The question of what constitutes human happiness is one that has attracted the attention of many philosophers throughout history. The Ancient Greeks understood it by the term eudaimonia, the combining of the words “good” and “spirit,” and though there was no real consensus of how to achieve it, they generally believed, as Aristotle stated, that it was concerned with “a virtuous activity of soul.”1 The moderns, like Hobbes and Locke, understood human happiness as largely the freedom from pain or fear of death, which could be achieved through the accumulation of goods and creation of civil society with positive law. As philosophy progressed into the 20th century, philosophers looked at happiness as something less obtainable, more fleeting, and less the moral aim of the individual. Nonetheless, the question of happiness—what it is and how it should exist in society—remained central to the discussion of humanity.

In baseball, we often struggle to address questions of happiness, and they are frequently tossed aside by athletes who are tired of being asked whether they’re happy with their performance that day or season. For many, it’s not about individual happiness, and discussing it in such terms seems absurd. In a sport that breeds immense passion, there’s an underlying nihilism to baseball, particularly in fans of teams in lengthy losing streaks. They, like these athletes, want to put aside the question of happiness, precluding themselves from thinking about their team in such a term. But the question of happiness persists and is often tied to success; fans of good teams are happy while fans of bad teams are sad. But sometimes this is not the case. Sometimes, we have to dive deeper into the question of happiness. And the best place to begin such an exploration is with the 1969 Cubs.

The 1969 Cubs began the season with much promise, after having finished third in each of the previous two seasons, a marked improvement over recent years of finishing eighth through tenth. The team addressed one of its glaring needs with the offseason acquisition of bullpen pitchers Ted Abernathy and Hank Aguirre, each of whom excelled with Cincinnati and Los Angeles, respectively, and looked to aid Cubs’ closer Phil Regan in making the team’s bullpen the best in the league. The starting rotation also looked incredibly strong, with ace Ferguson Jenkins joined by Bill Hands, Ken Holtzman, and the newly acquired Dick Selma. The offense, bolstered by (a hopefully rejuvenated) Ernie Banks, Glenn Beckert, and Billy Williams, was poised to repeat its success, and if the team could figure out how to win on the road, the experts predicted they would rival the Cardinals for the newly-formed NL East division title.2

The team got off to a hot start, winning 11 of their first 12 games, and for much of the season, they looked unbeatable. With this much improved on-field product came a reinvigoration of Cubs fans, who routinely packed Wrigley for the first time in over a decade. The outfield bleachers crowd—affectionately titled the “Bleacher Bums”—invigorated the crowd each game with heckles of opposing teams and encouraging chants, like “14, 11, 18, 10: come on, infield, do it again!”3 It had been a long time since Wrigley had felt such energy, and the team and fellow fans largely welcomed it.

By the beginning of July, the team had accumulated an 8 game lead over the second-place Mets, and they looked almost unbeatable. Games had become true events in the city, dr awing in immense crowds of all walks of life, from families to college students to elderly fans excited to revive the passion for the team they had held in their youths. Homemade banners and picnic baskets constantly littered the stands, and they often brought this enthusiasm in droves to Montreal, St. Louis, New York, and every other city in which the Cubs played. Many players, including the Cardinals’ Mike Shannon, remarked that these road crowds always outnumbered their own fans, and it was difficult to walk down the street without seeing a “Cub Power” bumper sticker.4 For the first time in ages, Cubs fans believed their team was capable of something special, and they wanted to be part of it, too.

awing in immense crowds of all walks of life, from families to college students to elderly fans excited to revive the passion for the team they had held in their youths. Homemade banners and picnic baskets constantly littered the stands, and they often brought this enthusiasm in droves to Montreal, St. Louis, New York, and every other city in which the Cubs played. Many players, including the Cardinals’ Mike Shannon, remarked that these road crowds always outnumbered their own fans, and it was difficult to walk down the street without seeing a “Cub Power” bumper sticker.4 For the first time in ages, Cubs fans believed their team was capable of something special, and they wanted to be part of it, too.

As July gave way to August, the Cubs were the favorites of many to win the World Series, but things changed, slowly, imperceptibly at first, and then the team was swept up in an avalanche of defeat they had no hope of escaping. August turned into September, and the inexperienced team saw their lead dwindle to five games. And then, in the span of six games—four losses against Pittsburgh and two against the Mets—the Cubs were in second place.

