The pattern has grown beyond tedious. Flashes of brilliance tantalize, the curious cloud begins to lift, and then…it doesn’t. When Joe Maddon promised a new path for 2017, full of potential hazards, the inevitability rang true. Yet the actual difference a championship could make has caught everyone off guard.

Through nearly half a season, the Cubs’ supremely talented roster can’t seem to shake .500. Dominance giving way to mediocrity would be easier to swallow with a tangible cause, and theories have been floating since April. But weather, fatigue, injuries, even indoor bullpens (somehow), cannot quite explain players so little resembling their 2016 selves. An ill-defined theme has been cropping up in postgame rhetoric as a result: the defending world champs simply haven’t been feeling it.

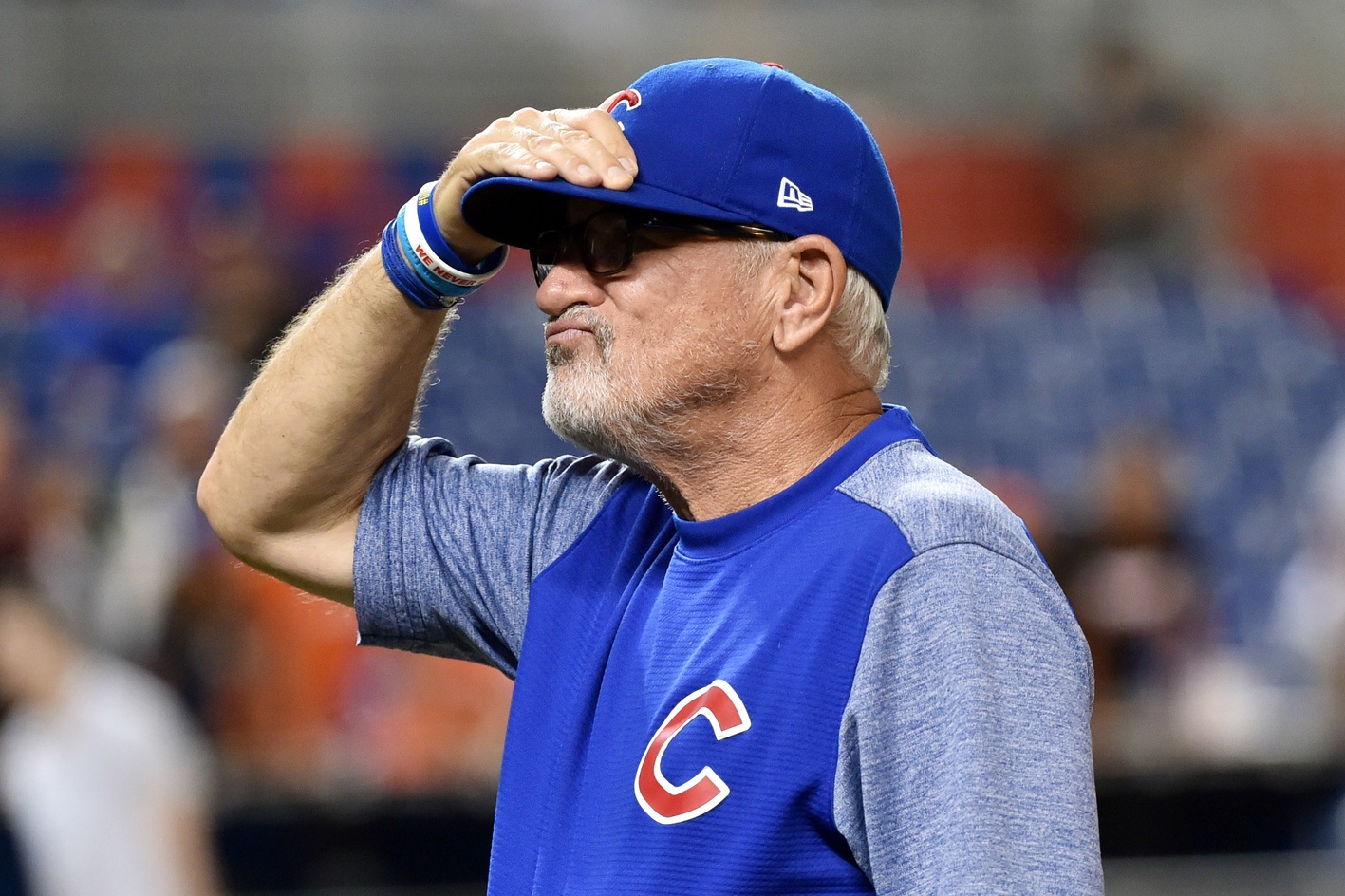

Brutal offensive numbers with runners on base? Maddon has blamed emotion: “It’s just a mindset, kind of, more than anything else with runners in scoring position. It’s playing with the middle of the field more consistently. It’s not trying to do too much. It’s not trying to be too eager. It’s an emotional moment, I’m telling you. It’s more that than something physical.”

