Photo courtesy of Matt Marton-USA TODAY Sports

Through Monday, Javier Baez was batting .311/.388/.522 in his first 103 plate appearances of the season at Triple-A Iowa. Despite dealing with the tragic loss of his younger sister at the beginning of the season, and taking time away from the team to share in his family’s grief, Baez appears to have absorbed (and made solid, critical strides toward implementing) the changes in approach and swing mechanics that became obviously necessary during his difficult rookie season.

He’s been so successful, and the parent club’s start has been so encouraging, that the long-simmering conversation about what the Cubs would do to resolve their apparent logjam in the middle infield has all but boiled over. It’s the most talked-about long-term concern in Cubdom, not only because it involves perhaps the three players who have received the most attention from Cubs fans over the last year (Addison Russell), three years (Baez), and five years (Starlin Castro), but because it promises rather grandiose resolution. It’s presumed, and perhaps inevitable, that this glut will eventually be solved by a trade—that one of these very. very talented young players will be dealt away to help address the team’s weaknesses. The fact that that now feels imminent makes the whole thing very salacious.

I don’t subscribe to the idea that a trade is the right way to alleviate the saturation of these two positions, though. I don’t even believe this is the time for Chicago’s front office to attempt to separate wheat from chaff. Baez does belong on the Chicago Cubs. So do Castro and Russell. I propose promoting Baez, and making a three-man middle-infield rotation out of the three players.

This will be called radical, by many. I know, because I’ve tossed it out on Twitter more than once, and have gotten something just shy of a raised-eyebrow emoji in return. (Does such a thing exist?) But hear me out.

First of all, we should establish something: the Cubs are a good, competitive team. That’s critical to any argument in favor of this move. We should talk about the developmental implications of it, and we will, but first and foremost, the middle infield à trois is a strategic maneuver aimed at maximizing wins at the big-league level this season. Baez, Castro, and Russell are three gifted players, each with multidimensional games, but they all have serious, sometimes costly flaws. If they didn’t, we wouldn’t be having this conversation, because the advisable thing to do would be to trade the one with the glaring weakness (or weaknesses). As it is, no two of them make up anything akin to an elite big-league double-play combination. The three of them, though, might form the second- or third-best unit in baseball. It just needs to be a properly constructed system.

Here are the platoon-split statistics for each of the three players since the start of 2014, covering all levels. Obviously, we’re not comparing apples to apples here, and even more obviously, the samples are small enough as to discourage the wise reader from taking the numbers too seriously. Still, it’s important information.

Starlin Castro Batting Splits, 2014-15

| Split | PA | AVG | OBP | SLG |

| RHP | 603 | .277 | .318 | .410 |

| LHP | 152 | .324 | .375 | .432 |

Javier Baez Batting Splits, 2014-15

| Split | PA | AVG | OBP | SLG |

| RHP | 551 | .253 | .323 | .459 |

| LHP | 211 | .207 | .256 | .451 |

Addison Russell Batting Splits, 2014-15

| Split | PA | AVG | OBP | SLG |

| RHP | 350 | .263 | .317 | .427 |

| LHP | 92 | .356 | .391 | .667 |

Baez is, by no small margin, the best hitter in the bunch against same-handed pitchers. That’s somewhat surprising, and given the way it breaks down, I’ll understand some skepticism about it: Baez hit only .177/.229/.317 in 175 plate appearances against righties in the Majors last year. I (tentatively) buy it, though. Power is the easiest offensive skill to hang onto without the platoon advantage, and it’s by far a bigger part of Baez’s game than of Castro’s or Russell’s. It’s also somewhat easy, when watching Castro or Russell hit against good right-handers, to see the problems they have with them.

Okay, so in many cases, Baez should start against righties, and sit against lefties, whom Castro and Russell have handled so well. Since all three are right-handed batters and the samples are small, though, a straight platoon is neither likely nor optimal. There are other ways to break them down, to discover the matchups that might favor each.

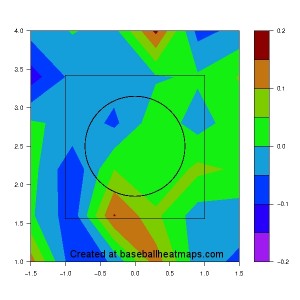

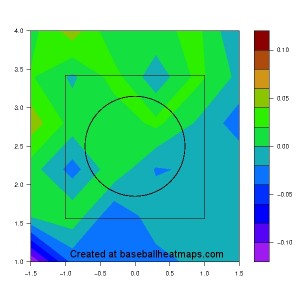

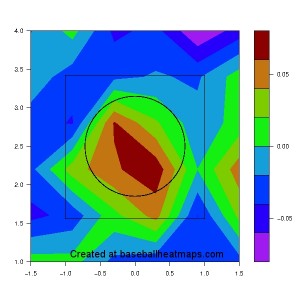

Thanks to baseballheatmaps.com, we can estimate the way each handles pitches in various parts of the strike zone. These charts reflect not only the impact of at-bat-ending outcomes (hits or outs), but all outcomes: pitches taken for balls (or strikes), swings and misses, foul balls, everything. The scales are relative to the league average for that area.

Castro:

Baez:

Russell:

Exceptional at going down to get the ball, and at stinging pitches on the outer part of the plate to all fields; big holes inside, especially low and in.

