Chris Bosio will be plying his pitcher whispering craft in a city other than Chicago next year, and it’s sort of the bullpen’s fault.

Before walking the entirety of the Washington Nationals and Los Angeles Dodgers’ rosters, the Cubs bullpen was solid. They were one of the better relief units in the league, actually, ranking sixth in ERA, sixth in left-on-base percentage, ninth in groundball rate, sixth in strikeout rate, third in batting average against, fourth in contact rate, and eighth in soft contact. Overall, the bullpen was probably the fifth- or sixth-best in the majors, bested by Cleveland, the Yankees, the Red Sox, and the Dodgers.

But the walks—the struggles that the Cubs ran into with their bullpen in the playoffs were not new, nor were they surprising. All season, the bullpen (in its many iterations) had lost and regained and lost its command, eventually posting the worst walk percentage in the majors, at 11.2 percent. For context, the league average this season was 9.2 percent, the highest since 2011, and the only Cubs relievers to finish the season below that threshold were Hector Rondon, Brian Duensing, and Koji Uehara. The rest of the relief corps—Wade Davis, Pedro Strop, Carl Edwards, Jr., Mike Montgomery, Justin Grimm, and Justin Wilson—all topped the 9.2 mark, an untenable situation that was bound to result in wild swings in performance in the crucible of the playoffs.

In the two series the Cubs played versus Washington and L.A., Davis walked six batters to only five hits (two home runs); Edwards walked six and allowed only two hits (one home run); Duensing walked four and allowed a single hit; and Strop issued three bases on balls to only one hit. Of the 11 pitchers the Cubs used in the two series, only Rondon, Montgomery, Kyle Hendricks, Jose Quintana, and John Lackey allowed more hits than walks. Montgomery and Rondon were the only Cubs to take a beating from opposing hitters, and Montgomery’s many hits came largely in mop-up duty.

These stats convey the magnitude of the problem. Of the other top bullpens, no team walked close to the amount of batters of the Cubs’ group, and only the Yankees walked more than league average, at 10 percent. The Cubs are an outlier, and it is clear that being exceptional in this regard is a significant hurdle to sustained, consistent success in relief. The suspicion is that Bosio did little to dissuade Cubs pitchers from walking hitters, evinced by the 10.1 percent walk rate the bullpen has sported since Bosio came aboard in 2012. Even as the Cubs have improved their ‘pen dramatically from the woeful state it was in when Bosio was hired, and even as the Cubs’ strikeout rates climbed and opponents’ batting averages dropped, the walk rate remained.

With Bosio gone, and with former Rays’ pitching coach Jim Hickey rumored to be the favorite for the vacant position, the Cubs have an opportunity to remake their bullpen philosophy. In terms of personnel, the 2018 bullpen might not be too much different: the incumbents are Edwards, Strop, Rondon, Montgomery, Wilson, and Grimm. There is a possibility that the Cubs do not tender Grimm a contract, and a smaller possibility that they cut ties with Wilson, who was, simply put, very bad after arriving in Chicago at the trade deadline. The latter pitcher is the second-most important circumstantial strike against Bosio—Wilson lost his groove when he left Detroit and never found it, eventually resulting in him being dropped from the NLCS roster. Such a dramatic change does not reflect well on the pitching coach, but might offer a glimmer of hope that a new instructor could help right Wilson for 2018.

The Cubs will add more arms to this group, and they will seriously consider re-signing Davis to close games for the next few years, but it’s worth asking the question: can this group improve on its walk rates in 2018 and beyond?

The unexciting, but probably correct answer is yes, but not by much. In order to come to a satisfying conclusion, one needs to consider the track records of each pitcher, league-wide trends in walk rates and the strike zone, the specific factors that led to each pitchers’ poor 2017 numbers, and Hickey’s personal philosophy regarding walks. That’s… a lot of work, but we can begin the process by taking a quick look at the three pitchers most likely to garner significant innings next season: Edwards, Strop, and Rondon.