Drop four in a row at Wrigley? Even a perpetually optimistic MVP couldn’t sugar coat it: “You go through spells where you don’t feel good. This, as a team, is probably the lowest point since I have been here.”

Upturns have been couched in similar terms. While sweeping the Cardinals after an abysmal west coast run, Maddon was talking feelings again: “The best way I can tell you or describe it is I can feel the difference in the dugout…The believability is in the dugout.” Until, of course, it wasn’t again.

Mindset, emotion, feel, believability. No one was saying ‘hangover,’ but the unwelcome signs have been there, demanding attention. Before the season began, Theo Epstein deemed any form of post-World Series hangover or complacency a “total non-issue” for his team. That assertion now seems decidedly premature.

The Cubs president was forced to officially reassess last week upon sending 2016 demigod Kyle Schwarber down to Triple-A Iowa to clear his head. Epstein chose the most palatable terminology he could in addressing his team-wide concerns:

“Obviously there’s a different dynamic with the team this year coming off winning the World Series than there was the year before. That’s just human nature. Rather than ignoring it or using it as a crutch, I think it’s important to talk about it and figure out how to conquer it…how to shift that environment so it allows us to play at our best and get really hot and have a great second half of the season.”

Epstein can call it whatever he wants, but that sounds a lot like a championship hangover persisting in late June. And while the taboo concept can never be an acceptable excuse for teams or fans (nor should it be), omitting it from discussion doesn’t make it go away.

Clearly, something has prevented the good feelings from settling in this year, and the Cubs’ remaining path will be determined by removing the obstacle or succumbing to it. Sports psychology offers theories and perspectives that can shed light on the process. And while the subject can seem annoyingly elusive, its impact on the game – and the humans that play it – is undeniable.

The idea that winning carries an emotional cost is nothing new. Bruce Ogilvie (a founding father of the sports psychology field) wrote his treatise on the rarity of repeat championships and the “peculiar psychology of winning” decades before these Cubs made history.1 Yet his description of the challenges champions face seems eerily applicable to the heroes of 2016.

Ogilvie’s profile isn’t pretty, attributing far more human messiness to athletes than fans wish to consider, but it provides valuable insight into what may be going on and addresses some common misconceptions about the hangover construct. Too often, post-championship complacency is equated to laziness, or a conscious choice to rest on proverbial laurels.

Ogilvie describes complacency as a subconscious “shift in motivational intensity,” during which the athlete may struggle to achieve the same drive or focus, but, notably, is unaware anything has changed. Both coaches and players are baffled by poor performance outcomes when the preparation, work ethic, and approach seems identical to the previous year.

An oft-repeated winter narrative was that these young Cubs, chosen in large part for their unassailable character, would be immune to complacency come spring. Ogilvie argued the psychological traits associated with top ‘character’ athletes actually make them more susceptible to a post-championship slump, not less.

According to his observations across 30 teams in various sports, those most affected tended to have “exceedingly high achievement needs, above-average emotional integration, and above-average intelligence,” combined with being “highly ambitious, emotionally mature individuals.” It’s practically a ‘That’s Cub’ checklist for player makeup.

Ogilvie explained these attributes often correspond with excellence in an underdog role. The psychology would be ideally-suited, for example, to stare down a century of losing with poise and confidence. But such players may also rely on the extra motivation of that challenge to achieve peak performance, or, as he put it, “to play with all the skill and intensity at their command.”

The 2016 Cubs may have represented the perfect 108-year curse-breakers from a mental standpoint. They were handpicked to shoulder that burden, but an uphill battle may have always been waiting on the other side. That’s no one’s fault, just human nature and the subconscious mind at work.

A dip in motivational intensity would be a significant enough hurdle all by itself, but Ogilvie was just getting warmed up. A champion’s hangover can unfortunately include a complex tapestry of emotional baggage. There is also, for instance, an altered dynamic with the fan base for players to process, the so-called, “responsibility of success.” All of the celebrations to start the next season aren’t merely distractions. They become gauges of fan expectation levels, which to the athlete feel higher than ever before.

Hence, relieving one burden can actually create a whole new cross to bear in players’ minds. Considering the pressure-filled fan-scape these young Cubs have already had to navigate, raising that bar further may finally become too much. Ogilvie theorized: “The athletes often feel as though they are on trial and are expected to exhibit excellence on demand…At some point, athletes may begin to feel they are in a no-win situation: If they lose, they incur the fans’ wrath; if they win, they’re subjected to increasingly unrealistic expectations and pressures.”

