If you feel moved in any way by this piece, please consider donating to United for Puerto Rico to aid America’s forgotten people in their lengthy, arduous recovery from Hurricane Maria.

On February 9th, 1995, over 23,000 fans packed themselves into the 18,000 seat Hiram Bithorn Stadium to watch Puerto Rico’s “Dream Team” take on the Dominican Republic in the final game of the Caribbean Series. Not only was the series the finest exhibition of Puerto Rico’s baseball talent, it also served as an homage to the island’s strength, resiliency, and dedication to the sport. And enrobing it all was Hiram Bithorn, Cubs pitcher and the first Puerto Rican to play Major League Baseball.

Puerto Rico adopted baseball from Cuba in the late 1890s, creating its first two professional teams in 1897, the Almendares and the Borinquen clubs. Baseball quickly became a point of pride for Puerto Rico, as two years after it was assumed into American territory, the Almendares trounced the American military team 32-18. From that point forward, Puerto Ricans wholly embraced baseball, using it as a means of connecting to the United States while retaining their own identity. Every stadium became a town hall, and every major league player took with him the hopes and dreams of this island.

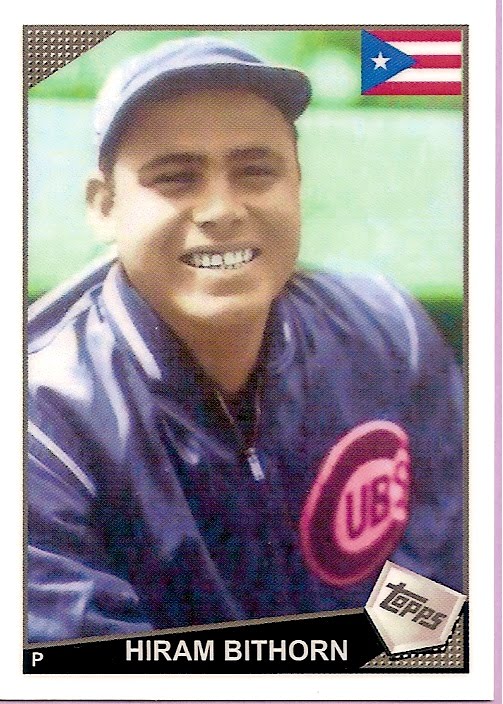

Serving as the epicenter of Puerto Rican baseball, Hiram Bithorn Stadium holds a particularly compelling place in the story of the sport, beginning with its name, derived from Hiram Bithorn, the first Puerto Rican to play major league baseball. Like many young Puerto Ricans, Bithorn grew up playing baseball, but he quickly separated himself from the pack, and all who watched identified something special in him.

His professional journey began in 1936, when he was selected by the Negro Leagues’ Newark Eagles to pitch for them in an exhibition game against the Cincinnati Reds. The 20-year-old hurler pitched seven strong innings, allowing only one run and setting the stage for his MLB career. He was soon signed to Norfolk’s B team, and over the next two seasons he progressed to the Yankees’ double-A affiliate, the Newark Bears. In each of these offseasons, he returned to Puerto Rico to play winter ball with Senatores de San Juan, where he assumed the affect ionate nickname “blanco” due to his career in the United States.1

ionate nickname “blanco” due to his career in the United States.1

In 1941, the Cubs drafted him from the Hollywood Stars. The team, struggling to find replacements for all of the players lost to both war and ineptitude, were intrigued by Bithorn’s fastball—said to be the fastest in the Pacific League— and his devastatingly tight curve. Still recovering from arm surgery, Bithorn’s inaugural season with the Cubs in 1942 was a bit of a disappointment. Though he logged 171 and 1/3 innings, he allowed 191 hits and 81 walks, while the struggling offense of the sixth-place Cubs managed to get him only six wins.

