Though the 1870 championship game involved a team called the Mutuals, the conclusion was anything but. In many ways, the game was about as improbable as one could be. The reigning champions entered the season expecting to easily trounce their way to another championship, while the newly formed Chicago White Stockings should have been happy with a participation trophy. The Mutuals won the most games against professional teams, while the White Stockings won the fewest. Both teams began the season as expected, with the Mutuals trouncing Chicago in the pair’s first three meetings. However, Chicago grew increasingly formidable, playing the team’s best baseball when it mattered most, sneaking into the championship game past Philadelphia and Cincinnati, to the latter’s horror and dismay. But by the end of things, nobody could deny Chicago’s role in creating a game for the ages.

The Creation of the Chicago White Stockings

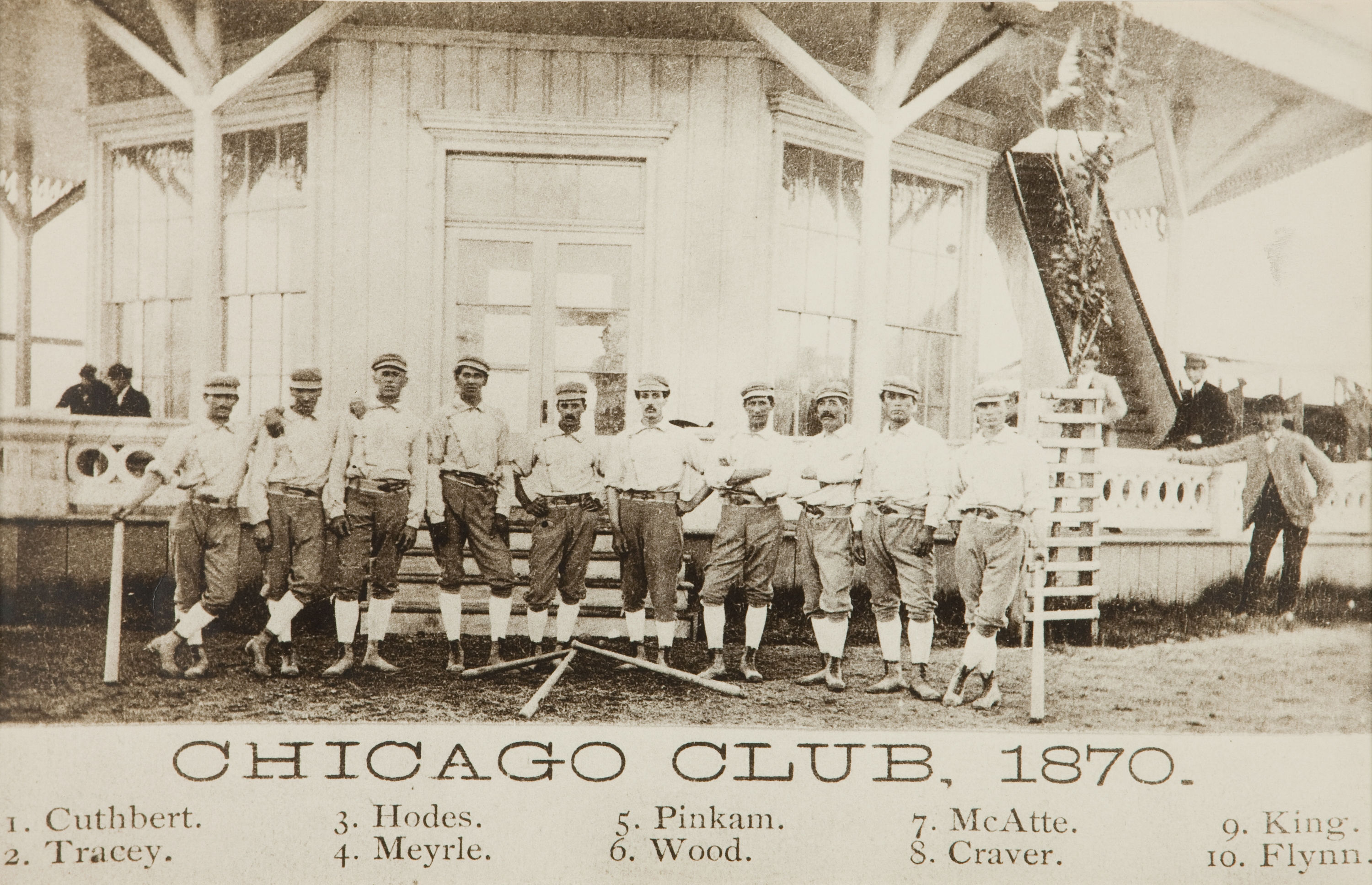

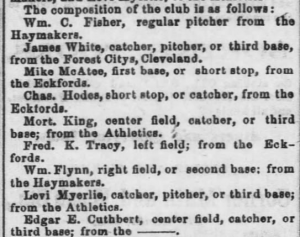

Inspired by the success of the country’s first professional baseball team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, and wanting to outdo its economic rival, Chicago created its first professional team in 1870, creatively named the White Stockings. Yet to be a thriving community of baseball players, the city found itself incapable of finding ten professional baseball players worthy of competing against Cincinnati, and in late January, it seemed like the team would never come into fruition. Then the shareholders brought in Tom Foley, the area’s best baseball player, to help craft the team. He made his way to New York, the epicenter of baseball, to personally pitch the team to the city’s finest players. Though the process was slow, it was eventually successful, and the team soon comprised nine excellent players, most notably team captain and manager, second baseman James Wood, who lured in the other players with salary advances he paid himself.1

Returning to Chicago with Foley and Wood were six of the nine other players: first baseman Mike McAfee, shortstop Charlie Hodes, center fielder Mort King, left fielder Fred Treacy, second baseman William Flynn, and right fielder Edgar Cuthbert. The men were immediately welcomed by the small but growing baseball community. They were applauded for being “well-behaved, strictly temperate, good-looking young men” who could rival Cincinnati.2

