Ernie Banks and Cap Anson are the Jedi Master and Sith Lord of Cubs legends. Or, if you prefer another universe: Thor and Loki. If you were to cast a movie about this franchise, the two of them would most likely be played by Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner-era Sidney Poitier and the first result of any Youtube search for “Mel Gibson.”

While their present-day reputations could not be more polar opposites, that was not always the case. In fact, within their respective eras they were both hailed as icons of the Chicago National League Ballclub and upheld as model figures of the entire sport.

In retrospect, of course, the one thing for which Anson is remembered is his virulent racism which reared its head numerous times throughout his career. If he is recalled today, it’s for episodes such as his threats to refuse to take the field against Moses Fleetwood Walker’s Toledo ballclub and his abuse of White Stockings mascot Clarence Duvall much more so than for being the first player to collect 3000 hits or all of the pennants he won managing Chicago. Basically, most of us know Anson as what would happen if Curt Schilling’s Twitter account grew its own person.

But in his era where such racism was much less likely to stand out, and when many actually believed Anson was protecting the game’s legitimacy with his racist intransigence, it was those same hitting and managing skills that took all the focus and earned him notoriety throughout the country. No less an authority than Anson’s Hall of Fame plaque proclaimed him the “Greatest hitter and greatest National League player-manager of [the] 19th century.” Throughout his career, baseball writers proffered him accolades: “Personally, Anson is a splendid fellow, dignified and honest, and a great credit to the game.”1 This tribute was published in the Chicago Tribune and presumably also appeared in the most popular periodical of the era: Wrong Side of History Magazine.

Cap Anson was the first superstar and face of the Chicago club for almost the entirety of their 19th century existence. Of course, his fame and place in fans’ hearts would be eclipsed many times as the franchise staggered through the 20th—most prominently by a man who went on to become known as Mr. Cub.

I trust that you don’t need me to tell you the many ways that Ernie Banks was the personification of human awesomeness.

Now if you’ve ever spent time in Chicago, you know that there’s one thing this city does well: elevating its sports heroes beyond any sense of proportion or rationality. (The preceding sentence is brought to you by Ditka’s Kick Ass Wine.) So it should come as no surprise that when these baseball superstars were lifted up to the heights of the city’s athletic pantheon, Chicago power brokers wanted to associate themselves with their popularity and take advantage of it.

Which is how the legacies of Banks and Anson became intertwined in the most unusual way possible: as the two most prominent Cubs players to run for city office. And as tends to happen whenever Chicago politics are discussed, the history of their respective candidacies revealed a lot about how race and the city’s governmental machine played outsized roles in their respective fates.

Anson decided to enter the political scene for reasons that have become disconcertingly familiar: he was famous and bored. His baseball career with Chicago had ended poorly: as Mary Craig recently detailed, his final years were a toxic mixture of declining skills, paranoid feuds with the players he managed, and bizarre racist grudges with the Irishmen on his roster that were straight out of a 1920s Itchy & Scratchy cartoon.

His post playing days were even more scattershot and marked by failure. Aborted attempts to purchase his former Colts squad and found a Chicago-based team in the new American Association bookended an embarrassing one month stint as manager of the Giants. The only successful ventures Anson experienced after hanging up his spikes involved putting his name on a billiard hall and a bowling alley—not exactly a dignified post-career fate for one of the most well-known players in the land.

While his businesses somewhat satisfied his competitive instincts, neither offered the rush of fame that he experienced as a baseball star. Despite these post-career missteps, Anson’s name was still indelibly associated with the pennant winning White Stockings of the 1880s and as such, it still carried quite a bit of influence in Chicago. With that in mind, a friend named Tom Barrett asked Anson to make speeches on his behalf during a 1902 run for sheriff.

The positive reception he received these events was what Anson had been missing since his release from baseball four years earlier. It planted a seed in his mind and he decided to explore this new avenue further in order to keep his name in the public eye. At the same time, the Chicago Democratic Party also noticed the adulation surrounding his public appearances and, as political parties have been known to do from time to time, decided that they might want to associate themselves with a man best known for winning.

While you could never say that Ernie Banks and winning went hand in hand, he was certainly celebrated just as highly in his time for brilliant performance in the face of insurmountable odds. Which was probably why some early 1960s political consultant must have thought, “Hey, let’s run him as a Republican against a candidate backed by Mayor Daley!”

If you need a baseball metaphor, it was like going up against the Sandy Koufax of Mayors who would have definitely called Sandy Koufax an anti-Semitic slur.

By 1963, Banks was well established as the only bright spot on a seemingly never ending series of godawful Cubs teams and as the most magnetic public figure in the Chicago baseball landscape. And it was this popularity that local Republicans looked to tap into when an aide to Senator Everett Dirksen (!) reached out to Banks to persuade him to run for Alderman of Chicago’s Eighth Ward, part of the Chatham neighborhood where Banks lived at the time (and it says everything about how entrenched Chicago segregation was that even when an African American celebrity on the level of Ernie Banks worked at Wrigley Field, he still had to make his residence off of 82nd Street on the South Side).

