It is some evening in late October, and for Tyler Chatwood, it is the best of times.

After pitching meaningful innings in some game in the 2018 World Series, he now sits, surrounded by his new teammates, embraced by a new city. Chatwood reflects.

How did he get here?

When the Cubs came calling in early December, he has to admit, even he was a bit surprised. Jake Arrieta, Shohei Otani, Yu Darvish, Lance Lynn, Alex Cobb… all quality arms, still there for the taking, and the Cubs wanted him, a guy with more Tommy John surgeries than wins above replacement on his ledger. A guy with the highest walk rate in Major League Baseball over the past two seasons. A guy who had never, not once, even sniffed a league average strikeout rate. But this is 2018, the age of wisdom as far as baseball analytics go, and surface numbers, we know in this enlightened age, don’t always tell the whole story. He knew this, and he was eager to prove it.

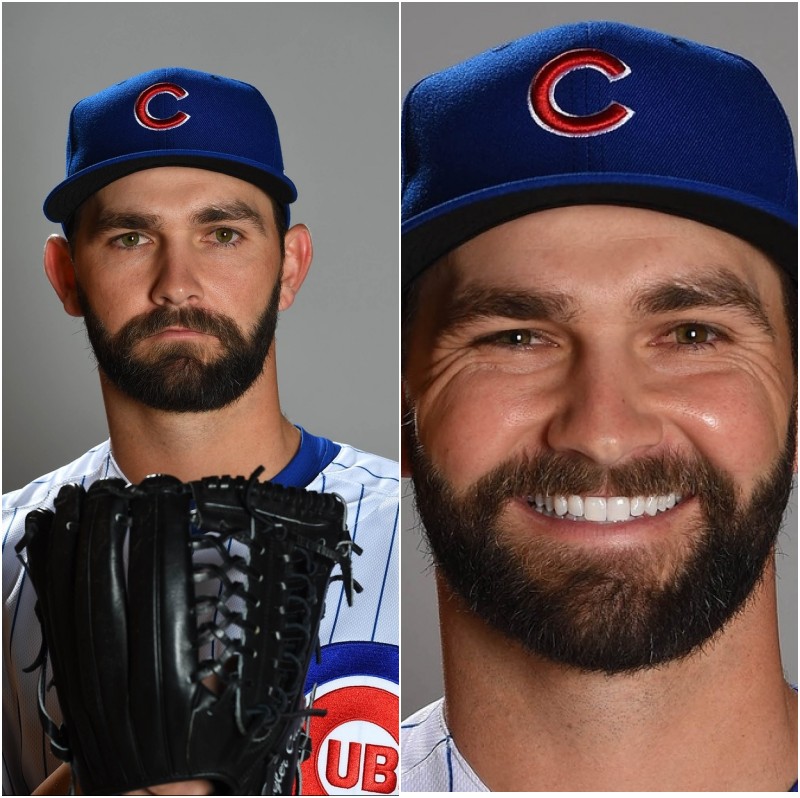

There was pressure. Smart baseball people were calling him a “legit breakout candidate” and a “steal” for the Cubs. Theo Epstein even called him “uber-talented” (something he hadn’t been called since his prospect days in Los Angeles). And of course, there were the Arrieta comparisons. He was not Arrieta, would never be Arrieta, and he had come to terms with this (though there was that awkward phase where he had grown out his beard, started consuming strictly kale juice and nuts, and tried with limited success to rally the team into doing Pilates before games).

Once he had settled in, Chicago was heaven, at least compared to the mile-high hellhole he had played half his games in since 2012. In Chicago, he could challenge hitters on the first pitch and get ahead in the count more often, no longer fearing that a light tap of his 96-mph (and rising) fastball would mean extra bases. In Chicago, he could maximize the spin on his curveball since, with the thicker air, it would actually curve. In Chicago, he could continue induce weak grounder after weak grounder, knowing the slick double-play duo of Addison Russell and Javier Baez would ensure a third straight season with a sub-.300 BABIP allowed.

It had been a season of light for Chatwood; everything was before him. He was not Jake Arrieta, but he was a valuable member of the best starting rotation in Major League Baseball. For him, and for Cubs fans, that was enough.

***

It is some evening in late October, and for Tyler Chatwood, it is the worst of times.

After being demoted to the pen mid-season and relied on sparingly, typically in low-leverage situations, he sits in the dugout—alone, despairing—watching the World Series go by while some other pitcher does what Chatwood could not do this season: throw the ball over the plate. Chatwood reflects.

How did he get here?

It started with the beard. Or rather, the beard (he suspected) was the basis for the (everyone knows now) lazy comparisons to the (he really doesn’t even like saying the name)… the other bearded, once-promising righty who, like Chatwood, was snatched up out of a bad situation by the Cubs. The former Cy Young winner who is now a Cy Young contender as a member of the Philadelphia Phillies. The Pilates guy.

He had done everything he could think of to make himself the anti-Arrieta: shaved his beard, started consuming strictly foods found in the $1 and $2 sections of the McDonald’s value menu, and gone on an anti-Pilates crusade, proclaiming it “fake DDP Yoga” during a pre-game interview with Kelly Crull.

Even so, the (in his opinion, really quite unfair) expectations remained. Chatwood had pitched as he had always pitched through the first few months of the season, and the breakout season that everyone pined for never materialized. As Chatwood’s strikeouts dwindled, so too did his innings per start, and Cubs brass’s confidence in their new toy. Jim Hickey had tried to maximize his curveball’s potential, Mike Borzello tinkered with his pitch mix and sequencing, Joe Maddon shifted starters to give him ample rest. None of these changes widened the single-digit gap between Chatwood’s walk and strikeout percentages, or kept the righty in long enough to face the skeletal Pittsburgh Pirates’s order a third time. By the All-Star break, Chatwood had been relegated to long relief while Mike Montgomery induced grounder after weak grounder.

As if it was his fault he couldn’t throw the ball over the plate and was on track for a third straight season of walking 10 percent of batters he’d faced. As if it was his fault that he didn’t possess a real putout pitch (not even the high-spin curve that everyone was gushing over when he signed). As if it was his fault that Theo had finagled a Cy Young winner for Scott Feldman a few years ago.

Despite the Cubs successes, it had been a season of darkness for Chatwood; nothing was before him but two more years of being a well-paid long reliever. For him, and for Cubs fans, that would never be enough.

Lead photos courtesy Jayne Kamin—USA Today Sports