Even if this characterizes the extreme bleak example, it’s easy to imagine how the perception of increased fan expectations could translate to the always-debilitating state of ‘trying to do too much.’ In Ogilvie’s description, failure to live up to the responsibility of success can begin to feel like hero’s betrayal, which only builds more pressure from within.

Further exacerbating the fear and insecurity are new questions of confidence. According to the theory, a recent champion may also struggle with the impending bodily demands of going back-to-back: “Some athletes may doubt their ability to again pay the physical price of success…questioning their ability to recommit to playing at their former intensity.” With the regular season grind plus postseason stress so fresh in their memories, and less time than ever before to recover from it, latent self-doubt can easily creep in.

Naturally, the effects of these subconscious mechanisms come and go and vary in strength. Ogilvie said the mental shifts can take “subtle behavioral forms” that amount to a champion just not looking like himself at times. While none of this can be proven definitively, it doesn’t really need to be. The argument’s logic, combined with the Cubs’ frustrating inconsistency, paints a compelling enough picture to guess at least some of this has been clouding the repeat bid so far.

Thus, psychology’s predictions and the Cubs’ self-reporting agree: the 2017 path is harder. If the north siders can soon return to form, understanding the mental hurdle makes their potential achievements this season even more impressive. But that’s still a very big ‘if.’

Since none of the post-championship stumbling blocks operate on the level of an athlete’s awareness, identifying and combatting them is tough. Typically, they run their course and dissipate over time. With more than half the season left to play and the division well within reach, however, the Cubs need a more immediate strategy to lift the fog. Specifics on the organization’s response will never be made public, but, as the Epstein-led front office has made mental skills a particular point of pride, we can assume them to be all over it.

In his new capacity as Mental Skills Coordinator, former Cubs catcher and cult-hero John Baker indicated as much as he tried to explain the problems he’s seeing. Unsurprisingly, he echoed a number of Ogilvie’s observations, with a twenty-first century twist:

“I think that our team right now is facing the issues of dealing with what’s going on outside, what the people are saying, with the expectations. All those things are not real and they’re stories that we tell ourselves. Those stories don’t help us field the ground ball and throw it to first base or hit the ball when they throw it. So it’s all about this re-centering and refocusing process…and that takes a lot of the stress and anxiety away, because those things are usually either future concerns or they’re worrying about the past or they’re worrying about somebody else’s opinion that doesn’t matter. And with social media, and access to technology, and all the stuff that we have, it’s harder than ever…I couldn’t be prouder of the way the guys are trying to respond.”

It’s an important distinction to make from the 1990s version of pressure and expectations. The player-fan relationship has always affected the game, but Ogilvie couldn’t have imagined how far it would evolve in a generation. The pioneer left his legacy to a still-Twitterless world, after all.

The Cubs reign in the new world, where the same ‘human nature’ struggles their predecessors faced are digitally reflected and magnified in an ultra-reactive public sphere. Attitudes and outlooks are shaped in real time; highs seem higher and lows, lower. It’s no wonder teams now need professionals like Baker to provide, in his words, “non-judgmental support.”

There’s a lot more to block out these days, and more for a team mindset to overcome, but the Cubs have a history of using the challenge to their advantage. The cultural momentum that launched a championship can arguably be traced back two seasons to a Miguel Montero tweet that caught fire. From its initial tongue-in-cheek tone of surprise to ultimate understated irony, #WeAreGood captured a feeling that willed itself into reality.

But all of that emotion climaxed last November. Epstein concluded that conquering the Cubs’ 2017 ‘dynamic’ would mean confronting the negative and shifting their environment toward the positive. Right on cue, Montero stepped up to re-galvanize a movement, coining the obvious sequel, #WeAreBack.

Like the original, ‘we are back’ is powerful in its simplicity, acknowledging the struggle while claiming victory over it. If successful, belief must once again precede truth, and that’s some mind-over-matter gold.

Will it be enough to shake the peculiar pitfalls of winning the big one? Only time will tell. But for a talented young roster in search of a feeling – and themselves – it’s a start.

***

1. Ogilvie, Bruce C. “Repeat Championships: Why So Rare?” The Physician and Sportsmedicine 18, no. 12 (1990): 102-108.

Lead photo courtesy Steve Mitchell—USA Today Sports

Great piece, Leigh. I may have to keep circling back to it just to get through this season! I do get it, though. For the players to muster up the collective will and intensity over a seven-month slog after emptying the tanks just five months prior is a big ask. Not many teams can do it. Then again, baseball is weird. The prevailing fantasy has the team rope-a-doping their way through August and then catching fire in September to win the division and “find a way” through the post-season. I’d be okay with that.

Wait a minute. Wasn’t “this” the whole reason we were supposed to love Joe Maddon. Mr. Manage and Motivate the Intangibles Guy?

Asking for a friend.