It is no secret that baseball, since its creation, has been uniquely tied to the fundamental nature of America. Its cultural and political nature is woven into the game at every level, and each game is a microcosm of American history. There are thus many examples from which to choose, but the efforts to install lights in Wrigley Field in particular touches on several elements of American and human nature that are infrequently examined together. The story focuses on a headstrong, money-seeking man who believes beyond rational justification it is his moral duty to protect the purity of baseball, and in doing so, exhausts each political avenue open to American citizens.

Phil Wrigley was a shrewd businessman who believed in innovation and ingenuity, and did much to positively impact the experience of baseball. But, as a businessman, he constantly did a risk-reward analysis for each of his projects, and for 42 years, he thought the risk of night baseball vastly outweighed its monetary reward. He was the first to install lights in other areas of the ballpark—in the late 1930s, Wrigley installed lights in the concourse to light concessions stands and in the scoreboard to denote the winner of each game—but refused for years to light the field.

Six years after the first night baseball game was played (in Cincinnati against the Phillies on May 24, 1935), Wrigley sent Bill Veeck to investigate a hydraulic lighting system that enabled light poles to be raised and lowered in a telescopic manner. Unfortunately, the system would cost $70,000, far more than Wrigley was willing to pay, as he did not believe night games would generate enough compensatory revenue. The team tried again in the offseason, going so far as to order the necessary construction material and strike a deal with the city to have no game end later than 8 pm, so as to not disturb the residents. But then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and Wrigley called off the project in favor of proving his patriotism by donating the steel to the war effort’s defense plant. However, it ironically likely ended up as lighting for the local race track, which had begun holding nighttime events.1

Throughout the following four years, after FDR called for an increase in night games to foster morale and provide entertainment for those who spent their days dedicated to the war effort, Wrigley submitted various plans to install light s. The first plan included second-hand and wooden parts, but it, along with its successors, were rejected by the War Production Board. Urged by FDR, the Cubs entered into a verbal agreement to play “home” night games at Comiskey while lights were installed at Wrigley.2 But after losing rights to 160 tonnes of steel, Wrigley ceased these talks (much to the relief of the White Sox), unwilling to freely give up day games at Wrigley. He did manage to assemble a temporary lighting system to host tryouts and exhibitions for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League in 1943, but they were quickly removed later that year.3

s. The first plan included second-hand and wooden parts, but it, along with its successors, were rejected by the War Production Board. Urged by FDR, the Cubs entered into a verbal agreement to play “home” night games at Comiskey while lights were installed at Wrigley.2 But after losing rights to 160 tonnes of steel, Wrigley ceased these talks (much to the relief of the White Sox), unwilling to freely give up day games at Wrigley. He did manage to assemble a temporary lighting system to host tryouts and exhibitions for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League in 1943, but they were quickly removed later that year.3

By the 1960s, other owners began pressuring Wrigley to install lights, arguing they lost revenue whenever their teams played in Wrigley Field. In 1962, Wrigley, after staunchly avoiding the topic for the past decade, again acquiesced to the demand for lights, but the lights would only be used for Bears games, as he still did not believe attendance during night games would be sufficient enough to cover the installation, electricity, and maintenance costs. The stubborn owner even suggested the Lake View Citizens Council create a petition against night baseball on the charge it would disturb their residences. Wrigley further opposed the pressure from his fellow owners on the basis that baseball’s primary target is young children, who would be unable to attend night games, and, logically, baseball fandom would cease to be. Further, Wrigley had been at least publicly a longtime believer that baseball was meant to be played in the daytime.4

In response, lawyer and stock owner of the Cubs, William Shlensky, filed a suit against the team, arguing the team’s refusal to play night games had lowered the value of his stocks and seeking a court order forcing Wrigley to finally install lights. He contended this refusal to play night games inhibited the team from procuring top free agents, which fed back into low attendance numbers and low revenue. He sought compensation for a five-year decline in stocks. Addressing this suit, Wrigley stated that it was not serious, as in America, anyone could be sued for any small issue, and were the Cubs to play night games, attendance would be lowered due to competition from movie theatres and shopping centers.5 The case was dismissed in circuit court.

After Phil Wrigley’s death in 1977, his son, William Wrigley, took control of the team and reversed his father’s position on night baseball. Demand for lights began again in 1981 when the Tribune Company called for night games. In opposition, the Citizens United for Baseball in the Sunshine was formed and petitioned the state legislature to ban night baseball at the ballpark, citing the same arguments made by Phil Wrigley throughout the years. The Cubs threatened to move stadiums if this legislation was passed, but nonetheless, on August 24, 1982, Illinois governor James Thompson signed the statute prohibiting night baseball. A year later, the Chicago City Council passed an ordinance by a vote of 42-2 banning all outdoor lights at Wrigley Field. The avenues his father had taken proved robust roadblocks for Phil Wrigley.6

The team took the state and city to court, but had the misfortune of filing with a judge who happened to be a rather old-school baseball fan. Judge Richard Curry, in his opinion, wrote “that the awe-inspiring sight of a home-run ball bouncing high off the pavement of Sheffield or Waveland Avenues is just too Chicago not to be protected in perpetuity.”7 In essence, nighttime baseball would degrade the product and run counter to the essence of the city.

But luckily, the joys of capitalism saved the Cubs from becoming an arcane blight on the game. Wrigley increased threats to move the team elsewhere in the city, and MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn threatened to prohibit the Cubs from playing postseason games in Wrigley on the basis that a slate of day games would negatively impact TV revenue.8 Three years later, as a result of this economic pressure, the Illinois legislature passed new legislation allowing night games, and the following year, the Cubs struck a deal with the city council, agreeing to a number of conditions in exchange for the ability to play night baseball. The Cubs could play no more than 18 night games per season through 2002, could  not sell beer past 9:20pm, and could not play organ music after 9:30, but they could finally play under lights.9

not sell beer past 9:20pm, and could not play organ music after 9:30, but they could finally play under lights.9

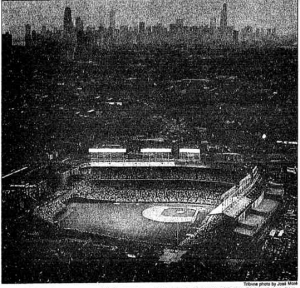

The first game under lights, on August 8th, 1988, was cut short after three and a half innings due to a torrential downpour. But like the first drops of water after a long drought, this rain signified relief, relief for all those who campaigned for 53 years, relief for everyone who wanted to see playoff games at Wrigley, and relief for Phil Wrigley, whose legacy would no longer be tarnished by his outdated and misguided fight for the purity of the game. As the lights reflected off the pools of water gathering around the field and in the stands, they illuminated the result of a 53-year slog through American consumerism by a man who captured the essence of America.

Lead photo courtesy Jerry Lai—USA Today Sports

1 Stuart Shea, “Wrigley Field: The Long Life and Contentious Confines of the Friendly Confines, 225.

2 Chicago Tribune, January 21, 1942.

3 Shea, 230.

4Ibid., 280.

5 Daily Standard, March 18, 1966.

6 http://www.nytimes.com/1985/05/28/us/let-there-be-light-the-cubs-plead.html

7Ibid.

8 Gettysburg Times, August 29, 1984.

9 Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1988.