On January 31st, 1898, writing about Cap Anson’s retirement from baseball, the Chicago Tribune declared, “an epoc of baseball is finished,” and, like the great prophets, Anson was “left without honor in his own land.” Though the decade obviously continued for another two years, the 1890s Chicago baseball team was, in the eyes of the newspapers, almost wholly defined by Cap Anson and thus ended with Anson’s departure. As a whole, the decade was mired by a downturn in baseball’s popularity, largely attributed to the NL’s schism and the sport’s lack of a clear identity. Anson and his band of youthful players, named the Chicago Colts from the nickname “Cap’s Colts,” hoped to re-energize Chicago fans and continue the success for which the team had become known.

The Decade At A Glance

In 1890, after a mass exodus of players to the short-lived Players’ League, where they hoped they could be fairly compensated for their work, each of the NL teams was forced to bring in new faces to replace the old stars of the ‘80s. Leaving Chicago were Ned Williamson, Fred Pfeffer, Silver Flint, John Tener, and Frank Dwyer, making Anson the sole veteran. Among these players brought in to fill out the now sparse roster were catcher Malachi Kittridge, second baseman Bob Glenalvin, shortstop Jimmy Cooney, left fielder Walt Wilmot, and pitcher Pat Luby. The cadre of young players were quickly dubbed “Cap’s Colts,” a name that stuck throughout the decade despite its later absurdity.

The team started the decade strongly, finished behind only Brooklyn in 1890 and Boston in 1891. However, the remainder of the decade’s teams fared much worse, finishing in 9th twice and peaking at 4th in ‘95. The folding of the Players League and American Association incorporated four more teams into the league in 1892, theoretically offering the Colts an opportunity to continue their dominance, particularly with the acquisition of American Association star pitcher Clark Griffith, who promised to replace worn out veteran Bill Hutchinson.

But the young team began to falter against more seasoned competition, displaying poor skills in all aspects of the game. Though fans continued to watch the team, never allowing the Colts to dip into the bottom half of league attendance, the franchise did not make it easy for them to do so, frequently switching between South Side Park and the slightly smaller but newer West Side Grounds throughout much of the decade, and finally settling into West Side Grounds in 1895 after it had been rebuilt following a fire.1

By the end of the decade, the youth of the team had been replaced with weariness and disappointment as Anson’s staunch traditionalism and racism prevented it from matching the rapidly evolving game. He demanded loyalty from his players and held grudges against all those who had migrated to the Players’ League, particularly the Irish Jimmy Ryan, who drew much of Anson’s ire with fellow Irishman Malachi Kittredge. The longer Chicago went without winning, the more paranoid Anson became, and by his final season, he began to suspect that his players were conspiring to oust him. He set out to retaliate.

His prime target was Fred Pfeffer, who, in addition to playing in the Players’ League, had tried to resurrect the American Association in 1895 and subsequently received a lifetime ban that was overturned by a 10,000-signature fan petition. Anson had initially seen his sale to the Louisville Colonels in 1892, but Pfeffer returned to Chicago in 1896 due to a rash of injuries, sowing the seeds for the final battle between the two longtime teammates. Pfeffer, resenting Anson’s strict managing, and Anson, resenting Pfeffer’s existence, battled each other throughout much of the season. Pfeffer, by then 37, underproduced just enough to give Anson the opportunity to release the second baseman. Anson did just that following a 36-7 trouncing of the Colonels on June 29th. Many writers sided with Pfeffer, calling him the “king of second basemen” and “the greatest second baseman the game has ever known,” while suggesting Anson had reached his limit with the team.2

