The truth about contending teams’ bullpens is that very few of them remain the same throughout a season. The easiest thing to add at the trade deadline is an extra relief arm, and the easiest guy to displace to make room for any addition is the last guy in a bullpen, but that’s only part of it. The rest is a mixture of fundamental truths about relief pitching, from an on-field perspective:

- Relievers run hot and cold, and teams—field staff and front office alike—are inclined to play the hot hand. That’s not necessarily a bad way to do business, either. There’s a certain logic to embracing variance, when variance is inescapable.

- Under the current paradigm of pitcher usage in MLB, it’s hard to keep an entire bullpen fresh. It’s often necessary and advisable for a team to artificially keep a pitcher out of a few games, or to enforce upon themselves a lighter workload for a given arm, even at the expense of optimal deployment. That forces the guys a few rungs down to step up and handle not only more innings, but more important ones. That shuffling can become permanent, depending upon how everyone involved responds to the changes.

- Relief pitching is a difficult task, with an unpredictable schedule both from day to day and within games. It may be easier for relievers to get batters out, but their uneven usage and the demands of the job these days (namely: you’d better throw hard, and have something nasty with which to miss bats, and it’d better show up at full strength from the moment you enter the game) lead to a higher injury rate among relievers. As a result, there’s often significant turnover that happens simply out of necessity.

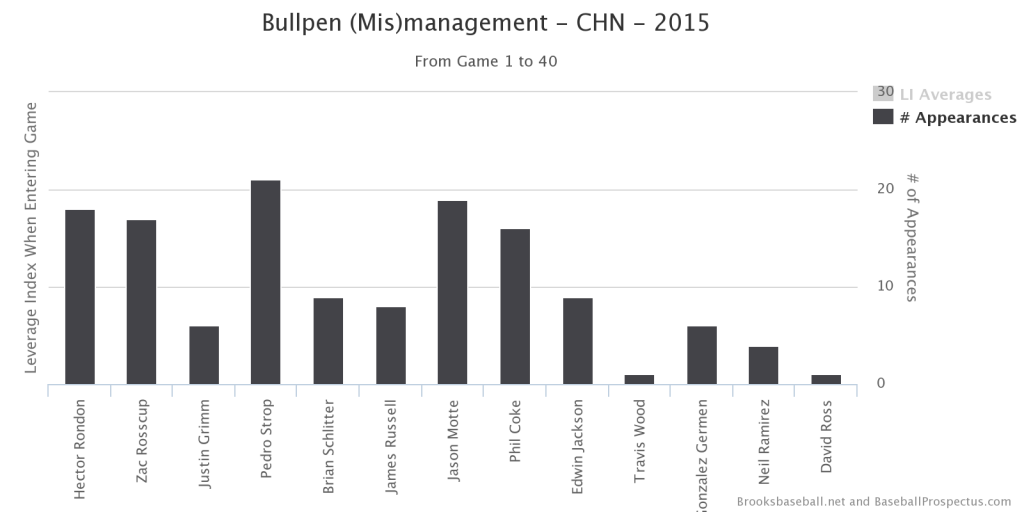

The Cubs’ bullpen, of course, has already undergone a good deal of turnover. Using Baseball Prospectus’s Bullpen (Mis)Management tool, I can show you this chart of the Cubs relievers by appearances during the season’s first 40 games:

