With one out in the fifth inning on Saturday, Joe Maddon exited the dugout and strolled to the pitcher’s mound. The Cubs skipper was about to pull José Quintana after only 83 pitches and the game tied at three, despite the bullpen’s generally overworked state. It was a contentious move, and there was a bit of consternation among Cubs fans who thought that Quintana was pitching solidly despite a few mistakes.

Was there truth to this, though? Was Quintana pitching well? It’s a more difficult question to answer than it seems, as two of the five hits Quintana allowed were dinky doubles by Gorkys Hernández, and the lefty did not have an opportunity to escape the fifth-inning jam. There’s a good chance that, if he were left in the game, Quintana would have surrendered even more runs; since that inning was the game’s inflection point, Joe Maddon made an aggressive decision to try to stem the flow of hits and runs.

However, I think Saturday’s start provides us with some useful information regarding Quintana’s 2018 performance: who he is right now, what’s wrong with him, how he can make himself right again.

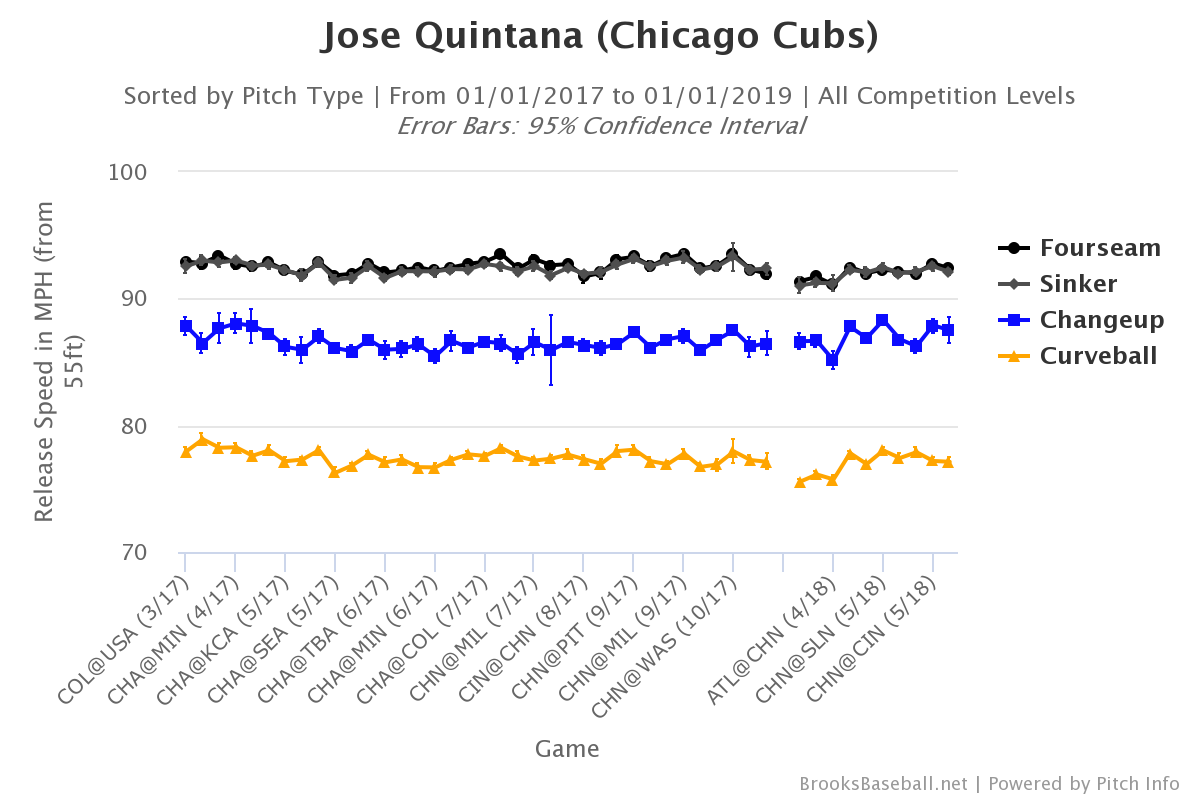

Let’s start with a graph that shows something encouraging. Much early season concern has focused on Quintana’s fastball velocity, which has been down a tick from his usually consistent 92 mph.

