Three years after the full professionalization of the 1867 Cincinnati Red Stockings, Chicago created its first professional baseball team, The Chicago Base Ball Club, quickly dubbed the Chicago White Stockings. The team fared well in its first two years, but was forced to quit the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players at the end of the 1871 season due to the Great Chicago Fire that had destroyed much of the city, including the team’s ballpark. After assisting in the city’s rebuilding process, the White Stockings returned to professional play in 1874. In 1875, anticipating the creation of the National League, team owner William Hulbert acquired Boston ace Albert Spalding and Philadelphia first baseman Adrian Anson, two moves that set the tone for the team’s first four years of National League baseball.

Setting the Table

Throughout his years as a baseball team owner, Hulbert, a wealthy member of the Chicago Board of Trade, had studied the National Association of Base Ball players, determining it to possess several faults. He notoriously believed no business deal was too rotten to not benefit from his involvement, and so he set about to create a more owner-centric league that could better control the players’ actions, limiting drinking, rowdiness, and game-fixing, while increasing economic capital through the presentation of a gentleman’s league. With the assistance of seven other owners, Hulbert birthed the National League, immediately doubling ticket prices, banning Sunday baseball, and prohibiting the selling of alcohol. This new professional baseball league would be run like a business, despite the players’ insistence that it was a game, tapping into the rising Christian sentiments in the country.1

Determined to make Chicago America’s premier baseball city, Hulbert poured more money into the team, drawing away Spalding, Anson, and a number of other established players from their teams with the promise of greatly increased salaries. Due to the strength of these players, the team finished first in the 1876 inaugural season, with a winning percentage of .788. The high-powered offense, led by future Hall of Famer Deacon White, three-time batting champion Ross Barnes, and Anson, scored almost 10 runs per game, 3.3 more than the second-place Hartford Dark Blues. Spalding held his own on the mound, pitching in all but 11 of the team’s games, continuing the success he had in Philadelphia. For vast stretches of the season, the team truly looked unbeatable.

Unfortunately, perception does not fully define reality, and the indestructible team quickly fell apart. Deacon White decided to return to Boston after just one season with Chicago, leaving a hole in the lineup at catcher that the team unsuccessfully tried to fill with Cal McVey. Spalding, the team’s manager, also needed a replacement, as he had moved toward the business side of baseball, first in organizing the breakup of the International Association to eliminate National League competition, then as a sporting goods magnate to capitalize on his introduction of the glove.2 As his replacement, the team acquired from St. Louis the 1876 ERA title holder, George Bradley. However, Bradley and the revamped lineup were disappointed, putting the roster into flux for much of the season and establishing trends that would continue for the rest of the decade, wherein the Cubs finished 5th in ‘77 and 4th in both ‘78 and ‘79.

A Game of Trends

Perhaps the greatest example of the 1870s Chicago teams occurred in an 1878 exhibition game against the Buffalo Bisons of the Independent League. Exhibition games for all National League teams were fairly common ways of procuring revenue and showcasing roster turnover in these early years, but William Hulbert took it to another level. He arranged exhibition games against whatever teams were willing to participate, taking his team into Ontario and throughout the upper-midwest, as well as to other NL cities during October and March of each year.

Hulbert agreed to play Buffalo to test his team against a prospective addition to the NL. Setting the game for August 4th, Hulbert hoped to give his team a boost against likely less skilled competition at a time in the season when the team had historically struggled the most. But though the White Stockings won the game, it was not the morale boost it was envisioned to be.

for August 4th, Hulbert hoped to give his team a boost against likely less skilled competition at a time in the season when the team had historically struggled the most. But though the White Stockings won the game, it was not the morale boost it was envisioned to be.

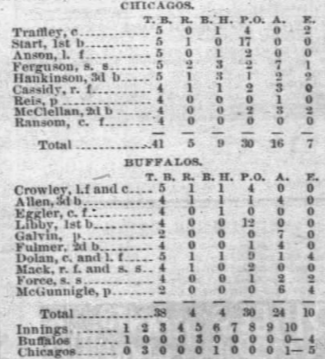

Buffalo jumped out to an early 1-0 lead in the first inning when shortstop Bob Ferguson threw away the ball, allowing Buffalo’s third baseman, Allen, to reach first. A passed ball, stolen base, and groundout brought him home. Chicago gained the lead in the second inning, scoring three runs on a Ferguson double and a calamity of errors by just about every Buffalo player that resulted in the ball being stuck under first base seats. Error assignment in these years was always a dubious endeavor, but it is probable that Buffalo deserved the three errors it received on this play.3

Through the first two innings, though neither team looked great, it seemed obvious that Chicago had the far superior talent. And then rookie pitcher Laurie Reis gave up three straight hits and muffed a pop fly, allowing Buffalo to gain a 4-3 lead. The 19-year-old Reis would make four league starts for the team that season, as well as several other exhibition starts, filling in on occasion for Terry Larkin, a pitcher acquired from Hartford at the beginning of the season. Larkin pitched well that season, but had some minor arm soreness that flared up the following season, forcing him to be shut down for the final two months of 1879. Though promising, Reis, in his second season with the team, did not produce the performance Hulbert hoped for, and this 1878 season would be his last in professional baseball. Chicago fielded three excellent pitchers during these first four seasons, but the team ultimately lacked stability and longevity in the form of young, sturdy arms.

The White Stockings eventually tied the exhibition game in the 6th inning on back-to-back doubles by Ferguson and third baseman Frank Hankinson. In his only season with Chicago, Ferguson led the league in OBP, continuing the offensive excellence from the shortstop position begun by John Peters. Hankinson, on the other hand, rarely contributed offensively. He had been brought in to replace Anson at third base after Anson transitioned to the outfield to help replace the offensively inadequate 1877 trio of Dave Eggler, John Glenn, and Paul Hines. What little offensive skill Hankinson had usually manifested itself in the form of a double, making him the quintessential Chicago player of the late 1870s, in which each team was mediocre offensively but finished no lower than second in doubles hit.

It took 10 innings for the White Stockings to beat the Bisons, with hit leader Joe Start scoring on a Ferguson single. Though the team started the month with a victory, it counted for little. The team won only four games in the final two months of the season, slipping from second in the league to fourth. Evoking the trends of these ‘70s teams, this game dug up more questions than answers, most of which would be haphazardly and incorrectly answered in the offseason. Despite a marked improvement in record, finishing over .500 for the first time in three seasons, the 1979 team succumbed to a second-half collapse brought on by poor pitching and questionable defense.

The decade started out strongly for the White Stockings, but the success was fleeting, and despite Hulbert’s best efforts, the team could not establish itself as the baseball powerhouse he hoped the acquisition of Spalding and Anson would create. Each team looked far different from the previous one, and many pilfered players returned to their original teams after one or two seasons in Chicago, leaving Hulbert scrambling to plug in various holes. If the 1880s were to be different, Hulbert would need to scour the area for young, reliable talent and make Chicago a team players were eager to play for.

1“INTRODUCTION: The Chicago Cubs: From Early Excellence to the Golden Age to That Darn Goat.” In Before the Curse: The Chicago Cubs’ Glory Years, 1870-1945, edited by Roberts Randy and Cunningham Carson, (University of Illinois Press, 2012)1-10.

2Chicago Tribune, December 23, 1877.

3The Buffalo Commercial, August 5, 1878.