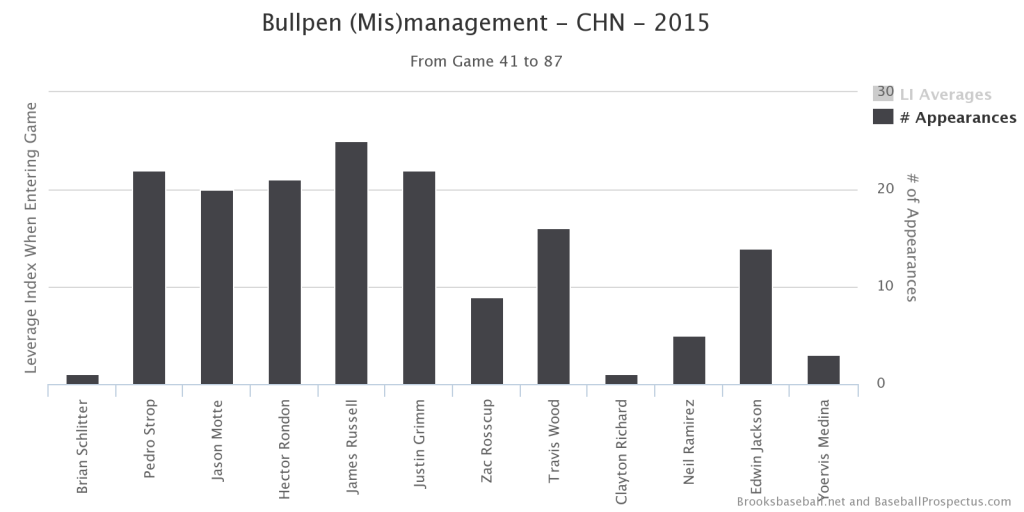

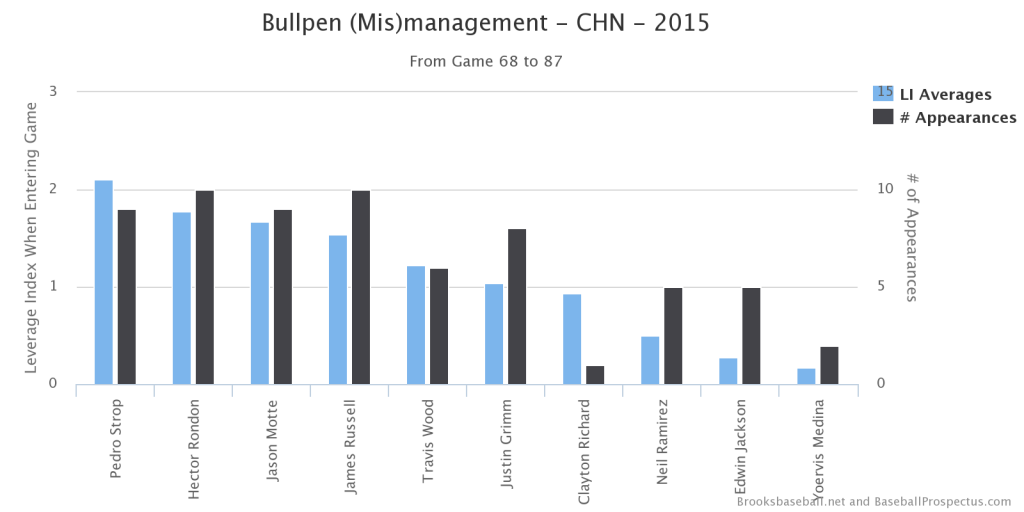

There are, as is typical of any bullpen over any given six-week stretch, five guys who clearly had full membership in the bullpen and carried Joe Maddon’s trust: Pedro Strop, Jason Motte, Hector Rondon, Zac Rosscup, and Phil Coke. Now here’s the same chart for the next 47 games, bringing us up to the All-Star break:

Of that core of five arms, only Strop, Motte, and Rondon remain. James Russell and Justin Grimm have taken the places of Rosscup (ineffective, then injured) and Coke (ineffective, thus released). The secondary left-hander role has shifted onto Travis Wood, after he was demoted from the starting rotation.

