamon variety by trimming the St. Louis Cardinals in a hot, spicy game.” On July 4th, perhaps overtaken by jealousy of the White Sox having a mascot, the Cubs hired brown bear cubs as mascots for their doubleheader against Cincinnati. Although they realized that—despite many accounts of the contrary—young boys are more suited to stand in front of large crowds than are live bears, and therefore did not parade the cubs around the field, the animals still became the popular depiction of the Cubs.6

The ambiguity, however, was heightened by the 1907 World Series, in which the Cubs beat the Tigers, 4-0-1. For the series, the team donned crisp white uniforms emblazoned with a large, white bear. The team itself chose the polar bear as the mascot, but despite ceding to the team on the name ‘Cubs,’ newspapers remained loyal to the brown bear.

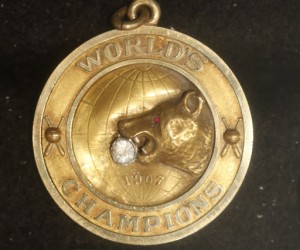

Tired of this pointless battle, the Cubs craftily chose a third option that it introduced to the world at the unveiling of the team’s World Series medals. These medals featured “the profile of a bear cub holding a large diamond in his teeth, which are to be of aluminum. A ruby represents the cub’s eye.”7 The bear itself appears to be neither polar nor brown, and perhaps not a bear at all, or at least not one known to the world in 1907. The team doubled down on this strategy the following season, when they introduced a mascot so terrifying it forever altered the argument. Now, the question concerned not the nature of the mascot but the best methods for erasing it from history. So effective was this move that it closed the argument for over a century, until the current young Cubs gained a young cub of their own in Clark.

Tired of this pointless battle, the Cubs craftily chose a third option that it introduced to the world at the unveiling of the team’s World Series medals. These medals featured “the profile of a bear cub holding a large diamond in his teeth, which are to be of aluminum. A ruby represents the cub’s eye.”7 The bear itself appears to be neither polar nor brown, and perhaps not a bear at all, or at least not one known to the world in 1907. The team doubled down on this strategy the following season, when they introduced a mascot so terrifying it forever altered the argument. Now, the question concerned not the nature of the mascot but the best methods for erasing it from history. So effective was this move that it closed the argument for over a century, until the current young Cubs gained a young cub of their own in Clark.

We often like to talk about the past as something from which we have escaped, and with the brightness of the future, Cubs fans in particular have little encouragement to revisit history. But it is also important to know from where we’ve come and how easily things could have been vastly different. While it is true that we have all escaped the clutches of that mascot, without the rudimentary technology of the early 1900s, we would all be rooting for the Chicago Orphans. And I think we can all agree that Kris Bryant’s beauty would decline by at least 15 percent if he were to hit home runs while wearing a saddened, homeless child stitched onto his arm.

1 Pittsburgh Press, October 6, 1901.

2 Washington Evening Standard, June 23, 1903.

3 Art Ahrens, “Chicago Cubs: Tinker to Evers to Chance,” 56.

4 Lauren Pernot, “FROM COLTS TO CUBS,” in Before the Ivy: The Cubs’ Golden Age in Pre-Wrigley Chicago, p. 98.

5 Jackson Daily News, June 4, 1907.

6 Chicago Daily Tribune, July 5, 1907.

7 Chicago Daily Tribune, November 24, 1907.