In October, Dexter Fowler made history as the first black Cub to play in the World Series. Concerning that fact, Fowler said it would not have been possible without Jackie Robinson, and it was something he would carry with himself. Over the weekend, he received backlash for his innocuous comments concerning the present administration’s travel ban. Of the many predictable comments telling him to stick to sports, one in particular has received much attention for referring to Fowler as property of the Cardinals. Replying to this criticism, Fowler tweeted: “I know this is going to sound absolutely crazy, but athletes are humans, and not properties of the team they work for.” Aside from the (hopefully) obvious error of calling a black American property, the comment points to a distinct and purposeful ignorance of black America’s relationship with baseball. It is a common held belief that for much of its existence, baseball has been a white man’s sport, and while it is true that the organized baseball we follow has a shameful, colorless history, African Americans have been playing versions of the game longer than this country has existed, and each player like Fowler carries this history with him today.

Baseball as we know it today grew out of the Civil War and was championed by Abraham Lincoln, thus firmly entrenching it in American racial politics. On his deathbed, the story goes, the Civil War president and baseball fan used his few remaining breaths to tell Abner Doubleday to “keep baseball going; the country needs it.”1 While this story is obviously preposterous, it points to baseball’s early cultural and political significance. Many believe that before the Civil War, the South had little to do with the sport, and New England and Chicago preferred town ball. But as the war waged on, baseball became increasingly significant as a coping mechanism for weary soldiers and as a means of cultural unification.

Abraham Lincoln, thus firmly entrenching it in American racial politics. On his deathbed, the story goes, the Civil War president and baseball fan used his few remaining breaths to tell Abner Doubleday to “keep baseball going; the country needs it.”1 While this story is obviously preposterous, it points to baseball’s early cultural and political significance. Many believe that before the Civil War, the South had little to do with the sport, and New England and Chicago preferred town ball. But as the war waged on, baseball became increasingly significant as a coping mechanism for weary soldiers and as a means of cultural unification.

During his time in politics, Lincoln played a number of games, primarily at his home in Springfield, Illinois and on the White House lawn while in office. These accounts turned Lincoln into the ultimate fan, whose mythos included quickly dismissing news of his Republican primary victory on the grounds the message interfered with his at-bat and skipping Congressional meetings to play. During the early part of his career, Lincoln, however, played “town ball” rather than “baseball.” A mutation of the English game “rounders,” town ball was a less structured sport, played by up to 14 members per team for an unspecified number of innings with either one or upwards of ten outs per half-inning.2 Popular throughout New England and parts of the South, town ball reached its height a decade prior to the Civil War.

However, cutting-edge New Yorkers modified town ball in 1845 to create a game played by nine people per team for 9 innings and a total of 27 outs: baseball. By the late 1850s, the precursor to MLB was born, establishing the Civil War as a clash between Unionists and Confederates, town ballers and baseballers. New York soldiers began teaching it to soldiers from New England, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Ohio at the behest of generals who believed the game created morale and discipline. These soldiers then spread the game throughout POW camps in the South and Midwest, and when the war ended in April 1865, baseball games and leagues blossomed throughout the country as soldiers returned to their homes, captivating the nation with the more simplistic game of baseball.3

But this account is only the partial truth. In the South, long before the Civil War, town ball was one of the few respites for slaves. Slave owners ordinarily allowed their slaves to practice only individual sports, such as boxing and wrestling, that they could bet on and collect money when pitting their slaves against neighboring estates’.4 Some slaves, like John Finnley from Alabama enjoyed the sport, while others viewed it as merely another form of enslavement.5 Town Ball, however, was regarded much more favorably, and although it is unclear why certain owners allowed their slaves to partake in the purely recreational team sport, such instances often became slaves’ most cherished memories.