This is a game-by-game chart of Quintana’s average velocity on his four currently used pitches. One can easily see his velocity dip at the beginning of 2018 after preternaturally consistent marks throughout 2017, and one can also see that Quintana’s fastballs—he throws his four-seam and two-seam varieties at near identical velocities, a rare quirk—have slowly come back to normal. In fact, in his last two starts, Quintana has averaged 92.79 and 92.39, respectively, on his four-seamer, in line with his recent career marks. That’s good! Quintana is clearly regaining some liveliness in his arm, and he’s continuing to strike hitters out at a higher rate than any of Jon Lester, Kyle Hendricks, and Tyler Chatwood. His 21.9 percent strikeout rate is down five points from last year, but it’s also right in line with his career 21.0 percent mark.

Quintana struck out six hitters on Saturday. They all came in the first three innings, though, as the last four outs he recorded were on balls in play. A couple of those balls were struck rather well by Giants hitters, indicating the faltering effectiveness of the lefty nearing the end of just his second time through the order. By the time the top of the Giants’ lineup toed the batter’s box the third time, they had Quintana squared up, and this is likely why Maddon decided to bring in a fresh arm.

How could this happen to a veteran hurler with a long track record of success? This type of start has been common for Quintana this year: in 10 total starts, he’s had three clunkers (six-plus runs), three stellar outings (one run or fewer), and four outings in which Maddon has pulled him before the damage became insurmountable, usually in innings four, five, or six. This last category includes Saturday’s start. For some insight, let’s look at Quintana’s early success compared to his middle-inning struggles.

In the second inning, Quintana struck out the side. The lefty executed perfectly versus Brandon Crawford, getting two called strikes on four-seamers down in the zone before throwing two four-seamers out of the zone, both of which Crawford took. Finally, Quintana threw a two-seamer at the knees to catch Crawford looking. Crawford didn’t swing at any of the five pitches, but Quintana was able to throw a quality strike on 2-2 after failing to induce a swing at a pitch out of the zone.

The very next hitter, Nick Hundley, found Quintana in a very different mood, showing the Cubs starter’s different approaches versus lefties and righties. Quintana started Hundley with a curveball for a called strike, a very effective weapon for the lefty, and followed with a changeup down and away, at which Hundley swung and missed. Once again, Quintana went to his fastballs for his out pitches, throwing a four-seamer off the plate inside that Hundley took for a ball. Quintana then threw a two-seamer in the zone that Hundley fouled, and finally came back with a curveball down to catch Hundley swinging. Quintana failed to get Hundley on his four-seamer, but he set up well for a curveball strikeout.

Finishing his trio of strikeouts in the second was relatively easy for Quintana against the hapless Kelby Tomlinson, and Quintana challenged Tomlinson with a high four-seamer, a meaty four-seamer that Tomlinson swung through, a curveball in the zone for a called strike, and finally another four-seamer that caught all of the plate and which Tomlinson missed. Through these three plate appearances, we can get a sense of how Quintana likes to attack hitters, and that his approach features loads of fastballs. Versus Crawford and Hundley, he attempted to get them to chase four-seamers out of the zone, but neither was tempted. Versus Tomlinson, he challenged with fastballs because the righty isn’t a good hitter, and as a result, he didn’t nibble at the edges and miss the corners as he might with a better hitter.

About those better hitters… In subsequent at-bats, as the lineup finished for the second time and turned over for its third go-through, Quintana didn’t execute his plan as well, and that showed up in the box score. Take Mac Williamson’s fourth-inning walk. Quintana quickly got ahead of Williamson 0-2 after a four-seamer for a called strike and a curveball down that Williamson fouled. He then threw four straight balls to the Giants outfielder, missing with a high fastball, a curve in the dirt, a four-seamer off the plate outside, and a two-seamer off the inside corner. Williamson, like the previous hitters, was not tempted by Quintana’s fastballs that were out of the zone.

Crawford then stepped in, and Quintana once again got two quick strikes on a curve and four-seamer in the zone—a swinging strike and foul ball, respectively. But then, Quintana became shy: he threw a curve in the dirt, a two-seamer wide of the zone, a four-seamer wide of the zone, and another two-seamer off the plate inside that Crawford got a piece of. Again, Quintana went from 0-2 to 3-2, and when he tossed Crawford a belt-high fastball, Crawford pounded it for a homer.