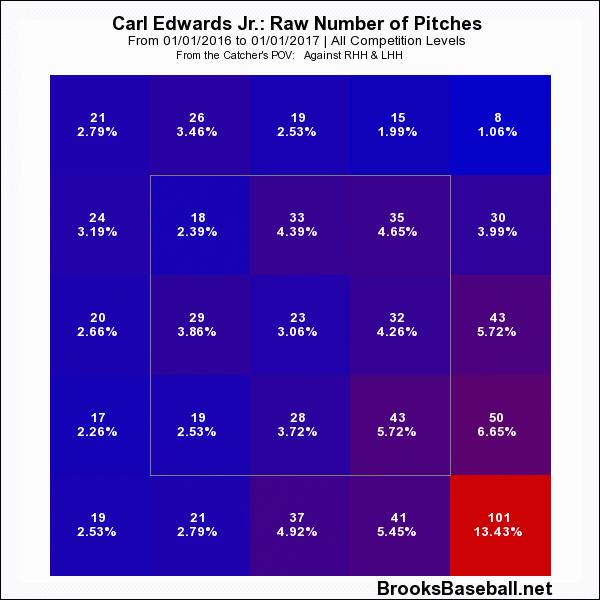

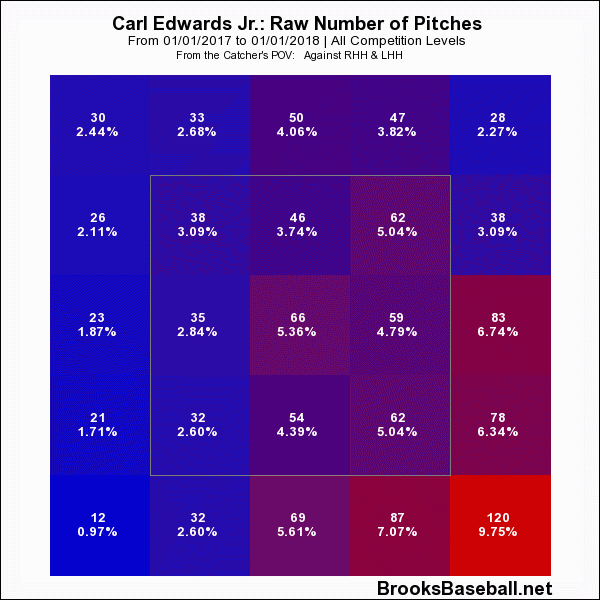

We begin with Edwards, who is the most difficult to pin down. The slender righty walked 14.5 percent of the 262 hitters he faced in 2017, a four-percent jump from his 10.1 mark in 2016. Edwards faced almost exactly twice as many major-league hitters this past season as he did the previous year, and, while Edwards maintained his stratospheric strikeout numbers, there were times at which even Edwards didn’t know where his fastball was going to end up. In the minors, Edwards’s walk rates were frequently between 15 and 18 percent, unsustainable numbers for any pitcher. One glance at Edwards’s zone profiles from 2016 and 2017 reveal his fastball’s tendency to wander:

Edwards displayed a knack for finding the bottom of the zone in 2016, and generally stayed out of the heart of the plate. In 2017, Edwards’s pitches are smattered across the first-base side of the plate—he threw many more high fastballs (not necessarily a bad idea for someone with his lively fastball), but also caught much more of the plate. Hitters have shown no aptitude for hitting Edwards’s pitches, and so throwing more strikes would likely serve Edwards well, but I have a hunch that many of the pitches catching the middle of the plate are the result of trying to throw a strike when behind in the count, after unleashing a few not-so-close balls. So, although Edwards’s history doesn’t indicate a high likelihood of lowering his walk rate, a return to 2016’s better located fastballs is possible.

2016’s version of Strop also submitted a career-low walk rate, an even eight percent, sandwiched by several 10 percent seasons. Strop also struck out a career-high 32.1 percent of hitters in the Cubs’ World Series campaign, and allowed a career-low batting average to opposing hitters. In 2017, Strop was one of the Cubs’ most consistent relievers, but the righty experienced a slight dip in strikeouts with his increase in walks. Could Strop regain last season’s form?

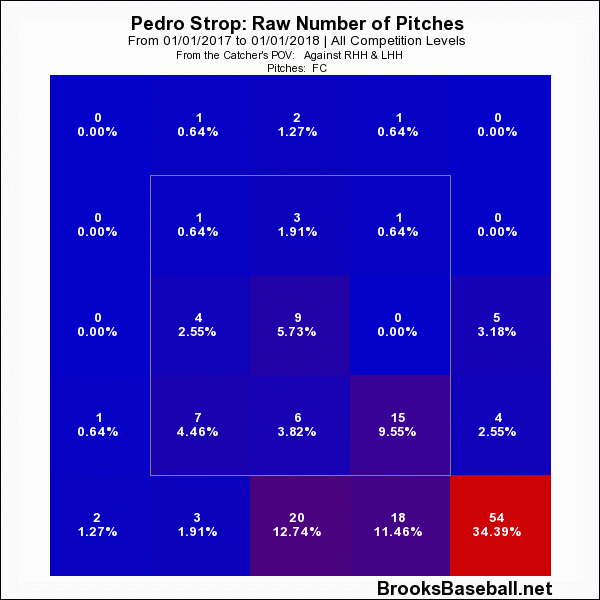

I harbor a bit more optimism regarding Strop than I do with Edwards. Strop found an extra tick or two of velocity among his pitches in 2017, averaging 96 mph with his fastball, 85 with his slider, and 89 with his newly-deployed cutter. Strop’s walk rates were over two percentage points higher in the second half of the season, when he was experimenting with his new cutter, so there’s a high likelihood that the creatively lidded righty had difficulty commanding his new pitch.

That’s not a bad spot for the pitch, which he primarily used as an out pitch versus lefties but sprinkled in equally in all counts versus righties. More time with the cutter, and possibly a tweaked game plan in how he uses it, might help Strop take a step forward as a pitcher in 2018, and hopefully cut down on walks in the process.

Our final pitcher, Rondon, is the easiest to analyze. Rondon doubled his walk rate from 2016 to 2017, leaping from 4.0 to 8.4 percent, while striking out hitters at a career high rate. Rondon experienced an injury in September, as an MRI revealed bone chips in his elbow, but from August to the end of the season the righty walked far fewer hitters than he had from April through July. In 11 ⅓ innings from August 19 to the end of the season, Rondon didn’t walk a single hitter, with nine appearances coming before his injury and four after.

Rondon has been the Cubs’ best pitcher in terms of walk rate over the past several seasons, posting marks of 5.9, 5.3, 4.0, and 8.4 percent from 2014-2017, and there should be little concern that Rondon’s 2017 will be his new normal. A clean bill of health, a more stable spot in the bullpen, and a few months off will likely do more for Rondon’s command than any mid-season tweaks.

Overall, the prognosis is not dire. If one or two of the Cubs’ top pen arms improves, then there is a good chance that 2017’s unsightly walk rate will return to more acceptable levels in 2018. To wit: Wade Davis and Justin Wilson both posted career-high walk rates as relievers this past season. If Davis returns, and if Wilson finds even a modicum of his Detroit self, then there is cause for optimism. Jim Hickey, or another pitching coach, won’t even have to do much.

Lead photo courtesy Jim Young—USA Today Sports