The first documented instance of slaves playing town ball is from a 1773 memo from Beaufort, SC: “We present as a growing Evil, the frequent assembling of Negroes in the Town on Sundays, and playing games of Trap-ball and Fives, which is not taken proper notice of by Magistrates, Constables, and other Parish Officers.” Then, in 1797, the North Carolina Minerva reported a penalty of 15 lashes to “negroes, that shall make a noise or assemble in a riotous manner in any of the streets [of Fayetteville] on the Sabbath day; or that may be seen playing ball on that day.”6

Through testimonials of former slaves gathered by the Library of Congress in 1940, we can see the popularity of town ball and baseball between the 1840s and 1860s. Variations of baseball were played by slaves in Texas, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Missouri, and the Carolinas. Duncan Gaines of Florida recalls “Most of the time of the slave children was spent in playing ball and wrestling and foraging in the woods…they were often joined in their play by their master’s children,” which is one of a number of similar accounts.7

Henry Baker of Alabama offers are more in-depth account of playing in the late 1850s, describing playing in large groups consisting of both slaves and white children and using a ball made out of rags.8 Ed Allen of Arkansas reaffirms this account, also stating that after the Civil War, white and black children no longer played together.9

While the Civil War marked a monumental victory for the Union and baseball, it ushered in newer hardships for black baseball. African Americans were now technically free, but found themselves still barred from much of society, including baseball. White America became determined to interact with Black America as little as possible, and segregation soon became the norm. As Ed Allen and Henry Baker alluded to, the segregation seeped into baseball.

While white baseball—or just “baseball,” as white people have rarely needed qualifiers—thrived and cemented itself as America’s Game, African American baseball led a more secretive life rarely recognized by white America. In fact, the first white reporting of black baseball was accidental in nature: “on October 16, 1862, ‘a sporting correspondent for the Brooklyn Eagle, discovering the game between two white teams that he was supposed to cover had been canceled, stumbled instead on the Weeksville Unknowns playing Brooklyn’s Monitor team.’”10

In 1867, the National Association of American Base Ball Players “unanimously reported against the admission of any club which may be composed of one or two colored persons” on the basis that “if colored clubs were admitted there would be in all probability some division of feeling whereas, by excluding them no injury could result to anybody, and the possibility of any rupture being created on political grounds would be avoided.”11 Black players were confined to independent or hotel teams who played other semi-pro teams in various predominately east coast cities like Brooklyn, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington.

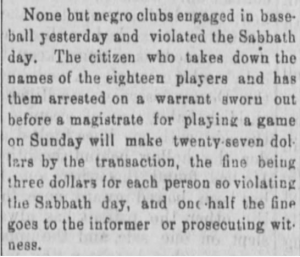

What little coverage black baseball received in white newspapers, though, wa s dedicated to framing it as a conduit for criminal activity or portraying it as a spectacle akin to a circus act. In 1869, the Memphis Public Ledger wrote about a game between a black team and a white team in Philadelphia, concluding, “the darkeys got the worst of the game, but they have won more than they lost by the social recognition they have gained.”12 In 1877, though, as civil rights protests strengthened throughout the country, the Ledger suggested turning in black people for playing baseball on Sunday, thereby violating the Sabbath. The city police offered a reward of $3 per black person arrested.

s dedicated to framing it as a conduit for criminal activity or portraying it as a spectacle akin to a circus act. In 1869, the Memphis Public Ledger wrote about a game between a black team and a white team in Philadelphia, concluding, “the darkeys got the worst of the game, but they have won more than they lost by the social recognition they have gained.”12 In 1877, though, as civil rights protests strengthened throughout the country, the Ledger suggested turning in black people for playing baseball on Sunday, thereby violating the Sabbath. The city police offered a reward of $3 per black person arrested.

By the late 1880s, a generation of African Americans born in freedom in the South had become determined to push for greater equality. Both school enrollment and voter participation increased as they realized they could use these systems to effect change. This push for equality seeped into baseball, where black players like Moses and Welday Walker (the first two black players to play in the “majors” in 1884) branched out to play on predominantly white professional teams. But as white Southerners grew wary of this push for greater equality, they legislated a series of roadblocks designed to disenfranchise and segregate African Americans. By 1888, black players were no longer allowed to play on white teams and the first attempt at an all-black league failed after they were designated purely minor league and realized no player could play for a Major League team. In 1890, the Cuban Giants–a merging of the Philadelphia and Washington teams–was the sole remaining “professional” black team.13