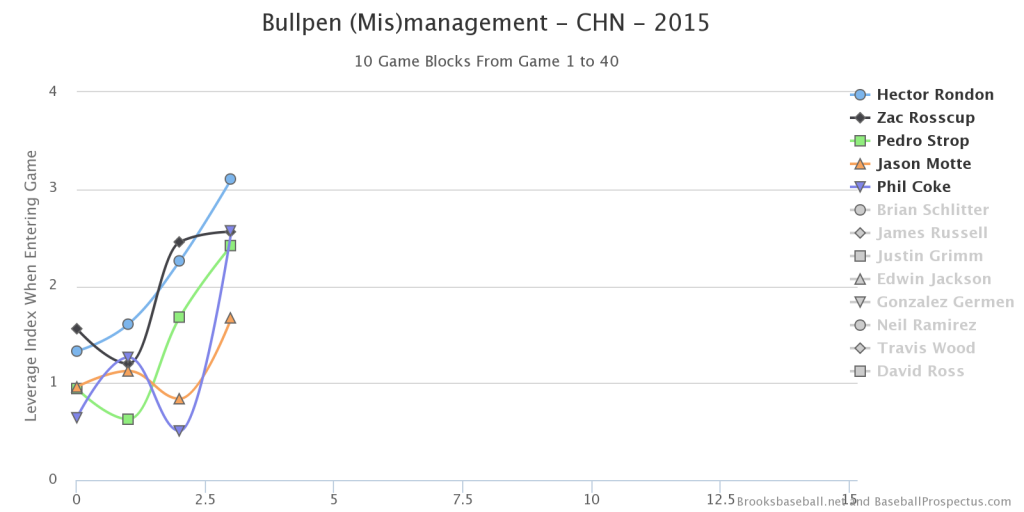

Nor is it only the makeup of the bullpen that has changed. Roles and places within the hierarchy have shifted, too. Here are the average Leverage Indices (upon entering the game; not across all batters faced) for the relievers who bore significant workloads during the first 40 games, broken down into 10-game blocks of time, to show changes. (Leverage Index (LI) is a measure of the sensitivity of a game’s outcome to the outcome of any given plate appearance. A higher LI means a pitcher pitched in more important situations, on average. A 1.00 LI is exactly average; late-game, one-run margins often involve LIs north of 1.50 or even 2.00.)

Don’t pay inordinate attention to any given block’s variation from another. A guy might see much higher-leverage situations over a two-week span than over another simply because the team played a lot of close games during that stretch, or because another pitcher or two was unavailable (although, of course, it could also be a merit-based change). Focus mostly on the relationship of each pitcher’s average LI to those of the others over each span. The takeaway: Rondon was the clear alpha dog of the bullpen. Maddon trusted Motte more than Strop early on, but Strop much more after the first few weeks. Zac Rosscup earned his way into Maddon’s heart, and was a full-fledged set-up man by the season’s first quarter post.

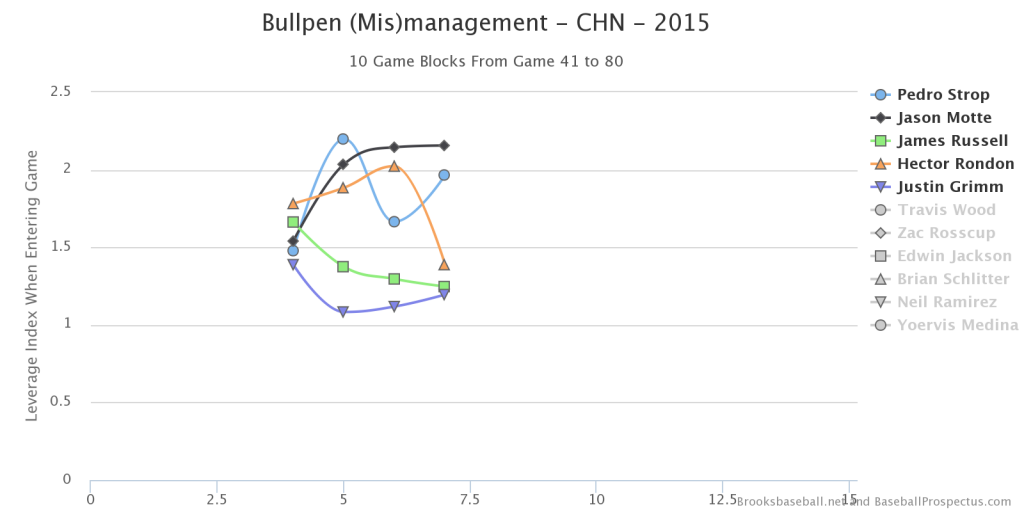

Here are the LIs for the five guys who have shouldered the heaviest load in the next 40 games (the fifth data point for each player was loopy and uninformative, if I went out to 87 games, so I trimmed it off):

Motte has taken over as the closer and the high-leverage stopper. Rondon remained a trusted co-ace for a while, but a few weeks ago, Maddon downshifted his former closer into more of a middle-relief role. Strop, whose streaks of heavy usage tended to end with pairs of disastrous appearances, has been handled with kid gloves when he has shown wear; that shines through here. Notably, Russell and Grimm are high-volume throwers, but Maddon does not yet trust either (especially Grimm) with much of anything important.

