On October 13th, 1921, Edna Vaughn phoned the police to file a missing persons report for her husband, James “Hippo” Vaughn. His disappearance was dated as October 8th, five days prior to the phone call. But the truth of the matter is Hippo Vaughn began disappearing months earlier, beginning April 24th, 1921.

Previously the ace of the Cubs, Vaughn signed a contract with the team in the offseason, completing what was projected  to be the league’s strongest rotation. Vaughn had joined the Cubs in 1913, and over his eight year career with the team, he earned the label of “one of the real dependable heavers” in the game, as well as the best lefty pitcher in the league.1 Though 1920 had been a bit disappointing for Vaughn and the team as a whole, after a solid spring training, Vaughn and the Cubs began the season full of promise.

to be the league’s strongest rotation. Vaughn had joined the Cubs in 1913, and over his eight year career with the team, he earned the label of “one of the real dependable heavers” in the game, as well as the best lefty pitcher in the league.1 Though 1920 had been a bit disappointing for Vaughn and the team as a whole, after a solid spring training, Vaughn and the Cubs began the season full of promise.

His season began on a shaky note, however, as he gave up seven runs to the Cardinals in an 8-7 victory. After winning two of the next three games to start 3-1, Vaughn hurtled into a string of seven losses mixed with two no-decisions. His next victory on June 22nd against the Cardinals was the last of his career. In May, the Cubs tried to trade the washed up pitcher to Cincinnati in exchange for third baseman Heinie Groh, but the Reds refused, arguing Vaughn’s career was all but finished.2

On July 9th, Vaughn pitched against the league-leading New York Giants in New York. Through the first three innings, he pitched perhaps as well as he had at any point that season, only surrendering one run on two hits and a walk. Had the game ended then and there, the season would perhaps have been far kinder to the beleaguered pitcher. Alas, the game continued into the fourth. With a 2-1 lead, Vaughn retired the first batter of the inning. The next two reached on singles, and Vaughn walked Johnny Rawlings to get to Frank Snyder, the catcher, who was more of a ground ball hitter. Except in this at-bat. Snyder walloped Vaughn’s pitch over the left field fence, driving in four runs. Vaughn, “grim with disgust,” served up a home run to the next batter, pitcher Phil Douglas. Having seen enough from the struggling veteran, Johnny Evers lifted Vaughn from the game.3

Two days later, the New York Times reported that Vaughn had all but disappeared. Nobody from the Cubs had spoken to him since his disastrous start, and if he did not return to the team, he would be suspended indefinitely. Though there were unsubstantiated reports of Vaughn returning to Chicago on July 15th, his career with the Cubs was finished. He was handed an official suspension of 30 days.

Despite nine years of goodwill and and a multitude of deficiencies of the 1921 Cubs to write about, newspapers immediately chastised Vaughn for his actions. On July 21st, the Sporting News wrote that Evers was forced into suspending Vaughn. The Times Herald accused Vaughn of deserting the Cubs. The Evening Journal applauded Evers for his swift response, stating, “no ballclub can make headway without discipline.”4 Additionally, the New Castle News labeled him a “temperamental left hander” and several papers insinuated Vaughn’s erratic behavior was caused by a drinking problem.5

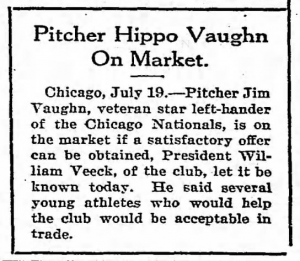

At the beginning of August, the Cubs replaced Evers with Bill Killefer, the team’s catcher. Some, like the Janesville Daily Gazette, speculated the switch could lure Vaughn back to the team as the two players were fond of each other. Addressing the situation, Veeck asserted the ball was in Vaughn’s court; if he wished to play for the team, he must arrive on August 9th in playing condition.6

Vaughn, however, had no intention of returning to the club that had spent the past month humiliating him. Toward the beginning of his suspension, Vaughan requested to be traded to another club where he could have a fresh start. Veeck acquiesced, on the condition Vaughn negotiate the deal himself and ensure the Cubs received more than they would were they to place him on waivers.7 Perhaps due to his reputation or his abysmal play, Vaughn was unable to secure a deal with any other major league club. This was likely uns urprising news for Veeck, who, in May, tried to trade the washed up pitcher to Cincinnati in exchange for third baseman Heinie Groh, but the Reds refused, arguing Vaughn’s career was all but finished.8

urprising news for Veeck, who, in May, tried to trade the washed up pitcher to Cincinnati in exchange for third baseman Heinie Groh, but the Reds refused, arguing Vaughn’s career was all but finished.8

The prideful man refused to return to Chicago, instead signing a 3-year, $20,700 deal with the Fairbanks Fairies, a semi-pro team based in Beloit, Michigan. The deal enabled him to play baseball on the weekend while working for the Fairbanks-Morse company during the week. After catching wind of this signing, Major League Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis suspended Vaughn indefinitely, claiming he had “aligned himself with an outlaw club, which employs ineligible players and plays games against outlaw clubs.”9

Vaughn’s attitude set off a number of 1920s style thinkpieces concerning players’ effort. The Chicago Tribune wrote, “the whole trouble is that the Cubs have a few lazy, puffed up, could be good if they wanted to ball players who laid down on John [Evers] almost as clean as the Black Sox did on Comiskey,” and “ninety-nine out of 100 fans believe Vaughn could have won twice as many games if he had half way tried.”10 He was further diagnosed with having an “indifferent attitude” that hindered his performance. 11

These condemnations of Vaughn joined the chorus around the country. Americans, it was decided, were entirely too lazy. Predicting the language used against Vaughn, the Rev. William Barton of the Freeport-Journal Press wrote, “Laziness is not simply an undesirable habit. It is a betrayal of trust.”12 People in Oregon were told they were too lazy to use new indoor plumbing, and the American diction was chocked up to laziness.13 It was a blanket diagnosis for every perceived problem across the country, and it left Vaughn trapped in a hailstorm of accusations.

Though he overcame his laziness to recapture some of his magic with the Fairies, compiling an 11-1 record with 99 strikeouts and an ERA around 2, Vaughn was denied reinstatement in the Majors.14 His final pitching appearance in Chicago came on October 8th, 1921, the day he disappeared. But the story of his disappearance extends in both directions beyond that day. If April 24th or July 9th had gone differently, or if newspapers had not exacerbated the dispute, Hippo Vaughn would perhaps have clung on to a career long enough to be in the Hall of Fame. Instead, his two short disappearances in 1921 have all but erased him from baseball memory.

1 Oakland Tribune, March 30, 1921.

2 The Cincinnati Enquirer, May 25, 1921.

3 The Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1921.

4 The Evening Journal, July 16, 1921.

5 The New Castle News, august 10, 1921; and Chicago Daily Tribune, July 10, 1921.

6 Janesville Daily Gazette, August 5, 1921.

7 The Times Herald, August 3, 1921.

8 The Cincinnati Enquirer, May 25, 1921.

9 The Daily Chronicle, August 10, 1921.

10 The Chicago Daily Tribune, August 14, 1921.

11 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 14, 1921.

12 Freeport-Journal Press, January 8, 1921.

13 Oregon Daily Journal, August 24, 1921; and Pittsburgh Daily Post, March 13, 1921.

14 https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/4019283d

That last footnote is also a good read — https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/4019283d

He should be better remembered than he is.

So did he re-appear?