In the early sixties, Chatham’s black population was increasing rapidly, with African American residents making up approximately 45 percent of the voting base.2 However, the eighth ward was still represented by incumbent Alderman James A. Condon, a white man handpicked by Richard J. Daley. According to the Chicago Reader’s Ben Joravsky, Daley “had a formula for racially changing wards: he stayed with the white flunky till the ward was almost 100 percent black. Then he brought in a black flunky.”

Or, as it’s more commonly known: “Chicago-style diversity.”

So essentially, the Republicans saw that, with the changing racial makeup of the neighborhood, there was a long-shot possibility that they might be able to get the jump on Daley by nominating an African American to represent it at City Hall. And for a brief moment, they decided to further their cause by recruiting one of the most popular African Americans in Chicago.

It was a pretty cynical move meant to either gain the GOP black voters or to take them away from Daley’s candidate—essentially saying, “Before Hizzoner exploits a black politician, let’s pick one ourselves!” Not only did Ernie have no experience in public service whatsoever, he was still very much an active player. Indeed, the 37 home runs and 3.7 WARP Banks amassed in 1962 were more than the rest of the entire Chicago City Council combined.

So, this was cynical but not exactly unprecedented, even among the relatively small subcategory of “Cubs who ran for office.” Indeed, if you went back a few decades, you’d see that the main reason that the Chicago Democratic Party of 1905 decided to nominate Cap Anson for city clerk was that “the party… counted on Anson to draw voters to the other men on the Democratic slate.”3

Taking advantage of the curiosity factor surrounding an unqualified celebrity for purely partisan purposes? Thankfully, these were the only two instances of this phenomenon in the history of American politics and it never happened again.

Sigh.

Here is where the two Hall of Famers’ political fates diverged, and the role of Chicago machine-style politics had a great deal to do with it. As mentioned, Anson had the blessing of the Democratic establishment supporting his candidacy and “the local party bosses set him on a tour of the city, giving speeches almost every day in support of the citywide Democratic ticket, headed by mayoral candidate Edward Dunne.”4

It was a notably corrupt era in Chicago politics–even for a city notable for the constancy of its corruption. Anson’s political career overlapped with those of notorious Chicago alderman “Bathhouse John” Coughlin and Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna, who presided over the Gemorrah-like First Ward Balls where the day’s prominent Democratic figures rubbed elbows (and other parts of the anatomy) with a procession of sex workers, pimps, and gamblers.

Yet it was also a time where the Democrats did not have the ironclad grip on city government that they would later claim. Indeed, Chicago’s mayorship had been in Republican control as recently as eight years prior. And with incumbent Mayor Carter Harrison Jr. (who himself had handed out favors and jobs for his machine cronies even under the guise of a reformer) leaving office to pursue a presidential nomination, it certainly helped the Democrats to surround Dunne with figures who Chicagoans already held in high esteem.

Anson knew how to play that game and was just the kind of public figure the machine could bend for its own purposes. As a player known for his disdain of gambling and alcohol, he also offered the Democrats a helpful contrast to the bacchanalian exploits of Coughlin and Kenna for any potential Chicago voters concerned with morality—of which there were at least twelve.

On the other hand, Banks was almost immediately stabbed in the back by the GOP. After he arrived in Chicago from a vacation to begin his campaign, he discovered that the party establishment had suddenly decided to throw its support behind someone named Gerald Gibbons, who had properly kissed the ring in the traditional Chicago way by working as a precinct captain and for the Illinois Young Republicans.

As you would have expected, this setback completely deflated Banks’ enthusiasm and he announced his withdrawal from the race with his trademark phrase: “Life sucks.” He then spent the rest of his days eating three meals a day at The Cheesecake Factory and writing lyrics for Leonard Cohen.

Or not. Like everything else that his time with the Cubs had prepared him for, Banks absorbed the temporary defeat and redoubled his efforts, noting that “Politics is a strange business. They can strike you out before you get a turn at bat… I’m in this with or without the support of the Republican Eighth Ward organization. I intend to win.”5

And Ernie proceeded to pour his heart into running as an independent, averaging four speeches per day in the two months of his campaign. While there was nothing he could do to make up for his lack of experience, he made it clear that his candidacy had a message. As you might expect in an early ’60s neighborhood whose racial makeup was rapidly changing, Ernie’s “main stated goal was to combat juvenile delinquency,” telling the media that he wanted “to do anything in his power to help youth.”6

Not surprisingly, Banks thought that investing and promoting “youth athletics” would be the best strategy to achieve this goal—in contrast to the more draconian Condon who was known for “the drafting of legislation that increased penalties for the sale of narcotics.” He further promised that he would field a “trained staff to handle ward matters” once the baseball season got underway. Considering the Cubs were still in the midst of the Colleges of Coaches era, Elvin Tappe and Vedie Himsl were probably available.

All of that sounded typical of Banks’ character. And by coincidence, Cap Anson campaigned on a racial message too. Specifically: an early 20th century fear among whites known as “race suicide”—paranoia that white families were having fewer children than families of color, and would eventually lose control over America.

