By one measure, Kyle Schwarber’s performance in May was historic. It wasn’t his 51 wRC+, or his .120 batting average, which were bad, but hardly remarkable given that worse marks in both categories have already been posted this season (if you think Schwarber was an ineffective leadoff hitter, Royals leadoff man Alcides Escobar has a wRC+ of 13 for the season).

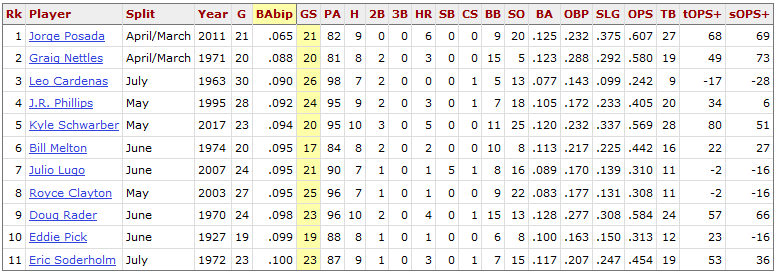

No, it was Schwarber’s .094 BABIP, which ranks as the fifth-worst monthly BABIP of all time (min 80 PA). The list of players who have managed to have a BABIP of .100 or below over the course of a month is fairly short:

Glossing over the fact that Jorge Posada somehow leads this list by 23 points, this must be great news for Schwarber, in a way. The 24-year-old had one of the unluckiest months in baseball history, and with a bit of batted ball luck he’ll be able to spark the inevitable offensive resurgence of the entire team.

The Statcast batted ball data further supports the notion that Schwarber’s bad luck is the main culprit in his poor line. His xwOBA, based on the exit velocity and launch angle of all of his batted balls, is .337, over 50 points higher than his actual mark. That’s not quite at the level of his .364 wOBA in his debut season, but it would still represent a significantly more valuable offensive contribution. So we can all relax and assume that simple regression will take its course, right?

Not so fast. There are reasons why hitters might run a below-average BABIP. Not a .094 BABIP, of course, but .300 is not the level every hitter will regress to. Fly ball machine Ryan Schimpf is proof of that, with a career .221 BABIP as a result of his almost unprecedented 64.7% fly ball rate. Elite line-drive hitters like Miguel Cabrera and Joey Votto barely know what a .300 BABIP looks like, having spent virtually their entire careers well above that mark.

Schwarber might not have extreme batted ball tendencies in the manner of Schimpf, but it’s possible his batted ball mix is problematic in another way, one that lends itself perfectly to the shift. Per FanGraphs’ shift data, 94 of Schwarber’s 206 plate appearances have taken place with some kind of shift on. That also only measures PA that ended with a ball in play, so strikeouts, walks and home runs all aren’t counted – those represent 95 of his PA. In other words, Schwarber gets shifted a lot.

Furthermore, before Maddon finally stopped using him as the leadoff hitter, teams always had at least one opportunity per game in which there was definitely no-one on base when Schwarber was at bat, allowing them to shift with impunity.

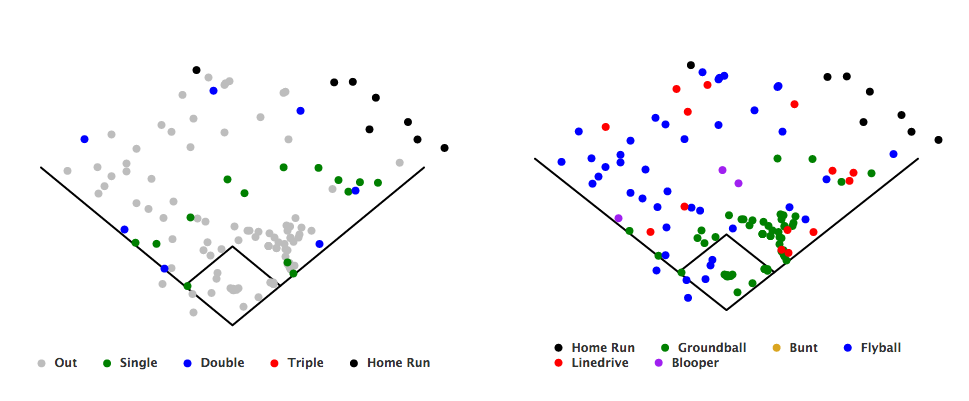

Why are teams so keen to put the shift on when Schwarber’s at the plate? Below are his hit and batted ball type spray charts for 2017, courtesy of FanGraphs:

Schwarber has been extremely predictable when it comes to setting a field for him. He hits most of his grounders into the hole between first and second base, indicated by that dense cluster of batted balls that have turned into outs – perfect for the shifted infielder. Almost all of the grounders that aren’t pulled are hit close enough to the middle of the field that the shortstop playing up the middle can turn those into outs too.