baseman Mike McAfee, shortstop Charlie Hodes, center fielder Mort King, left fielder Fred Treacy, second baseman William Flynn, and right fielder Edgar Cuthbert. The men were immediately welcomed by the small but growing baseball community. They were applauded for being “well-behaved, strictly temperate, good-looking young men” who could rival Cincinnati.2

Without much infrastructure available to support a professional organization, the team leased two fields from the city: Dexter Park, beside the South Side Union Stockades, and the North Side’s Ogden Park. Though neither field was equipped to handle the demands of a professional team, both—particularly Ogden Park—were in rapidly expanding areas of the city which attracted middle-class residents who were quickly growing to enjoy baseball. The end of the Civil War and the beginning of the Reconstruction Era invigorated Chicago’s economy, drawing in workers by the thousands to populate the new steel mills. Adding a professional baseball team to the city capitalized on this expansion and began the process of building a sense of camaraderie among the (white) working- and middle-class populations.

Finding Their Footing

Though the team swept through the South in a series of exhibition games in April and early May, frequently scoring over 100 runs per game, newspapers of the more established professional teams were reluctant to give them credit for their performances. The Philadelphia Evening Telegraph wrote of the team, “it is composed of the very best men, as it may well be, for it is a ten thousand dollar party. It is, however, nothing but a picked nine at best, not a club nine, as those of the Athletic, the Atlantic, and the Red Stockings are…. They may not be found so very strong when on the field and opposed to nines who have been playing together for a long time.”3 It was assumed by most that the White Stockings would finish well behind the Philadelphia Athletics, Brooklyn Atlantics, Cincinnati Red Stockings, and New York Mutuals.

In Chicago, though, the team was quickly declared an overwhelming success, “fully equal to any which the Red Stockings, Nationals, or any other club.” The team’s first game in the city, on May 21st versus the city’s amateur team, gathered a crowd of roughly 2,000 men and women, with half the spectators in in the stands at Ogden Park and the other half piled onto mounds of lumber outside the park’s fences. The Chicago Tribune declared the White Stockings’ fielding “perfect” and the hitting “immense,” as the team beat the Amateurs 49-4. Accompanying the detailed game recap was a glossary of baseball terms, designed to provide the reader and hopeful White Stockings fan with the ability to understand the “beautiful and noble game” with “tolerable success.”4

