“After 12 years in the major leagues, I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes”

- Curt Flood

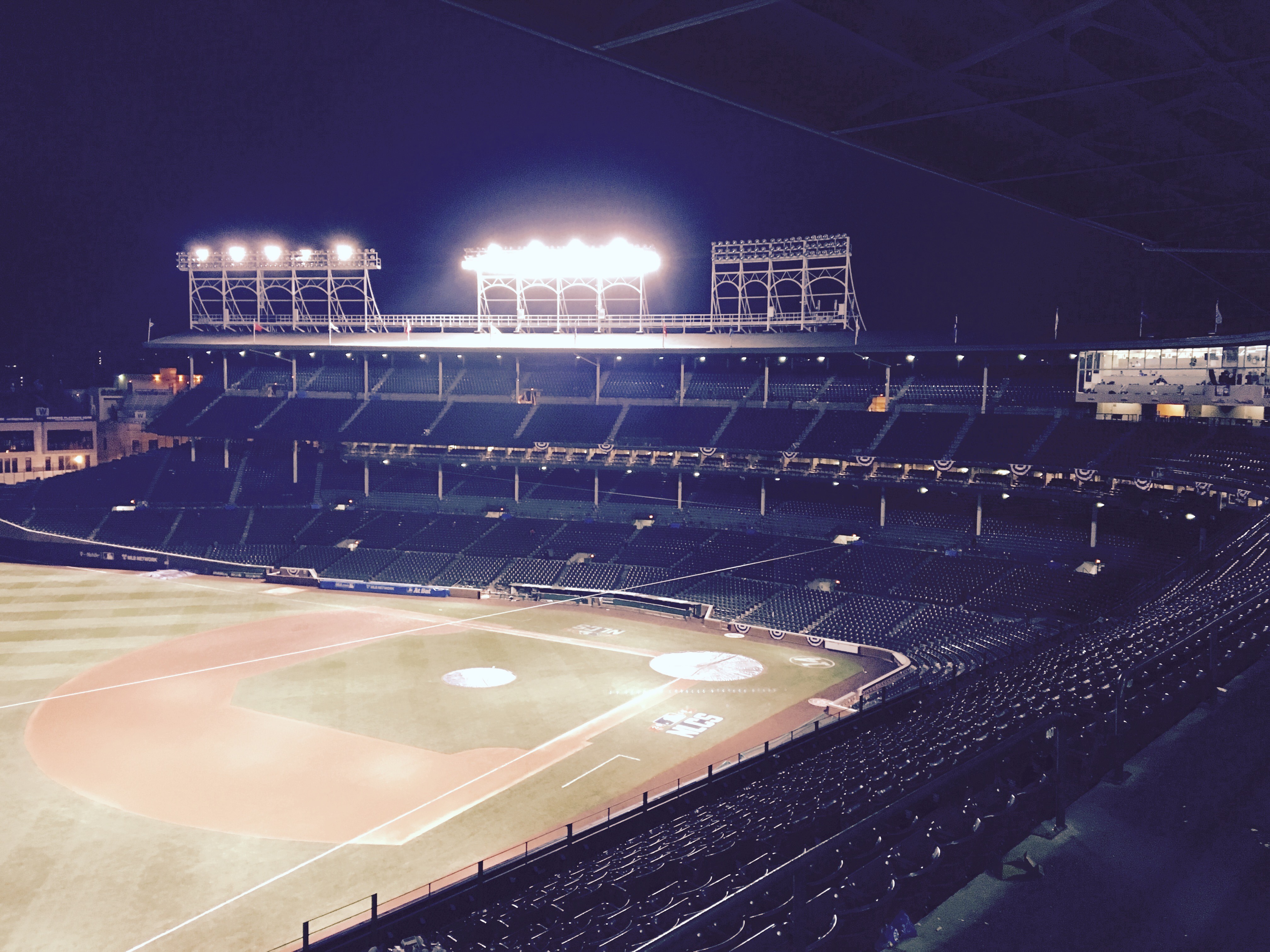

Arthur Goldberg was born in Chicago to immigrant Jewish parents from Ukraine. Although his father was highly educated, he could only find work as a peddler, forcing his children to also find work. Arthur undertook various jobs, but as a young Cubs fan, his favorite one was selling coffee at Wrigley Field during the prohibition. He did not last long at the job, however, because he was a gifted child who became the first, and only, Goldberg sibling to graduate high school—at the age of 16—and attend college, where he also excelled. After college, he went to Northwestern Law School where he received the highest scores to that point in the school’s history. His first legal victory came at 21, when he successfully argued his right to practice against the bar, who claimed 21 was too young to be a lawyer. He was appointed to the Supreme Court in 1962 by John F. Kennedy but left three years later to become US ambassador to the United Nations in hopes of bringing the Vietnam War to a resolution. However, after finding it difficult to work with Lyndon B. Johnson, he resigned in 1968 and unsuccessfully ran for governor of New York in 1970. Throughout all of this, he held a deep commitment to civil rights, leaving his first law firm in 1933 when asked to foreclose mortgages and focusing on the rights of steelworkers post-WWII.1

Goldberg spent his three years on the Supreme Court arguing for privacy and civil rights. He sided with the majority in Griswold v Connecticut (1965), the case in which the Supreme Court held that the Constitution protects the right of married couples to use birth control. In his concurring opinion, Goldberg cites both the ninth and fourteenth amendments to determine that “fundamental personal rights should not be denied such protection or disparaged in any other way simply because they are not specifically listed” in the Constitution.2 He also was staunchly anti-death penalty, and his dissent on the court’s denial to hear Rudolph v Alabama gave lawyers the chance to challenge en masse the constitutionality of capital punishment, leading to the suspension of the death penalty through the 1960s and 1970s. Based on his conception of personal liberty and its supremacy over states’ rights, he required state and local legislatures to protect the civil rights of black people, observe the separation of church and state, and uphold the rights of protesters.3

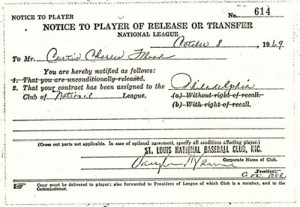

On October 7th, 1969, as part of a multi-player trade, the Cardinals sent Curt Flood to the Phillies. Angry about the trade, Flood refused to report to the Phillies, instead seeking legal action against the reserve clause that gave teams full ownership of their players, limiting free agency to those desperate enough to ask for an unconditional release. Concerning the practice, Flood wrote a letter to MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn:

After twelve years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.

