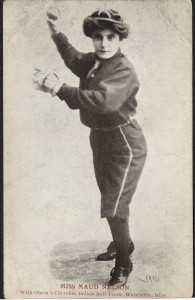

The $10,000 custom Pullman coach parked outside a makeshift canvas grandstand was one of the most exciting sights in small-town America in the summers of 1902 and 1903. For inside the canvas walls was a spectacle irresistible even to the most proper of gentlemen: the Chicago Stars, and in particular, Maud Nelson. The Chicago Stars was the premier women’s professional baseball team in the country, and Maud Nelson was a pitcher so good only her gender held her back. Throughout these two summers, this pairing of the Stars and Nelson created the blueprint for many women’s teams to come.

Laying the Groundwork

Women’s professional baseball in Chicago began in the late 1880s, when Sylvester Wilson created the first Chicago Bloomer Girls team, which went by a plethora of names, most frequently the Chicago Black Stockings. This team lasted only one season before disbanding, but various other men latched onto the idea, creating in turn their own women’s teams in Chicago through the 1890s. These teams were all of the barnstorming variety, playing against amateur male teams throughout the midwest, with none lasting longer than two years.

During this period, baseball became increasingly acceptable for girls and women to play. It was still frowned upon by the majority of society, of course, but many high schools in the area instituted baseball as a common gym class activity, believing it would not only make women healthier, but it would instill in them the same values as it would in men, namely teamwork and deference to authority. Nonetheless, the concept of women undertaking baseball as more than a hobby was preposterous.

As such, women’s teams, as was and would be the case for Black teams, were forced to embrace the spectacle of it all. They frequently incorporated circus-like elements into games, hiring pre-and-post-game performers, and played up their femininity during games. Teams shared anywhere between 20 and 50 percent of ticket revenue, and the more outlandish the teams were, the more money they took in. But crowd size still varied widely by city. In August of 1900, the Chicago team pla yed three games in one week in Ohio, drawing crowds of 1,200, 500, and 3,000. The 3,000 spectators signified the potential of the team, but crowds of 1,200 and 500 were more often the reality. This dearth of revenue forced a high turnover rate, as players could not make enough to justify abandoning the responsibility of everyday life each summer. They had husbands to tend to and children to have, and baseball was plucked from the sad reality of their lives.

yed three games in one week in Ohio, drawing crowds of 1,200, 500, and 3,000. The 3,000 spectators signified the potential of the team, but crowds of 1,200 and 500 were more often the reality. This dearth of revenue forced a high turnover rate, as players could not make enough to justify abandoning the responsibility of everyday life each summer. They had husbands to tend to and children to have, and baseball was plucked from the sad reality of their lives.

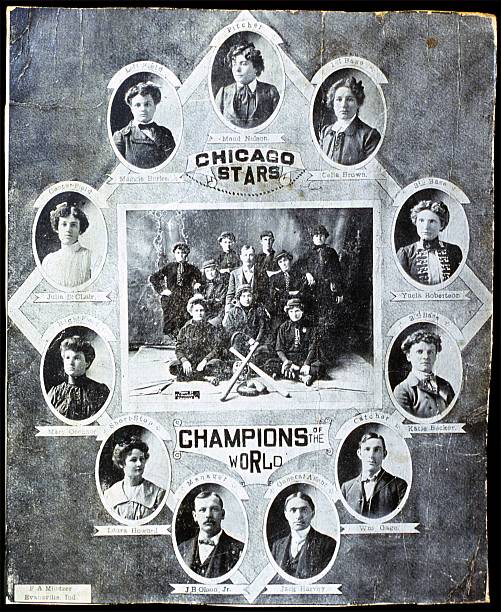

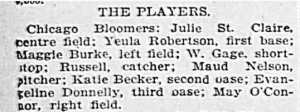

Things slowly began to change, though, when, in the fall of 1901, J.R. Olson Jr. (who would become Maud Nelson’s husband) took control of the team. He sought to capitalize on the unique talent and star power of Nelson, who was entering her second year with the team. He changed the name to the Stars and quickly mapped out a cross-country tour, beginning in Tampa and working its way t o Vancouver before returning to the Midwest to finish the year. Unlike in previous seasons when the roster was for large stretches composed entirely of women, Olson succumbed to the norm, adding three men—two pitchers and one catcher—in order to make the Stars more competitive.

o Vancouver before returning to the Midwest to finish the year. Unlike in previous seasons when the roster was for large stretches composed entirely of women, Olson succumbed to the norm, adding three men—two pitchers and one catcher—in order to make the Stars more competitive.

Integral to Olson’s plan, and the success of the Stars, was to maintain the level of spectacle while insisting on the capabilities of his players. Early in 1902, Olson released a statement to the press, which read: “the management wishes it understood that the Bloomer Girls do not travel with the intention of drawing crowds, just through the novelty of ladies playing ball, but through their ability to play an interesting and scientific game of ball.”1 The Stars were a must-see because they were women and because they could play baseball.

Though Boston’s Bloomer team had in recent years assumed the title of “champions of the country,” by mid-May of 1902, the title had switched to Chicago. Every town and city for the remainder of the season advertised the Stars as the championship team, sure to give the local boys a run for their money. In the quieter towns, like Princeton, Indiana, the arrival of the Stars was still seen as “the only novelty of the season,” but the balance Olson wanted appeared to have been struck.2 In several short months the Stars had gone from a short-lived novelty act to a potentially successful women’s team.

