We are into week four of the regular season and Javy Báez remains near the top of the major-league offensive leaderboards. The “unicorn,” as former BP Wrigleyville editor Rian Watt once called him, is turning people’s heads once again, not only for his defense—but of course, that too—but for the prodigious power, intelligent baserunning, and timely hitting that forced prospectniks to toss out lofty comparable players in their reports. Joe Maddon himself has compared the 25-year-old infielder to Manny Ramírez, should Báez fulfill his potential.

Báez has been in the majors since mid-2014, and while he’s dazzled in the field, until this spring he had been a merely average offensive player at his best. The question on everyone’s minds, then: What has Báez done differently this year, and can he continue to be this good?

Others have begun to dig into this question as well, but I think there are some wrinkles to Báez’s game that have been smoothed over by other writers. I do recommend Sheryl Ring’s fantastic piece about Báez, which examines some aspects of Báez’s approach that I will also cover.

To begin this investigation, though, I’ll offer some quantitative measurements of Báez’s greatness. Here are Báez’s rate stats for each year he’s been in the big leagues:

| BA | OBP | SLG | TAv | K% | BB% | |

| 2014 | .169 | .227 | .324 | .197 | 41.5 | 6.6 |

| 2015 | .289 | .325 | .408 | .268 | 30.0 | 5.0 |

| 2016 | .273 | .314 | .423 | .275 | 24.0 | 3.3 |

| 2017 | .273 | .317 | .480 | .274 | 28.3 | 5.9 |

| 2018 | .292 | .363 | .736 | .348 | 21.3 | 7.5 |

His improvement so far this season is obvious and impressive. The slugging percentage is what stands out, of course, as Báez has cruised toward seven homers, three triples, and two doubles; just as impressive, however, are Báez’s improved strikeout and walk rates. He’s not going to be Kris Bryant or Anthony Rizzo in terms of plate discipline—he won’t even be Willson Contreras in that department—but he has managed to bring his walk rate up close to league average, while cutting down significantly on the strikeouts that have previously plagued his offensive game.

This is where I say that Báez is going to regress. The chances of him slugging .736 for a full season are miniscule, and the chances of him posting a good-but-not-exceptional .363 OBP are relatively small. But, while many in the baseball analytics community might doubt Báez’s ascendance, I am a believer. It’s not unusual that a star prospect with Báez’s profile might struggle in his first few major-league seasons before making the necessary adjustments to bring out the remarkable skills that manifested as a minor leaguer. This is what sets Báez apart from his double play counterpart, Addison Russell: Báez’s best skills (power, defense) have been hampered by other aspects of his game that have needed work (contact, plate discipline); Russell’s best skills (hitting for average, defense) have been hampered by, well, not hitting for average or having any semblance of a useful approach at the plate. Báez has supplemented his power with improvements in his approach, accentuating that stand out skill.

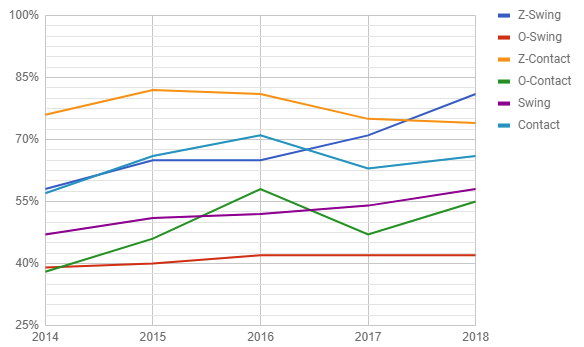

For evidence, I’ll turn to a few different sources of data. First, Báez’s pure plate discipline percentages. Here are Báez’s in-zone (Z-Swing) and out-of-zone (O-Swing) swing rates, his in-zone (Z-Contact) and out-of-zone (O-Contact) contact rates, and his overall swing and contact rates for each year of his career.

In the words of the immortal Buffalo Springfield, there’s something happening here. Except, with Báez, it’s quite clear: he’s swinging at a lot more pitches in the zone while keeping his out-of-zone swing rate about the same. This has produced some interesting secondary results, as he has made less contact than ever on pitches in the zone, while improving his out-of-zone contact and overall contact rates from 2017. Read in conjunction with his improved strikeout and walk rates, this might be cause for concern, as one might instinctively believe that Báez cannot keep swinging at so many pitches while striking out less.

In short, that might be true. However, Báez’s quality of contact, the type of pitches he’s seeing, and where he’s being pitched are all important factors to also consider, and factors that—I think—mitigate some of the concern that he might revert to 2016-2017 Báez.