His mediocre performance, though, was the least of his concerns. Rumors began swirling that he was actually mulatto, contrary to the report published by the Cubs that he was of Dutch and Spanish heritage. It had become acceptable for Latino players to enter the major leagues as long as their skin was not too dark, and these reports threatened to end his career. Additionally, many players, executives, and writers looked for ways to make these players’ existence as uncomfortable as possible. Bithorn was routinely heckled by opposing players, the culmination of which occurred in one game against the Brooklyn Dodgers who had become known as the “jokesters” of the league. The typically calm, quiet Birthorn became so overwhelmed by the vociferousness of the comments that he fired a ball into their dugout, aimed at Leo Durocher. Naturally, the Dodgers received no punishment while the league fined Bithorn $25.2

As his arm healed and he became comfortable with his teammates the following season, Bithorn improved greatly, throwing 249 and 2/3 innings and allowing only two more earned runs than the previous season, notching 18 victories and leading the league with seven shutouts. Unfortunately, the US military refused to extend his deferment, and he was assigned to the U.S. navy stationed in Puerto Rico. There, he routinely played in the base’s baseball games, which drew crowds of over 8,000 and donated all proceeds to the Red Cross and various other war relief efforts.3

He spent two seasons on the base, returning to the Cubs in in the middle of the 1945 season, but he did not play one single game for the World Series-bound team. He thus triumphantly returned to the major leagues in 1946, slightly heftier and diminished in skill. Only pitching 86 and 2/3 innings, he had the worst year of his professional career, much to the disappointment of those rooting for him back home. The following season, the Cubs let him go, and though there was not much interest in a mediocre pitcher from Puerto Rico, he eventually was signed by the White Sox, where he only threw two innings before suffering a career-ending arm injury.

Ever resolute, Bithorn made several attempts to rehab his career with various teams in Mexico, but nothing took, and so he switched to coaching, determined to remain involved in baseball in whatever capacity was open to him. In 1951, he returned to Mexico, traveling to Mexico City to visit his grandmother for New Years. Like his many failed rehab attempts, the initial promise of this journey gave way to devastation. Somewhere along Federal Highway 45, Bithorn got into a scuffle with his driving mate and was eventually killed. Under sketchy circumstances, at the age of 35, the Puerto Rican hero met his end. His funeral took place ten days later, and over 6,000 shocked Puerto Ricans gathered at the island’s beloved Sixto Escobar Stadium to lay Bithorn to rest.4

Though a police officer was convicted of his homicide and sentenced to eight years in prison, the events of his death remain a mystery, and in the years following it, it seemed like every Puerto Rican developed their own conspiracy theory concerning their beloved figure. The entire country became wrapped up in his death, but they also voraciously celebrated his life, the culmination of which occurred in 1962, when they named the island’s new 18,000 seat baseball stadium after him. And on October 24th, the stadium filled to open the winter ball season, amassing the largest baseball crowd to that date in Puerto Rico’s history.

Bithorn’s memory lives on in that stadium, and it enveloped every moment of that 1995 Caribbean Series, which boasted the highest number of MLB players to ever appear in the series. The Puerto Rican “Dream Team” consisted of a number of MLBers, each of whom owes their career to Bithorn: Roberto Alomar, Bernie Williams, Juan González, Edgar Martínez, Carlos Baerga, Rubén Sierra, Carlos Delgado, Roberto Hernández, Carmelo Martínez, and Ricky Bones, among others. Ordinarily, these players would have been occupied with preparing for Spring Training, but the 1994 strike drove them to play winter ball, freeing them up for this series, the 25th of its kind.

Eschewing the standard Senatores uniform, the team instead, for the first time in Caribbean Series history, wore uniforms emblazoned on the front with “Puerto Rico.” For many, it was their first opportunity to so publicly represent their home, and they did so with pride. Surrounded by the colors of the flag and the exuberant cheers of their families, the team swept away its competition, outscoring them in the six-game series 49-15, putting on perhaps the most dominant display of baseball ever witnessed.5

During those six days, Puerto Rico’s first national team overwhelmed Hiram Bithorn Stadium with pride, forcing it to spill out into the streets and steam onto the shores of America. It connected Puerto Rico with American sports fans, urging both the NBA and MLB to host a number of exhibition games at Hiram Bithorn in the coming decades. That championship night, February 9th, 1995, was the beginning of Hiram Bithorn Stadium’s true embodiment of the man for whom it was named. It housed the skill, passion, and dedication that Bithorn tirelessly worked into the fabric of Puerto Rican baseball, and it displayed these virtues to the world.

1 https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/0ebf1b32

2 The Indianapolis Star, July 17, 1942.

3 Nick C. Wilson. Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), 149.

4 Bloomington Pantagraph, January 14, 1952.

5 Lou Hernandez, “Chronology of Latin Americans in Baseball, 1871–2015,” (North Caroline: McFarlane, 2016), 129.