As both black protests and baseball teams strengthened at the turn of the century, white political and news publications tried to regain control over them by characterizing them as lawless and a threat to society. In 1903, newspapers in St. Louis reported on a incident in which “negroes used baseball bat as weapons” after a game one day and attacked a “white peacemaker” who attempted to break up a riot.14 In 1905, the New Orleans Times-Democrat wrote that the park would serve as a “rendezvous and headquarters for negro loafers and hoodlums,” thereby driving down the value of the neighborhood.15 Similar stories appeared across the country over the next two decades. Some halfheartedly claimed they were looking out for the best interests of the black players, like in Atlanta: “it was claimed that a white man was behind the project for the purpose of making money out of negroes and that such a park would cause lawless crowds to gather.”16 But the underlying motive was always apparent. White people viewed baseball as theirs and feared the ramifications of a “black takeover”; if they lost baseball, there was no telling what else they could lose.

In 1910, there was another attempt to create a black baseball league, but it failed when the owners refused to allow only black owners and their teams into the league. Over the next decade, black baseball players were largely confined to amateur teams or made members of the travelling All Nations team that played black and white teams across the country. As the country faced WWI and threats from both Native Americans and women, the plight of black baseball was pushed to the background, enabling white patrons to take pleasure in watching the All Nations team as they were no longer a particular threat.

However, as the push to create a league emerged again in 1919 and 1920, African American men used their prowess on the field as motivation to also push for equality. In 1920, the Kansas City Sun, a black newspaper, wrote, “the objective mind of the negro, bold and positive, because it has observed signal mental and physical prowess on the part of Negro players, insists that high class major league ball is highly possible for negro teams.”17 African Americans became emboldened by their efforts in the War, at home, and on the field; many were dedicated to saving American democracy, like they had saved British and French democracy.

Following the 1919 race riots in which white people attacked thousands of African Americans across the country in at attempt to force them to give up their jobs, African Americans were again seen as the enemy, labeled in many cases as Communists. Despite being unable to prevent the formation of an all-black league under Rube Foster in 1920, white Americans remained dedicated to segregation, a practice that held for 27 more years, until Jackie Robinson in 1947.

When not viewed as a threat, white Americans allowed African Americans to enjoy the fun of baseball, but whenever threatened, they fought back, attacking black baseball in hopes of marginalizing it or destroying it altogether. While black Americans have loved the game as long as white Americans, their experience has too often been dictated by their history as slaves. So when Dexter Fowler is referred to as property, it not only evokes the labor issues faced by all professional baseball players, but also baseball’s specific history of oppression. When Fowler puts on his uniform, then, the name on the back signifies the bright future of black baseball and how far baseball has come, but we should still remember the sometimes dark history of the league emblem on the sleeve.

1 Albert Goodwill Spalding, America’s National Game: Historic Facts Concerning the Beginning, Evolution, Development and Popularity of Base Ball, with Personal Reminiscences of Its Vicissitudes, Its Victories and Its Votaries, American Sports Publishing Company, 1911.

2 http://www.baseball-almanac.com/ruletown.shtml

3 http://www.pacivilwartrails.com/stories/tales/baseball-and-the-civil-war

4 Sergio Lussana, “To See Who Was Best on the Plantation: Enslaved Fighting Contests and Masculinity in the Antebellum Plantation South,” Journal of Southern History 76 no 4, 2010, pg 2.

5 Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 16, Texas, Easter-King, pg. 37.

6 North Carolina Minerva, March 11, 1797

7 Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 3, Florida, Anderson-Wilson, pg. 134.

8 Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 1, Alabama, Aarons-Young, pg. 28.

9Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 2 Arkansas, Abbott-Byrd, pg, 40.

10 Lawrence D. Hogan, “The Forgotten History of African American Baseball,” 16.

11 https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/09/23/blacks-baseball-and-the-civil-war/?_r=0

12 Public Ledger, Sept 18, 1869.

13 Hogan, 20-24.

14 St. Louis Republic, June 1, 1903.

15 New Orleans Times-Democrat, April 22, 1905.

16 Atlanta Constitution, April 3rd, 1912.

17 Kansas City Sun, October 16, 1920.

Lead photo courtesy David Richard—USA Today Sports

Great concise history of the origins black baseball!

Great, informative article. Well done!