Manager Leo Durocher had relied increasingly on his best players, refusing to give them off days and consistently berating them for their diminishing play, and they began to break down, compiling a shocking series of miscues over the final weeks of the season. After one rough start against the Phillies in which he threw the ball to an empty third base, Dick Selma was so afraid of the wrath of Durocher that he hid from his manager. This fear and overuse impacted the team’s confidence and performance, and as fans became increasingly frustrated with the slide—some mailed back autographs they had received from the players earlier in the season—the players became more disheartened and the losses piled up, creating an inescapable cycle.5

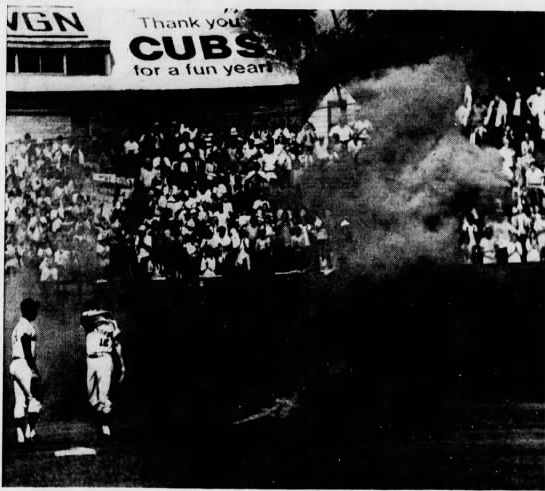

On September 19th, the Cubs—now four games behind the Mets—played the Cardinals in a doubleheader. The team won the first game 2-1, powered by a ten-inning effort from Holtzman, his best start of the season. The second game began just as promisingly, and it seemed like the Cubs really could pull off the sweep, but then an overworked bullpen and an exhausted defense coughed up five runs in the final three innings to lose 7-2. Repulsed by this turn of events, the crowd at Wrigley swapped their disappointment for blind rage, the crowd engulfed the field in trash, and one particularly daring Bleacher Bum tried to steal second base.6

This brief descent into chaos reinvigorated the fanbase, which began filling Wrigley again. Though the team’s performance did not follow suit, losing the division to the Mets and finishing 8 games back, thousands of fans continued to flock to Wrigley during the final few meaningless games of the season. Even amidst reports that the players became too conceited and money-oriented at the behest of fans, looking for happiness anywhere but on the field, a solid contingent of fans continued to demonstrate their appreciation for the team.

At both of the team’s final games—home games against the Mets—were 10,000 fans there purposefully to applaud the team and thank them for the summer. The farewell was orchestrated by a number of fans and sports columnists, each of whom wanted to reclaim Cubs fandom from those who had abandoned the team that month and demonstrate their gratitude to the players. As one fan put it, this Cubs team “gave [them] an opportunity to enjoy [their] summer more fully than ever before,” and they should continue to derive great joy from it.7

As a team slated to be a World Series contender for much of the season, the failure to make the playoffs should have been disappointing, the spoiler to a very nice season, and for many, it was. But others looked past the collapse to find happiness in different moments, to eschew the conventional understanding of success. It is difficult to determine whether there exists, as the Ancients thought, any virtue in this form of happiness, or if it is completely self-involved, as suggested by the moderns. But it nonetheless is a happiness that exists, and perhaps one that signals that regardless of the outcome of our team’s season or playoff aspirations, we can each find our own happiness and understand that success is not necessarily good and failure is not inherently bad.

Lead photo courtesy Dennis Weirzbicki—USA Today Sports

Notes:

1 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, book 1, ch. 9.

2Warren Times-Mirror, March 11, 1969; Port Angeles Evening News, March 24, 1969; Dixon Evening Telegraph, April 3, 1969.

3Stuart Shea, “Wrigley Field: The Long Life and Contentious Times of the Friendly Confines,” Revis ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 298-300.

4 Chicago Tribune, July 8, 1969.

5Doug Feldman, “Miracle Collapse: The 1969 Chicago Cubs,” (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), 215-220.

6Ibid, 223-225.

7Chicago Tribune, October 1, 1969.