After drubbing teams in St. Louis and Milwaukee and garnering huge crowds in the process, the White Stockings turned their attention to the “premiere” teams, first beating the Athletics 39-5, with both Meyerle and Pinkham pitching exceptionally for the club. The team continued its success throughout the remainder of May and June, igniting quite the rivalries with Cleveland and Philadelphia, whose papers frequently sparred with the Tribune, the former refusing to acknowledge Chicago’s success and the latter declaring the Ohio fans “too thin-skinned.” Whereas Chicago “[was] not wrapped up in the successes and failures of the White Stockings” because it is a city of “ample resources,” declared one Tribune article, Cleveland and Cincinnati were not so fortunate economically, and were only notable due to their baseball teams.5

Though the White Stockings easily handled the teams from Ohio, the East Coast was a different story. The Atlantics and the Mutuals handed the team back-to-back losses in early July, losing 90-20 to the Atlantics and 13-4 to the Mutuals. The team then lost 17-12 to the Athletics, prompting newspapers of all cities to declare the White Stockings inferior to the older, more established trio of teams. This string of tough defeats prompted the team to switch baseballs, from the “lively” ball used by the Mutuals and Atlantics to the “Ryan” ball favored by the Red Stockings. This change combined with the return from injury of Meyerle, King, and Craver, it was thought, would return the team to its earlier glory.6

The Mutuals journeyed to Chicago for the first time that season on July 24th, offering the White Stockings its first chance at redemption. The game drew 6,000 fans, the team’s largest crowd thus far in the season. Unfortunately, the fielding and hitting that was earlier heralded as perfect was nowhere to be found. The Mutuals, again, emerged victorious, blanking Chicago 9-0.7 The following week, Chicago lost to the Boston Harvards and again to the Athletics. King, Hodes, Flynn, and Craver were all injured. The city’s two primary newspapers, the Tribune and the Republican, lambasted the players for earning an excessive amount of money to underperform and encouraged the team to “sell” in preparation for the following season.8

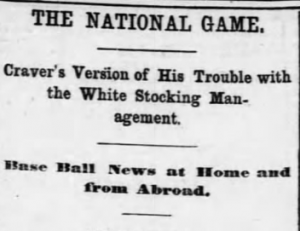

In response to the poor play, the team’s stockholders removed the oft-injured Craver from the team,  beginning a feud between the player and the club that would last weeks. The team released a letter to the Tribune, stating Craver had violated a number of team rules, including, drinking, smoking, and betting on games, prompting the team to end his contract, effective immediately. The following day, Cramer responded to the letter, calling it a “tissue of falsehoods and glittering generalities” and calling its basis a “grand crater of jealousies and rivalries” that will continue indefinitely. Of course, he did admit to gambling on several occasions, noting that if he is guilty, so is the entire team.9

beginning a feud between the player and the club that would last weeks. The team released a letter to the Tribune, stating Craver had violated a number of team rules, including, drinking, smoking, and betting on games, prompting the team to end his contract, effective immediately. The following day, Cramer responded to the letter, calling it a “tissue of falsehoods and glittering generalities” and calling its basis a “grand crater of jealousies and rivalries” that will continue indefinitely. Of course, he did admit to gambling on several occasions, noting that if he is guilty, so is the entire team.9

The removal of Craver from the team, regardless of its suspicious details, did wonders for the White Stockings, who began playing better than they had all season. Facing off twice against the Atlantic, the best team in the league who had shut out both the Athletics and Red Stockings, at the end of the month, Chicago emerged victorious. The team won the first game 12-4 and the second 7-1, setting up a month of baseball that would catapult them to the top of the standings. By the end of September, they had defeated every other professional team, including the Red Stockings, making them beloved in the city. “The Chicago troops who fought at Donelson and Shiloh, and who marched triumphantly into Vicksburg, were not received at home with more honors or greater applause than these nine ballplayers,” remarked one newspaper of the crowd waiting for the team on its return from Cincinnati.10 There was now no newspaper which could deny Chicago’s legitimacy.

The Championship Game

Near the close of the season, Cincinnati and Philadelphia had faltered slightly, leaving Chicago and New York as the best two teams in the country. By the middle of October, Chicago had played 69 games, winning 61 while scoring 2,289 runs and allowing only 696, while the Mutuals had lost only five games.11 Though there was no official league, a championship game was played between the top two teams in the country, as agreed upon by the teams’ owners.

The game, between the White Stockings and Mutuals, began this championship series in Chicago on November 1st. The Mutuals had beaten Chicago in three of the four games the teams had played that season, and the defending champions were expected to easily beat Chicago, particularly since they had trounced the Red Stockings earlier in the week, while Chicago had not played high-caliber teams in several weeks.