It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decision. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.4

Kuhn denied this request, citing the reserve clause, prompting Flood to file a $1 million lawsuit against Major League Baseball on the basis of being treated like a slave. With Jackie Robinson, Hank Greenberg, and Bill Veeck Jr. agreeing to testify for Flood, all that was missing was the perfect lawyer.

Goldberg’s extensive human rights record and love for baseball made him the perfect candidate for the job. Goldberg crafted his argument to attack the reserve clause and antitrust laws on the basis of MLB being an interstate activity and therefore falling under federal regulations via the commerce clause. It was common practice for teams and owners to hide their revenues in order to decrease player salaries. He further attacked the 1953 Toolson v. New York Yankees decision that upheld MLB’s antitrust exemption due to interstate travel being “incidental” to the league and not generating revenue of its own. Goldberg recycled some of Toolson’s arguments, stating that the MLB did gain revenue from interstate travel due to fans traveling between states for games and digesting games in different states via radio and television. He further argued that the recent relocation of the Senators to Texas and the Angels to Anaheim suggested that owners implicitly believe fans capable of withstanding the potential hardships associated with players leaving via free agency; the relocation of a stadium is a far greater deal than the relocation of a player.5

In these arguments, Goldberg stated, “The court has passed on the reserve clause, I think, wrongly in two cases. It violates the US antitrust laws. It violates antitrust and common law of the states. It violates the 13th Amendment.” He further implored the Court to reverse these decisions because the reserve clause “extends beyond the continental United States. It extends to the minor leagues. It extends to the Mexican League. And it even extends to Japan.” Thus, baseball’s reserve clause violated antitrust laws because its impact was not simply intrastate.6

These seemingly well-thought-out arguments did little to mask Goldberg’s unpreparedness, though, as it seeped into his interaction with the justices and throughout his other arguments. He spent a great deal of time espousing the greatness of Flood’s career, going so far as to list off Flood’s yearly batting averages, concluding, “I am not a great mathematician, Mr. Chief Justice and associate justices, but this seems to me to be a batting average around 300.” He also twice noted that Flood won “several golden gloves competition, which is the competition for excellent fielding” and “was an artist who had an artist studio,” both of which were highly relevant to the case.7 Similar digressions and anecdotes permeated his statements and were accompanied by sentence fragments and rhetorical questions. On several occasions the Justices implored him to get to the brunt of an argument that barely existed, and when he finally reached his conclusion, he implied that the Justices’ recent arguments concerning antitrust laws did not “have any basis” on the current case.