Last unwieldy chart, I promise. Here are the number of appearances and average LIs of each Cubs reliever over the last 30 games:

This might be the best snapshot of the team at this moment. Strop, Rondon, Motte, and Russell are the core four arms (Russell still doesn’t carry much of Maddon’s faith, but it’s clear Maddon prefers him when he needs to get an important lefty out, and Wood more as a long man). Wood and Grimm are chewing up innings, but neither is seeing much in the way of high-leverage work. Neil Ramirez and Edwin Jackson are mop-up men, the former because he hasn’t yet shown that he’s fully recovered from the shoulder inflammation that stalled his season, the latter because the Cubs don’t want him around, but won’t pay him to go away. Clayton Richard and Yoervis Medina (plus Brian Schlitter, not pictured) are the fungible guys the team could take or leave, at the moment.

It’s worth going over all of this, because it gives us an idea of how the second half might shape up. Strop’s inconsistency has caused the organization genuine concern, as evidenced by their willingness to move him out of critical situations when he’s been used too heavily. Rondon and Motte are both trusted back-end guys, but neither Maddon nor the front office have made any gesture that indicates they will rely on them. (Good thing, since both have had Tommy John surgery before, and neither has the full skill set of an elite modern reliever.)

More importantly, though, what this shows is the potential for further turnover and improvement in the second half. The Chicago bullpen has been considerably better over the last two months:

Chicago Cubs Relief Pitchers, 2015

| Month | Batters Faced | K% | BB% | AVG | OBP | SLG |

| April | 265 | 24.2 | 6.8 | .229 | .284 | .359 |

| May | 354 | 21.2 | 11.9 | .253 | .348 | .423 |

| June | 367 | 22.3 | 9.0 | .199 | .276 | .284 |

| July | 134 | 26.9 | 9.7 | .222 | .301 | .342 |

While it might not be fair to expect them to continue at the levels of excellence to which they’ve risen since the beginning of June, it’s no more fair to dismiss the possibility. Five teams allowed sub-.500 opponent OPSes in relief during April. The .643 OPS the Cubs are allowing in July is good for just 10th in baseball this month (an admittedly small sample, for all teams). In the modern era, it’s far from impossible for many teams—particularly one with as much relief talent as the Cubs have—to hold opponents to a .300 or worse OBP once the reliever parade begins each game.

That said, as we’ve seen already, the players on hand at the moment are unlikely to be the ones who give the Cubs the best chance to do that from now through the end of the season. Grimm will have to keep firm enough hold on his command to take on a higher-leverage role and succeed. Motte and Rondon need not only to stay healthy, but to miss more bats. (To their credit, both men have had excellent control, which mitigates their unimpressive strikeout rates. Still, at a certain point, crack! kills.) Even if those things happen, the bullpen will probably need reinforcements, and the truth is, it’s unlikely that all of those things will happen.

That’s where Rafael Soriano comes in. He’s reportedly hitting the mid-90s with his fastball, and he has allowed only four baserunners in as many innings in the Southern League so far, striking out three. It’s also where Carl Edwards, Jr. comes in: He’s whiffed 59 of 172 opposing batters in Double- and Triple-A this season, though he’s also walked 30. Crucially, both Soriano and Edwards will be able to bring something to the table in August that someone (Motte, perhaps, or Ramirez) won’t: a fresh arm. Soriano waited until June to sign as a free agent, and Edwards, despite having thrown more innings than even Strop this year, has yet to pitch on fewer than two days’ rest. He’s often going multiple innings, as he attempts to remain semi-stretched out. Whether the Cubs would prefer to modify that role or simply wait until rosters expand in September to call him up, though, there’s no doubt Edwards can help the bullpen with his lightly-used, electric arsenal.

Beyond those two, there are the aforementioned Medina; Corey Black, a starting prospect until a couple months ago, who is still making the transition to an Edwards-like role in Double-A, but flashes impressively dominant stuff; and Armando Rivero, a hard-throwing Cuban emigre whose inconsistency has held back his own intermittent dominance. None of those five pitchers are left-handed, and none are without significant risk, but they all have major upside, too. To that list, add Tsuyoshi Wada, who could be shifted into a relief role if the team trades for an upgrade to its rotation at the end of this month, although he might be a bit redundant, with Wood already in place.

The Cubs’ second-half bullpen might look very little like the one from the first half: more Ramirez and Grimm, less Strop and Rondon, (hopefully, at some point) no Edwin Jackson, and a big infusion of depth and fill-in work from the likes of Soriano, Edwards, Medina, Black, and Rivero. If Maddon continues his masterful management of the group, though, it need not be any less successful a unit.

Lead photo courtesy of Tommy Gilligan-USA TODAY Sports