Though the day began ominously for the White Stockings as Fred Treacy’s custom baseball shoes were stolen from his locker prior to the game, they jumped out to a 3-0 lead after the first inning in front of 6,000 fans. They added two more runs, making it 7-5 after seven innings. Then Pinkham ran into trouble, allowing the Mutuals to score eight runs in the ninth inning to take the lead for the first time in the game, and it seemed like Chicago had finally reached the disappointing end of its improbable run. But no events of the previous eight and a half innings prepared the teams or fans for what was to come.

The White Stockings scored five runs with one out in the inning, making it 13-12 Mutuals, requiring only one more run to tie and two to win. Like any good pitcher, the Mutuals’ Rynie Wolters, rather than blaming himself for the inning, lashed out at the umpire. After throwing 12 consecutive balls to load the bases, Wolters declared the umpire crooked, throwing down his glove and walking off the mound in protest. Over the next half hour, each Mutuals player begged Wolters to return to the mound, but he was steadfast in his decision. Even if he had agreed to return to the mound, the entire field was overflowing with fans who rushed it to congratulate the Chicago players as soon as it appeared the Mutuals had forfeited. However, the team did not officially forfeit. Rather, before the police could clear the field of the fans, it became too dark to continue the game. Because the ninth inning had never been completed, the umpire ruled the Mutuals’ comeback did not count, officially declaring the White Stockings the victors, with a 7-5 score after eight innings.12

Enraged by the outcome, the Mutuals petitioned the Chicago team to hold a rematch on neutral ground with a mutually selected umpire. They declared the White Stockings owed it to them both due to the corrupt nature of the umpire and the fact that of the four major teams, the White Stockings had the fewest “professional” wins and therefore should not have been in the championship game in the first place. Confident in their ability to beat the Mutuals and assured by local fans that the game would not impact their status as champions, the White Stockings agreed to a rematch to make place on November 4th in Cincinnati.13

had the fewest “professional” wins and therefore should not have been in the championship game in the first place. Confident in their ability to beat the Mutuals and assured by local fans that the game would not impact their status as champions, the White Stockings agreed to a rematch to make place on November 4th in Cincinnati.13

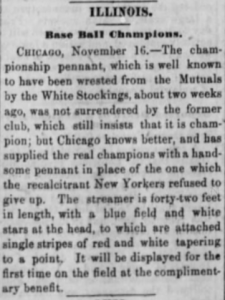

Despite the parameters of the game being fully mutually agreed upon, it never happened. The White Stockings alleged that on the morning of the game, they received a telegram from the Cincinnati hotel in which the Mutuals were staying, stating the Mutuals had left for New York that morning and the game had to be canceled.14 Conversely, New York blamed the cancelation on the White Stockings, claiming that owner Tom Foley had withdrawn from the agreement.15 Chicago, thus, happily retained its title of baseball champions, but its validity would continue to be questioned.

The controversial events of this championship game prompted the professional teams’ owners to establish a more uniform, regulated organization. In the winter months, they gathered together to create the National Association of Base Ball Players, the first official professional baseball league. Though this league had its own share of difficulties, and lasted only four years with tepid support from its member teams, there was never again such a contested championship.

NOTES

1 https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/baseball-of-the-bygone-days-by-jimmy-wood-part-4-e9eee71bd35e

2 Leavenworth Times, March 15, 1870, pg. 4.

3 Philadelphia Evening Telegraph, April 11, 1870, pg. 8.

4 Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1870, pg. 3.

5 Chicago Tribune, June 6, 1870, pg. 4.

6 Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1870, pg. 4.

7 Chicago Tribune, July 25, 1870, pg. 4.

8 The Buffalo Commercial, August 1st, 1870, pg 1.

9 Chicago Tribune, August 22nd, 1870, pg. 4.

10 Titusville Herald, September 23rd, 1870, pg. 2.

11 Kansas State Record, October 21, 1870, pg. 1.

12 Chicago Tribune, November 2nd, 1870, pg. 4.

13 Chicago Tribune, November 3rd, 1870, pg. 4.

14 Chicago Tribune, November 4th, 1870, pg. 4.

15 Titusville Herald, November 5, 1870, pg. 2.