On The Field and In the Newspaper

Drawing on Chicago’s vast population of immigrants, these early teams were predominately comprised of Western European women, like Maude Nelson, whose birth name was Clementina Brida. This mix of women was eclectic enough to be interesting while upholding the racism that prevented women of color from joining such a team. They could go anywhere and be unique without being off-putting for their white spectators. Combined with this balance of intrigue and talent, the team quickly rose to success in the spring of 1902 and maintained that success for the following two years. Accompanying this success, however, was a concerted effort on behalf of the male baseball community to make sense of the team and women’s support of it.

In the past, every single game determined the women’s viability as legitimate baseball players. When the team lost, it was declared that women had no future in the sport; when the team won, they were good enough to rival any male amateur team. But this team of women, due to Nelson and a few others, were generally viewed as semi-competent players even in losses. Throughout 1902 and 1903, a variety of newspapers called the team “first class” “wonders at the game”3 in all respects and a perfect “exhibition to how girls can be taught to play baseball.”4 They won the first couple of games of 1902 before losing a string of tough matches to several South Carolina teams, but the losses did little to dampen the excitement of the team. Instead, sportswriters were able to soothe their male egos with each of the Stars’ losses while praising the team for a good effort. Comments like “they were very clever players, and the local team had all it wanted to do to m ake the score in its favor,”5 and “the girls made their opponents work hard to win”6 more often than not were followed by lengthy descriptions of the Stars’ losses, while typically short paragraphs accompanied victories.

ake the score in its favor,”5 and “the girls made their opponents work hard to win”6 more often than not were followed by lengthy descriptions of the Stars’ losses, while typically short paragraphs accompanied victories.

Not only were the women advertised largely as competent players, but their games, in contrast to men’s, were affairs to which one could take one’s whole family without fear of seeing anything inappropriate. While the effort to clean up men’s professional baseball would not exist for another several years, rural towns which featured the most “rough and tumble” men’s teams were overjoyed by the opportunity to witness “classy” baseball while using the Stars to shame their men’s teams into reform. The women were just good enough for the men to become jealous of the crowds of spectators at each Stars game and the “meritorious” play of the women.7

Their talent was often compared to women’s teams of previous years as well as women’s expected roles in society. One Greenville newspaper wrote in 1903: “They call themselves the “Chicago Stars” and they are really stars…several years ago a female crowd of bum ballplayers…attracted a good crowd, but the article of baseball they put up was decided so poor that even the “free pass” crowd sneered at them.”8 The extent of the players’ talent frequently surprised writers, spectators, and opposing teams who thought the local team would win each game handedly. Of course, these praises were often handed out for displays of the bare minimum of skill, from being able to hit the ball out of the park to making strong throws to first.

Maud Nelson, right fielder Julia St. Clair, and left fielder Maggie Burke received the bulk of the genuine praise for their talent. Nelson, considered the best women’s pitcher to ever exist, was detailed as being able to “regulate the speed of her delivery and deal out curves which puzzle the best of hitters.” She had “mastered all the professional twirlers, and pitches with ease and grace.”9 St Clair “skillfully demonstrated her ability to swat the leather good and hard when she went to bat,” and proved a competent fielder.10 Meanwhile, Maggie Burke was capable of routinely making “fine catches” and “hitting well with the stick.”11 Each of these three women, it was determined, would impress under any situation, and their presence on the Stars legitimized the rest of the roster.

1903 and the Future

As the Chicago Stars toured the country in 1902 and 1903, they brought out the best and the worst of American society. Their detractors frequently argued about the players’ gender, calling the women “manly” and “unnatural” while asserting the spectacle would “ruin society” and corrupt their own women relatives. They were barred from playing in various cities by mayors who agreed with the misogynistic sentiments of many men across the country. Most newspapers, particularly those in Chicago, paid them no attention. But far more cities and towns welcomed them, and the white women who flocked to these games walked away inspired to start their own teams.12

The Chicago Stars lost Maud Nelson and J.B. Olson at the end of the 1903 season, and featured a 100% roster turnover. Nonetheless, the various iterations of the team found success traversing the country for the remainder of the decade, inspiring many more white women’s teams to do the same. Though it would be another 30 years before a true professional women’s league was created, the Chicago Stars of 1902 and 1903 laid the groundwork.

Notes:

1 Jean Hastings Ardell, “Breaking into Baseball : Women and the National Pastime,” (Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), 144.

2 Princeton Daily Clarion, March 29, 1902, pg. 5.

3 Roanoke News, August 21, 1902, pg. 3.

4 New Berne Weekly Journal, August 29, 1902, pg. 4.

5 Wilmington Morning Star, May 3, 1903, pg. 1.

6 Washington Times, August 14, 1902, pg. 3.

7 Goldsboro Daily Argus, August 23, 1902, pg. 4.

8 Greenville News, April 10, 1903, pg. 4.

9 Washington Times, August 14, 1902, pg. 3.

10 Richmond Times, August 21, 1902, pg. 2.

11 Washington Times, August 14, 1902, pg. 3.

12 Scranton Republican, June 9, 1902, pg. 8.