The court, in defiance of Goldberg’s strong arguments and humble deference, ruled 5-3 in favor of stare decisis, or precedent. While Justice Blackmun, in the Court’s opinion, noted the MLB’s antitrust exemption was an “aberration,” the majority believed it an issue best suited for Congress, not the Supreme Court. That Congress has repeatedly failed to rectify this error was not the Court’s problem and was but a reflection of the popular opinion at the time. Blackmun further approved of the idea of consistency, both in following precedent and in MLB retaining the reserve clause, even when there exist underlying inconsistencies. Essentially, the Justices agreed Flood should be a free agent, but believed antitrust laws were the jurisdiction of Congress.

Later reflecting on his performance, Goldberg admitted he was unprepared and had primarily relied on his friendship with Justices Brennan and Douglas and his belief they would see the error of earlier cases and be as wary of precedent as he was. Part of this belief was well founded in that many assumed the Supreme Court under Burger would offer more conservative rulings and disregard much of the precedents established under the liberal Warren court, but as Goldberg, and America, realized, this was not the case.

Indeed, Goldberg declared he was caught off guard by the intensity of the questions, and admitted, “if I had understood the nature of the challenge, I would have prepared better.”8 Despite failing to capture a majority, though, his tactics may not have been entirely useless, as they partially worked on—or at least fell into place with—Justice Douglas, who wrote in his dissent that he regretted his Toolson vote, called players ‘victims’ of the reserve clause, and stated, “The unbroken silence of Congress should not prevent us from correcting our own mistakes,” all of which Marshall agreed with in his dissent.

Following this shocking defeat, Goldberg resumed practicing law in Washington DC and served as United States Ambassador to the Belgrade Conference on Human Rights in 1977. For his service toward civil rights, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1978.

Curt Flood, on the other hand, did not play professional baseball again, although he served as an announcer for the Athletics for a short period of time. In the months following the decision, he received hundreds of death threats from fans accusing him of destroying baseball. Meanwhile, Flood’s case opened the door to further and alternative challenges to the reserve clause, and within years of the case, players won free agency rights and calmer fans grew to appreciate the exciting nature of free agency.9

Further, in 1998, Congress passed the Curt Flood Act, which declared that Major League Baseball players were, indeed, covered under antitrust laws. In his statement on the act, President Clinton wrote: “It is sound policy to treat the employment matters of Major League Baseball players under the antitrust laws in the same way such matters are treated for athletes in other professional sports.” The threat of players filing an antitrust suit has moderated club owners and eased the tense relationship between them and the MLBPA. Although he did not realize it at the time, Curt Flood helped the MLBPA become the strongest players’ association in American sports.10

Although Goldberg did not lose his career as Flood did, his performance has gone down as one of the worst and most bizarre in Supreme Court history. As one audience member put it, it was “one of the worst arguments I’d ever heard – by one of the smartest men I’ve ever known.” But, like Flood, Goldberg did receive something in the way of redemption. In 2013, Justice Sotomayor presided over a re-enactment of the case, and the role of Goldberg was argued so convincingly, she declared it an obvious victory for Flood, and for Goldberg.11

1 David Stebenne, “Arthur J Goldberg: New Deal Liberal.”

2 Griswold v. Connecticut 381 US 479 (1965).

3 Stebenne.

4 William C. Rhoden, New York Times, June 20th, 1972.

5 Krister Swanson, Baseball’s Power Shift.

6 Flood v. Kuhn 407 US 258 (1972).

7 Ibid.

8 http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/13/sports/baseball/the-curious-case-of-curt-flood-revisits-a-suit-against-baseball.html

9 Swanson.

10 Nathaniel Grow,”Reevaluating the Curt Flood Act of 1998,” in Nebraska Law Review 87.3, 2008.

11 http://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/justice_sotomayor_presides_over_re-enactment_of_historic_baseball_case/