As we get closer to the start of the baseball season, I’ve found myself wondering why I am hopeful, and yet I worry about, the 2017 Cubs season.

I am old enough to remember most Cubs seasons of the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Each preseason, I felt the excitement of the unknown, like a blackjack player before the cards are dealt: this season would be, finally, “Next Year.” We all know how those seasons played out, but every spring I was excited for the upcoming season.

Baseball fans have chugged the optimism of a new season for more than a century, with plenty of reasons to imbibe: young players improve, new players join the team, injuries heal, the team finally hired a new manager, something unexpected and unpredictable may happen. The excitement of the unknown, mixed with justifiable hope.

Hope Survives, but Projections Erode It

Baseball depends on its fans’ undying hope, as Bud Selig told the Chicago Tribune all the way back in 2000 when asked about the threat of competitive imbalance:

“[O]ne thing I’ve known, I’ve been convinced of, is that every fan has to have hope and faith. If you remove hope and faith from the mind of a fan, you destroy the fabric of the sport. It’s my job to restore it.”

Over the years, Selig pushed MLB to make numerous rule changes to maintain fans’ hope by expanding the number of teams in the postseason. Until 1993, just four teams, the division winners in the National League and American League, advanced to the playoffs. After the 1994-1995 strike, MLB divided the leagues into three divisions each and added a wild card team, doubling the number of teams in the playoffs. With the introduction of the second wild card in 2012, more teams make the playoffs, and many more teams remain in the playoff hunt until later in the season, per the Hope and Faith Index, the brainchild of Gerald Schifman.

And yet, notwithstanding all of these changes, justifying hope should be a lot harder for most teams. Preseason projections are simply too good. PECOTA and other preseason projections tapped the first cracks in the reservoir of hope over a decade ago. Since then, PECOTA and other projection systems have improved, chiseling away fans’ rationale for hope, approaching the theoretical statistical limit for projection accuracy of 6.4 wins given the role that random luck or lack thereof plays over the course of a season. The result? Unless most fans willingly suspend disbelief with otherworldly strength and conviction, they know within a fairly narrow margin what to expect from their team.

Cub fans, happily, have many reasons for hope on the eve of the 2017 season. The 2016 World Series champs return the entirety of their young core, a healed Kyle Schwarber, four of five starting pitchers, and a strong bullpen anchored by a new closer. PECOTA agrees, as the Cubs are projected to win 91 games atop the NL Central, as analyzed by my BP Wrigleyville colleague Zach Moser. Fangraphs is even more optimistic, projecting the Cubs to win 94 games.

But Projections Aren’t Infallible: Meet the Flops

Returning to our blackjack analogy, the Cubs 2017 season looks like two face cards with the dealer showing an 8.

Having experienced the burn of the Majestic Star blackjack tables, I know not to count that hand as a win. And as an emotionally warped Cubs fan, I’ve found myself looking for reasons to worry about this Cubs season. What historical precedents exist for a team projected to succeed that ultimately faltered?

For that answer, I looked for teams that PECOTA expected to be good based on their preseason/offseason moves, yet faltered. I also added the requirement that the team had been good in the preceding season. These requirements should identify teams similar to the 2017 Cubs, while eliminating teams that (a) played well one season, and stripped the team down for a rebuilding project in the intervening offseason (see 2004 Florida Marlins), or (b) outpaced their projections due to a somewhat unexpected circumstances, like a sudden and highly successful influx of young talent (see 2015 Cubs).

Let’s call these teams the “Flops.” And to put a finer point on it, the Flops must meet three criteria:

- They had a winning % over .550 in the preceding season

- PECOTA projected them to win at least 89 games the following season

- They missed their PECOTA-projected win total by at least eight games

Here’s the complete list of Flops, along with some pertinent statistics:

| Team | Flop Year | Proj. Wins | Actual Wins | 1st Order Wins | Proj. Runs Scored | Proj. Runs Allowed | Actual Runs Scored | Actual Runs Allowed |

| Philadelphia | 2012 | 89 | 81 | 81.4 | 687 | 612 | 684 | 680 |

| Boston | 2012 | 90 | 69 | 73.8 | 845 | 751 | 734 | 806 |

| Tampa Bay | 2014 | 90 | 77 | 79.5 | 729 | 641 | 612 | 625 |

| Washington | 2015 | 92 | 83 | 88.5 | 671 | 579 | 703 | 605 |

Why did the Flops flop?

Having identified the Flops, I looked for common threads to answer the following questions: What happened? And how can the Flops tell us what to worry about for the 2017 Cubs repeat campaign?

What jumps out at me is that three of the four Flops allowed significantly more runs than their preseason projections (Philadelphia, Boston, and Washington), while their offensive output was all over the map compared to their projections. The uptick in runs must result from some combination of bad pitching, bad defense, and bad luck. Let’s look for the primary culprit.

Bad Pitching

All of these teams dealt with multiple injuries or trades that eroded their starting rotations, forcing at least two of their starters out of the rotation for a meaningful amount of time. If healthy, starting pitchers throwing every fifth day should get around 32-33 starts over the course of a 162 game season, and throw between 160-200 innings. All of the Flops had at least two starting pitchers that fell short of those numbers:

| Team | Pitcher | Starts Made | Innings Pitched |

| Philadelphia | Roy Halladay | 25 | 156.1 |

| Philadelphia | Joe Blanton | 20 | 133.1 |

| Boston | Aaron Cook | 18 | 94.0 |

| Boston | Josh Beckett | 21 | 127.1 |

| Boston | Daisuke Matsuzaka | 11 | 45.2 |

| Washington | Doug Fister | 15 | 103.0 |

| Washington | Stephen Strasburg | 23 | 127.1 |

The result of these pitching injuries is replacement level starters throwing more innings and giving up more runs. Seems fairly compelling, but what factor did defense and bad luck play?