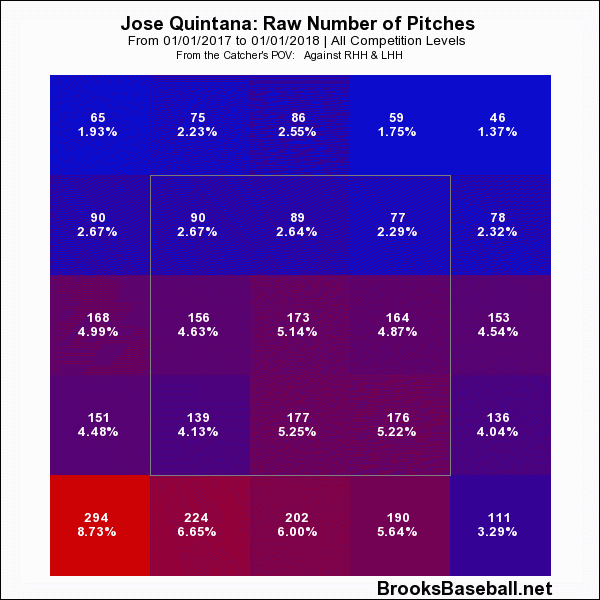

These are the hallmarks of 2018 José Quintana. For better visual representation, his zone profiles for 2017 and 2018:

Quintana has thrown more pitches to the bottom of the zone so far this year, but he’s also missed low more often this year. The lefty is also failing to get the ball down and inside to righties and down and outside to lefties, which can be seen in Quintana’s zone profile broken down by handedness. If we’re running with the hypothesis that Quintana is not tempting hitters to swing at pitches out of the zone, this is supporting evidence; Quintana is more predictable in his pitch placement this year, and that’s most likely not by design.

After looking at this granular stuff from Saturday’s start, we can pull back and place these observations in the larger scheme of Quintana’s 2018. Quintana’s problems this year have been his increased walk and home run rates, a dangerous tandem that, intuitively, has led to a few very unsightly lines for Quintana. So far this year, he’s walking hitters at an alarming 11.6 percent rate, a 75 percent increase from his career rate, and allowing home runs on nearly 15 percent of flyballs, compared to his 9.7 career mark. Those are… bad. Why is Quintana walking so many and allowing so many homers, though?

The key is his pair of fastballs. Quintana has always been a pitcher who thrives on locating those pitches with precision, and over the past year and a half, we have seen some changes in Quintana’s fastball. The first change is with his usage of the pitches: when Quintana came to the Cubs last summer, he began to throw a lot more two-seamers than in the past, surpassing his four-seam fastball as his primary pitch. That trend disappeared this season, as the lefty went back to throwing his four-seamer more often. In April, Quintana threw his two-seamer less often than in any month since summer of 2015! Clearly, Quintana felt the need to move back to his more firm fastball variant.

That might be a sound strategy if hitters were biting at the pitch. However, as Quintana has thrown more four-seamers, hitters have begun to lay off the pitch, as evinced by the Giants’ at-bats covered above. Hitters have swung at only 40 percent of four-seamers from Quintana this year, down five points from last year; Quintana has thrown 38 percent of four-seamers for balls as a result, a four-point increase from 2017. Not coincidentally, the same trends hold true when examining Quintana’s two-seamer. It’s a deadly combo.

For a quick and dirty example of how this has affected Quintana’s game, we’ll turn to the outcomes produced by those pitches. Each fastball has seen a jump in ISO this season, and Quintana has already walked 12 hitters on four-seamers this year—the same amount as 2017, the result of his desire to throw the pitch more and his inability to induce swings. He’s also already allowed four homers on the four-seamer, compared to last year’s five. Clearly, Quintana’s key pitches are not serving him well, and throwing the four-seamer more often is only compounding his problems.

It’s a rather difficult problem to solve, since Quintana doesn’t appear to be faltering mechanically or releasing the ball at a different height or angle. That the Cubs lefty has already upped his velocity to career-average marks could be a sign that his fastball command will improve, as he regains a feel for the pitch. Quintana might be better served upping his two-seamer usage and cutting back on the four-seamer, at least for the time being, in an effort to find the edges of the zone more often. After all, if the hitter has reason to believe the fastball you’re throwing is going to be a ball, it’s easier to wait for one that will be in a hitter’s wheelhouse.

I harbor a conservative optimism that Quintana will bounce back. It’s unlikely that the pitcher the Cubs acquired last summer has vanished, and that this is the new version of Quintana that Chicago will see for the next few years. Quintana has a track record of sustained success that is too long, and convincing oneself that a few bad starts in the first third of a season are the new normal is foolish. But Quintana needs to command his fastball, and he needs to cut down on walks, and he needs to limit home runs. Finding the corners of the plate more often with his fastballs, keeping hitters from sitting on pitches in the zone, and not falling behind hitters by throwing so many fastballs wide of the plate in pitcher’s counts should all aid in the correction of Quintana’s rate stats. If he can do that, the Cubs will have a much better opportunity to make good with their NL-best offense.

Lead photo courtesy Matt Marton—USA Today Sports