The effects of the shift are reflected in his results: a .180 batting average on ground balls this year, over 100 points lower than his mark in 2015 and over 60 below the 2016 league average of .241. In May, the 24-year-old picked up just two hits all month on ground balls. His xwOBA on grounders in 2017 is .261, compared to an actual of .166, but it’s reasonable to wonder how much we should really expect that to rise if the direction of those grounders doesn’t change. No matter how hard Schwarber hits the ball, if it’s on the ground and directly at a second baseman deep in the hole between first and second base, it’s still going to be an out. As long as that tendency continues, teams will keep shifting and well-hit grounders will keep turning into outs.

With his current approach, Schwarber actually looks fairly like the least effective version of Chris Davis: still plenty of walks and a decent amount of power, but lots of strikeouts, a terrible batting average partly as a result of those shifts, and not enough power to offset the resulting lack of production.

To make matters worse, unlike Davis, Schwarber doesn’t have a defensive position to play at which he’s actually somewhat valuable. He also can’t run well enough to beat out many of the less simple plays for the infield, further limiting that grounder BABIP. Davis certainly isn’t a terrible outcome if Schwarber can also replicate his best years, but there’s a huge amount of volatility there, and it’s directly tied to BABIP fortune and home run per fly ball rate.

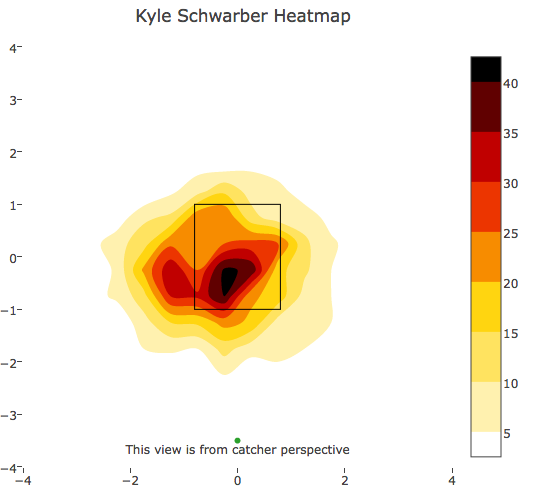

It’s easy to forget that we’re still less than 500 plate appearances into Schwarber’s career. There are plenty of adjustments he can make that will make these struggles a thing of the past. Showing the kind of power to the opposite field that he did in 2015 would certainly help. Right now, pitchers are free to pitch him away with relatively little fear that Schwarber will take the ball the other way with authority, and they have been doing so frequently, as his Statcast heatmap shows:

Many of those pitches away have still been pulled for easy ground ball outs. Even being able to force a ground ball through the hole created by the shift, or looping a line drive into left a few times would make pitchers think twice, but that isn’t something he’s been able to do so far. Saying that Schwarber should send those the other way is certainly easier than actually doing it, but it’s a change that would make him a much tougher hitter to face. He also isn’t hitting many line drives, which still turn into outs when hit directly at a defender, but would give him a better chance of avoiding the shift than grounders do.

Another way would be to take the Davis route and deliver so much power most of the time that it becomes irrelevant that many of his would-be grounder hits are taken away by the shift. Sure, the batting average will still be low, but Davis has been an extremely productive MLB hitter almost entirely on the strength of his walks and tremendous power. Finding that immense level of power that renders the shift issues moot is not easy, but Schwarber has the potential to do it.

There are lots of things Schwarber still does well. The power is still present, as demonstrated by his grand slam yesterday, and he has the discipline to take walks even when he’s struggling this badly. His luck won’t stay as bad as it did in May either, even if we might expect shifts to take more hits away from him than the average player. The fact remains that there’s a clear blueprint for how to successfully turn Schwarber into a relatively ineffective hitter, and the sooner he can shake that off, the better.

Lead photo courtesy Jake Roth—USA Today Sports