Bad Defense

Here’s a chart showing the Flops’ park-adjusted defensive efficiency in their Flop Year as well as the preceding year, when the team was quite good per my Flop requirements above.

| Team | Pre-Flop Year PADE | Flop Year PADE |

| Philadelphia | .75 | -.27 |

| Boston | -.60 | -1.83 |

| Washington | -.76 | .07 |

Both Boston and Philadelphia were below average defensive teams in 2012. However, Philadelphia is the only team of those two that experienced a significant change in defensive efficiency from the previous year, falling from being a top 10 team in 2011 to near the bottom in 2012. Boston was a below average defensive team in 2011. Washington, on the other hand, went from being a below-average defensive team in 2014 to average in 2015. No clear relationship here, though bad defense doesn’t help.

Bad Luck

Looking at 1st Order Wins, or the number of wins each team SHOULD have won based on the difference between runs scored and runs allowed, gives us a sense of how lucky or unlucky these teams were. Washington was the most unlucky, at 5.5 wins behind their 1st Order Expected Wins. The average “miss” that year was 4 wins on either the win or loss side, so Washington was not afflicted with a plague of particularly bad luck compared to other teams. The other Flops were less unlucky than that. None of these teams were particularly unlucky.

As a result, I lean towards injuries to starting pitchers, and bad replacement pitchers, being the primary culprit for the Flops.

How could the Cubs flop in 2017?

The Flops met their sad ends as a result of their starting pitchers missing extended time due to trades or, more likely, injury. So this is a concern for the Cubs generally, but also specifically for this team based on the makeup of the starting rotation.

The Cubs starting pitchers average 30.4 years in age, with Lester and Lackey well on the wrong side of 30. This group has been incredibly durable for the past several seasons, but no pitching staff has consistently been THAT durable for multiple years, as examined by my BP Wrigleyville colleague, Sam Fels. His astute analysis makes me think the Cubs starters are very likely to miss more starts this year than last, perhaps many more if their injury luck runs out, into the yard, out of the gate, and into oncoming traffic.

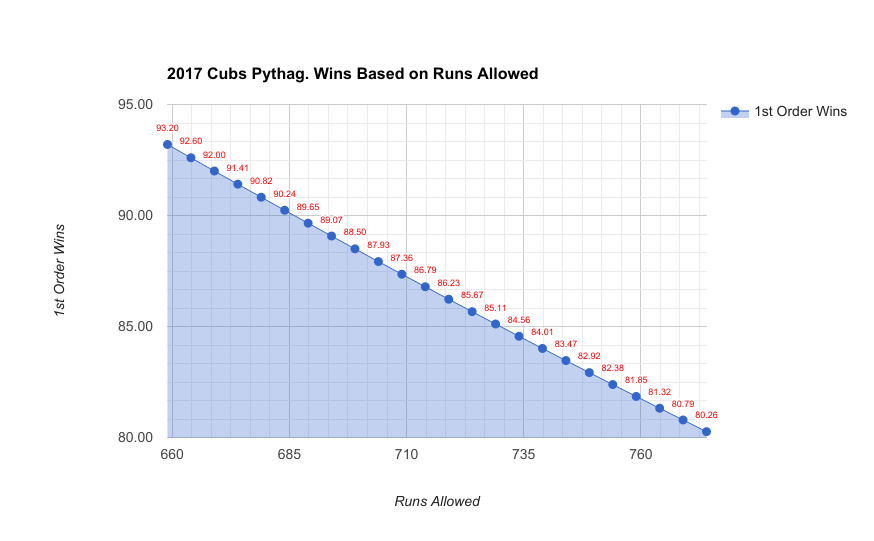

The Cubs’ front office seems aware of this potential risk, as evidenced by their stated focus on young starting pitching this offseason, the Brett Anderson, Eric Butler, and Alec Mills deals, and perhaps by the recent comment by VP of Scouting and Player Development Jason McLeod on 670 TheScore that “[t]he reins are off” starting pitching prospect Dylan Cease. How any of the replacement starters perform if called upon is hard to project. We can, however, project how the team’s expected wins would drop if they surrendered more runs. For this purpose, I kept the current PECOTA projection for runs scored/defense, and calculated the Cubs’ 1st Order Expected Wins while increasing their runs allowed in 5-run intervals:

At just 25 more runs allowed, the Cubs 1st Order Win expectation drops to 89 wins, which, if you trust PECOTA, has them winning the NL Central but being the worst team making the playoffs. At 50 more runs allowed, they probably join the venerable ranks of the Flops and may miss the playoffs if the Cardinals play slightly better than PECOTA projections whiling tapping into their eternal reserves of evil luck. Beyond that, I curl up into a ball in the corner to sob, mumble, and rock myself.

How many missed starts result in 25 or 50 additional runs allowed? It’s hard to say. But should more than one of the Cubs starters go down due to injury, or any one of them sustain an injury requiring a prolonged absence, I’ll be sweating bullets like I mistakenly doubled down on a hard 15.

Lead photo courtesy Jerry Lai—USA Today Sports

Good piece. I think the bullpen and rotational depth relies heavily no high-risk and high-variance players. I’m not critiquing the methodology, but when we look at guys like Koji (42 years old) or Duensing (13 IP last year) or Davis (arm) or others, it is reasonable to find a flaw with each guy. I don’t think it is a tick-tacky thing, either; our arms are loaded with guys who have historically been great or are good buy-lows, but all of them feel like a wide variance of outcomes. That’s my biggest concern for 2017.