The Decade In A Game: June 30, 1897

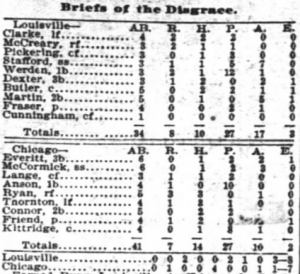

The Colts came into the game in 11th place, 20.5 games behind first-place Boston and 2.5 games behind 10th place Louisville Colonels. The releasing of Pfeffer tainted the previous day’s astounding victory, however, and many believed Anson would have to reel  off a string of such victories to remain in good favor with the Chicago baseball world. Though the game itself was a rather standard affair, it was a disappointing 8-7 loss for Anson’s team that newspapers spun into an abject catastrophe for the floundering team. Indeed, the Chicago Inter-Ocean declared that we should “take them out and drown them!” for their performance that day.3

off a string of such victories to remain in good favor with the Chicago baseball world. Though the game itself was a rather standard affair, it was a disappointing 8-7 loss for Anson’s team that newspapers spun into an abject catastrophe for the floundering team. Indeed, the Chicago Inter-Ocean declared that we should “take them out and drown them!” for their performance that day.3

In the second inning, Chicago opened the scoring as veteran right fielder Jimmy Ryan reached base then came around to score on a passed ball, wild pitch, and groundout. The Colonels retaliated in the third, taking a 2-1 lead after third baseman–and Anson favorite–Bill Everitt missed a throw from Kittridge and pitcher/“man-killer” Danny Friend was too late on his throw home.4 The Colts again took the lead in the fifth inning, as four runs came across on a walk, error, and four consecutive singles from Ryan, center fielder Walter Thornton, second baseman Jim Connor, and Friend.

The teams exchanged runs in both the seventh and eighth innings, setting up a supposed spectacular ninth inning with a “complicated case of ball playing.”5 Louisville quickly got two men on, bringing the tying run to the plate in the form of left fielder Bert Cunningham, who promptly struck out on three curveballs. The relief did not last long, though, as the following three hitters gave the Colonels an 8-6 lead. But the Colts were not without tenacity, instantly putting runners on second and third in the bottom of the inning, and cutting the deficit to one on a Connor lineout to second. Following a walk and an error to load the bases for the demoralized Everitt, who had thus far made two errors and recorded only one hit in five at-bats. Everitt patiently waited for the pitcher to fill the count before taking a wild swing at a pitch down the middle, popping the ball up to short for the second out of the inning. Shortstop Barry McCormick followed with a similar at-bat to end the game and seal Anson’s fate.

The Aftermath

Though Chicago improved in the remaining months to finish ninth, the team still finished 34 games back of Boston and both the Inter-Ocean and the Tribune, Chicago’s largest newspapers, occupied themselves debating Anson’s future with the team, unleashing every known baseball cliché in the process. Those in favor of Anson as manager asserted their opposition must have never played the sport, while those in favor of his retirement charged him with actively weakening the team with both his play and management. As the season progressed, the latter gained volume, and Anson reluctantly conceded his retirement after 22 years with the team.

Without Anson, the ‘98 and ‘99 teams were at a loss and newspapers were at a loss on how to cover them, eventually dubbing them the “Orphans.” Taking over for Anson was Tom Burns, who, behind the strong play of Ryan and Griffith, managed the team to a fourth-place finish in ‘98, but the success did not continue for the team as Griffith struggled with arm soreness and the offense could not compensate for the downturn in pitching. After two seasons, Burns was fired, and Chicago ended the decade directionless and without identity.

1 Peter Golenbrook, “Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs,” (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), 36-42.

2 Chicago Inter-Ocean, July 1, 1897, pg. 5.

3 Ibid.

4 Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1897, pg. 4.

5 Ibid.

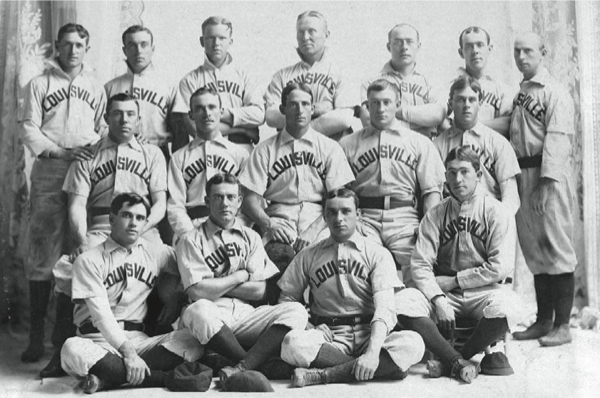

Lead photo courtesy Society for American Baseball Research, http://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-29-1897-chicago-colts-record-romp-36-runs