So based on the messages of both players, who do you think ended up winning his race for public office?

Considering [broad hand gesture] all of American history, that officially counts as a rhetorical question.

When their respective election returns came in, Anson easily won by 24,000 votes as part of a Democratic sweep. Banks, meanwhile, finished in third place behind the Democratic flunky and the Republican flunky. And based on what happened afterwards, there’s only one conclusion to be drawn…

Ernie was better off.

Once Anson assumed the office of city clerk, he embarked on enacting the agenda that he had long been planning for his time in a career of public service. Said agenda read in its entirety:

1. Position himself to run for sheriff

In yet another longstanding Chicago tradition, Anson’s only concern as clerk was doing whatever he could to move up the ranks in city government, to the point where he approached every other aspect of his job with the most laissez-faire attitude possible. This was especially problematic when he ran up against the single greatest Chicago tradition of them all: city workers collecting a paycheck and not showing up to work.

(Let me pause here to file a petition to rename the Department of Streets & Sanitation after Todd Hundley.)

This abuse of the system got so bad under Anson’s watch that he was eventually summoned before the Chicago Civil Service Commission to explain his inaction in the face of it. When the Commission threatened to override his authority and take the matter into its own hands, the former baseball hero’s response was one for the ages:

“Won’t you let me know in advance what you intend to do? I would like to be able to get in ahead of any action you many intend to take by taking some other action myself.”7

Jerry Seinfeld Voice: And you wanted to be my sheriff…

When word of this meeting got out, Anson’s public humiliation was complete. The Tribune put the final nail in his political coffin, editorializing, “When an elective official’s eagerness for some other elective office is of the sort which makes him a coward in his present office, that cowardice is not a good qualification for another job.”8

After serving out his term as clerk, a chastened Anson finished in last place in the race for sheriff at the 1906 Chicago Democratic Party nominating convention. His political career was finished almost as soon as it started and he moved on to an aimless retirement of semipro baseball and further financial distress.

While Anson clearly benefited from his whiteness and knew how to play the networking game in politics much better than his fellow Chicago baseball great, his political victory did nothing to make his legacy look any better in comparison with Banks’. Furthermore, once Ernie’s playing days were over, he found ways to enter public service that allowed him to actually serve the public, joining the boards of organizations like the Glenwood Home for Boys, Woodlawn Boys Club, Chicago Rehabilitation Institute, and Big Brothers Big Sisters.

It was clear that when it came to building a legacy in the city of Chicago, Mr. Cub had emerged a winner. When asked late in life what goals he still had, Banks repeatedly mentioned that he wanted to win a Nobel Peace Prize. It was invariably greeted with good natured rolled eyes and a sense that this was Ernie being Ernie (“Israel & Palestine will get along great in 2008!”). As expected, he fell short of this ambitious goal.

It turned out, though, that the Presidential of Freedom was a pretty nice consolation prize. Not bad for someone who couldn’t even get elected alderman.

NOTES:

1. Fleitz, David L. Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball. McFarland, 2005. 263.

2. Wilson, Doug. “When Ernie Banks Ran for Alderman.” http://dougwilsonbaseball.blogspot.com/2015/05/when-ernie-banks-ran-for-alderman.html

3. Fleitz, 286.

4. Ibid.

5. Joravsky, Ben. “The Time Mr. Cub Ran for Alderman.” Chicago Reader. https://www.chicagoreader.com/Bleader/archives/2015/01/28/the-time-mr-cub-ran-for-alderman

6. Wilson, “When Ernie Banks Ran for Alderman.”

7. Fleitz, 289.

8. Fleitz, 290.

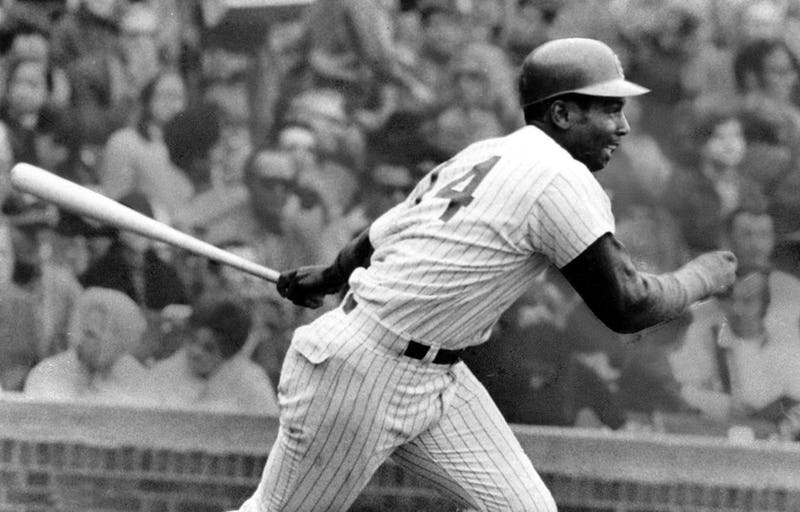

Lead photo courtesy Chicago Tribune