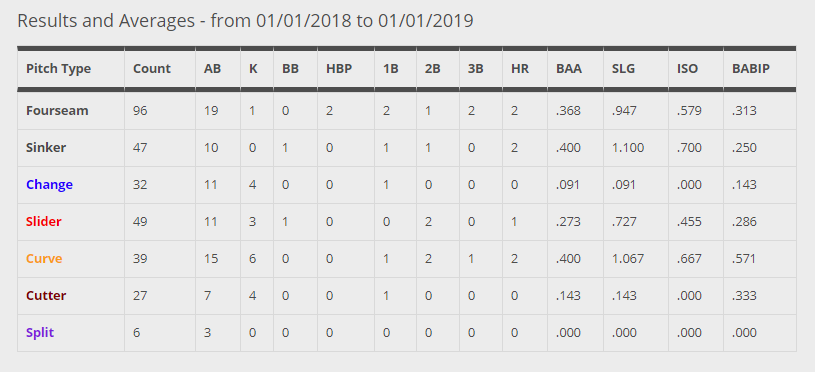

Báez is hitting the snot out of the ball. This much is certain. His hard- medium-, and soft-contact rates are good but not great, with exit velocity numbers to match (take these with a grain of salt, as always), but one gets the sense that Báez has found the sweet spot a lot more often this year than in years past. To picture that eye-test hunch in data form, let’s look at Báez’s results for different pitch types.

In a word, yowzers. Though from an admittedly small sampling, only changeups (primarily from lefties) and cutters have given Báez fits this year, as he’s crushed just about everything else. Against four-seam fastballs, sinkers, sliders, and curves, Báez is mashing. For context, Báez’s career batting average and slugging percentage versus curveballs are .168 and .283, respectively.

We need to slice this data one more time, though. Báez notoriously struggles with two strikes, and I’m not sure that 2018’s numbers do anything to disprove that notion. In fact, Báez has no hits versus two-strike sinkers, sliders, curves, or cutters this year. Pitchers can probably still get Báez to chase a breaking ball with two strikes, or stymie him with a well-placed fastball.

Báez, though, has succeeded much more early in the count; this makes sense considering his higher in-zone swing rate. Five of Báez’s seven home runs have come with no strikes: two on four-seamers, and one each on a sinker, slider, and curve. With one strike, Báez is still potent, as his other two homers came off a one-strike sinker and one-strike curve. Perhaps Báez (possibly with the aide of new hitting coach Chili Davis) has unlocked the key to his success by being more aggressive early in the count. Such an approach has clearly paid off for him, as he’s shot to the top of many offensive categories with nearly a month of this season in the books.

There’s one final aspect to Báez’s game that I feel the need to address, and that’s his astronomical home run-per-flyball percentage. Before Tuesday’s game, that number stood at a round 33.3 percent, or sixth-highest in the majors. However, Báez’s flyball rate, which sits at 39.6 percent, is nowhere near the most flyball-happy hitters in the league. In fact, he ranks all the way down at 63rd of 177 qualified hitters. He is hitting lots of line drives, boasting a 28.3 mark in that category, but Báez has, significantly, not hit more flyballs than usual. His career mark is at 37.4 percent. Báez has always been a flyball hitter because of his aggressive uppercut swing, but counting him as one of the players buying into the “flyball revolution” seems foolish, especially considering the fact that we can explain most of Báez’s early-season success in other ways. The home run-per-flyball rate will almost certainly come down, but Báez, as the 2015 BP Annual presciently suggested, “has an unconventional swing, though most suggest that improvements to his approach, not cleaner mechanics, are the key to future success.”

—

Báez’s success this year is the kind of success that fans hope for when they first hear about an exciting player making their way through their favorite team’s farm system. For those who always believed that Báez could be the 35-plus home run hitter that evaluators pegged him for early on, it’s downright cathartic. The infielder himself has endured personal tragedy and professional struggles, and while the 2016 World Series championship surely helped assuage the latter, one can sense that Báez wasn’t content being a great defensive player who sometimes put together enough of a hot streak to hit 25 homers.

In a great piece last spring, BP’s Jarrett Seidler wrote of Báez as one of those players who becomes great, but in a different way than we expected. Seidler compares Báez to Mookie Betts; actually, he suggests that their prospect profiles and their major-league outcomes have been all but reversed, with Báez becoming the glove-minded infielder and Betts becoming the world-class hitter.

Now, with Báez showing signs of developing an approach at the plate that fits his swing and style, one can see him approaching his potential—which Seidler, I think very appropriately, saw as “a lot more like Adrián Beltré than the name that always got mentioned with him as a prospect, Gary Sheffield.” Beltré managed a league-average .748 OPS over his first 3000 plate appearances, and several seasons similar to Báez’s 2016-2017, before breaking out in 2004 to the tune of 48 homers and a .334/.388/.629 line. That was Beltré’s age-25 season.

It’s 2018, Javier Báez is 25, and he sports a career .748 OPS.

Lead photo courtesy Matt Marton—USA Today Sports

Wow. The identical OPS numbers for Báez and Beltré after 3000 at bats is spooky. Hopefully Javy can have the same kind of break-out season at age 25.