In the cases of Russell and Baez, I’m inclined to maintain skepticism about the predictive value of these maps. Baez was clearly not the player the Cubs hope he will eventually be last year, and might already be a very different one than he was then. Russell has struck out a ton and been a mess against breaking pitches (he’s whiffing on over 52 percent of his swings at them, in no small part because he’s chasing them far outside the strike zone), which doesn’t really fit his scouting report. Still, in one reading of the data, we have another way to prioritize playing time: Castro against pitchers who elevate, Russell against sinker specialists, Baez for the strike-throwers.

You can see how this decision can be made a hundred different ways, every day, even if the differences are sometimes vanishingly small. Castro is the best handler of offspeed stuff in the trio. Russell is best at combating fastballs. Baez is the best and fastest baserunner among them. I leave it to the judgment of the Cubs themselves who plays each of the positions in question best, but certainly, absent some other clear determinant, the starting tandem behind a ground-ball guy like Jake Arrieta could simply be whichever offers the best defense.

Now, let’s talk about the developmental logistics of this, and how it can be done without derailing the growth of all three players (to whatever extent Castro, especially, has growing left to do). To me, it’s much simpler than people are making it: each player just needs to start a roughly even share of the time. That shouldn’t be a problem. There’s no clear-cut best or worst in the bunch, right now. They’re different mostly in the shape of the value they deliver, rather than the amount thereof. Therefore, they can spread the playing time evenly without hurting the club.

There’s already a team in the Cubs’ division doing this. Jung-Ho Kang has started 12 games at shortstop for the Pirates, and 10 at third base. Josh Harrison has started at both second and third. Nor would it be new to Joe Maddon, who used Ben Zobrist extensively on both sides of second base each of the last three seasons, and Sean Rodriguez the same way the year before that, and Reid Brignac the same way the year before that. Castro would probably start almost exclusively at shortstop (perhaps sliding to third, on occasion, with Kris Bryant seeing a bit more time in left field against lefty starters), but the others would see time at each spot. If that meaningfully took either off track, it would be more a failure of makeup on their part than a failure of player development on the Cubs’.

Only one issue really demands careful consideration, and that’s the encroachment upon full playing time for all three guys. As it stands, Russell is the everyday second baseman in Chicago, Castro is the everyday shortstop, and Baez is an everyday utility man for Iowa. They would all lose playing time under my proposed system, going from seven starts a week to four or five. They would lose a few opportunities to work on the things they do worst, and most dauntingly, if the situation were mishandled, they might all try much too hard to win their playing time by force. All three have been guilty of trying to pull everything, selling out for power, and racking up either strikeouts or weak grounders to shortstop, and that’s without the pressure of diminished playing time nagging them.

For what it’s worth, the refrain that young players need reps, that only playing constantly permits one to find and correct holes in one’s game, is one nearly everyone who changes clothes at the ballpark each day sings in unison. I don’t buy a scrap of it. I think time off, so long as it’s a day or two and not a week or two, is a good thing for a developing hitter. I think the need to play every day in order to find success is the mark of a player without the tools of focus, preparation, and mental sharpness necessary to become a good big-leaguer. Good players use a day off to freshen their body, educate themselves about upcoming opponents, consolidate and concretize the good things that happened the day before, and forget about the bad things. There’s no reason a 21-year-old like Russell should struggle to do those things, under positive guidance from the coaching staff. Still, I feel a need to mention it, because there is some risk that one or more of these guys will adjust badly to a change in schedule.

It’s a risk the Cubs need to take. Maybe, after reviewing the upcoming schedule (pitching matchups, venue, etc.), Cubs coaches could give them all a schedule at the beginning of each week, to reinforce the idea that playing time will be distributed evenly and methodically, not based on a hot hand. Maybe Maddon’s experience with similarly convoluted timeshares would come in handy, and he could manage the personalities of each player well enough to make it a non-issue. In any case, the Castro-Russell pairing is actually producing below-average value up the middle. Baez would help cover some of the holes in their play, not only by sliding into their place when they face bad matchups, but by keeping them fresher as the season wears on.

The Cubs were supposed to be an unusually deep team, able to rest more starters than most and stand up to the grind well. Thanks to early-season injuries (Tommy La Stella, Mike Olt) and cratering performance (Arismendy Alcantara), things haven’t panned out that way. Promoting Baez, but keeping Kris Bryant and Chris Coghlan generally in their places, would help restore the vision the front office had for this team in March.

I like the thinking here. And I’ll second that some time off can be a good developmental tool. Watching a big-league game from the dugout allows players to notice things they miss while on the field that they can take into the field next time out. This probably won’t happen, but I applaud the forward thinking.

This is really great stuff, Matt. Seems to me that this would be a unique and ultimately valuable solution to the problem we currently face up the middle. I’m not sure the Cubs will do this, but I wouldn’t rule it out either. I do, however, think this is probably the ideal scenario for managing the three players, at least as they currently are.

“I think the need to play every day in order to find success is the mark of a player without the tools of focus, preparation, and mental sharpness necessary to become a good big-leaguer.”

Bold statement.

” it involves perhaps the three players who have received the most attention from Cubs fans over the last year (Addison Russell)….”

You do realize that you’re saying that Addison Russell has received more attention over the past year than Kris Bryant, right?

As for your ideas themselves here, I think I’m a fan.

Oh, hi Dave. Fancy seeing you over here. I assume I can look forward to some excellent grammatical critique of my articles?

The statement about time off is poor. From experience, its more akin to waiting for a text back from a girl than taking extra time to prepare for an exam. The mind wanders and OVERanalyzes. Its too difficult at a young age to have control over something like that. Time off is good, but do it with player psychology in mind more than anything else.