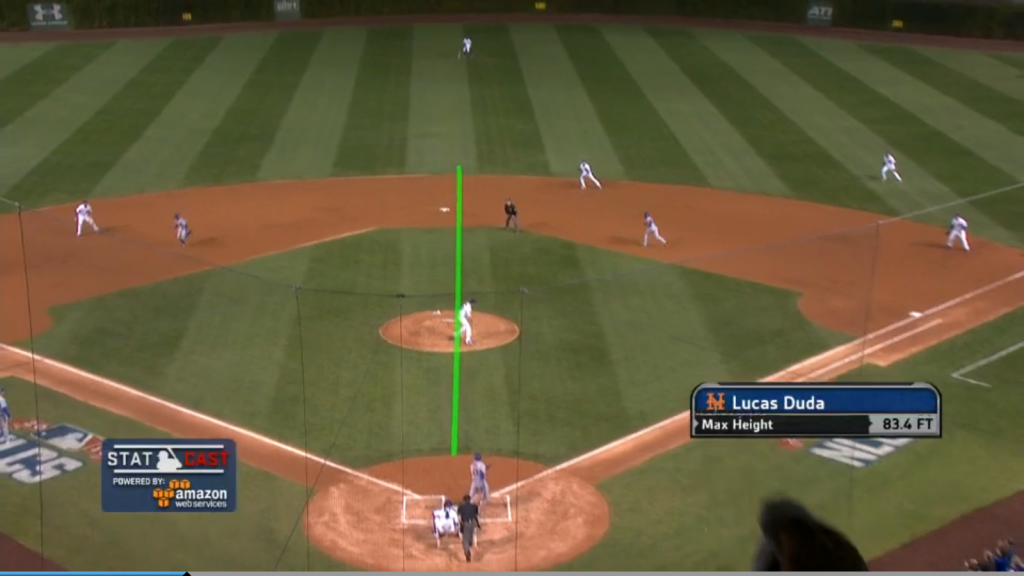

In the fourth game of the 2015 National League Championship Series, down 3-0 in the series, the Cubs had their backs against the wall. And in the top of the first inning, Lucas Duda set the tenor of the game when he drilled a three-run shot into center field on a full count offering from starter Jason Hammel. Like many other teams before them that season, the Cubs deployed an infield shift on Duda, positioning three infielders to the right of second base. Of course, it meant nothing in this situation, as the ball sailed over the ivy and into the bleachers.

After facing just two batters in the top of the second inning, Hammel’s night was done, and he was pulled from the game in favor of lefty Travis Wood. Duda again stepped into the box with two men on base, and again the Cubs put the shift on him. With a 3-2 count, Wood threw a fastball inside, hoping to force Duda to pull an easy grounder into the shifted fielders behind him. But it caught too much plate, and Duda was able to sneak a two-run double right past the Cubs defenders. In the end, the Cubs were no match for the surging Mets offense, and lost their final game of the season in lopsided fashion.

Commentators often point to individual situations like this as an indictment of the dangers of shift defense. They point to the unfamiliarity that players have in playing out of position as well as the risk in leaving half of the infield vulnerable to bunts, but more often than not, shifts will take away more hits than they allow. League-wide, shift usage has trended up significantly. In 2010, major league teams shifted 2,464 times. Last season, that number went up to 17,733 shifts. Clearly, teams are increasingly more willing to shift, but there are still great differences in how each team approaches different batters. For Duda in particular, the Cubs were following the standard protocol. In fact, Duda was the third-most shifted batter in baseball last season—hardly a surprise considering his profile as a slow, left-handed power hitter.

|

NL Central – Infield Shifts |

||

| Team |

2014 |

2015 |

| Pirates |

660 |

971 |

| Reds |

212 |

426 |

| Brewers |

576 |

382 |

| Cubs |

316 |

381 |

| Cardinals |

367 |

313 |

Though the Cubs had no trouble deciding how to play Duda, they still had reservations about fully committing to shifting. The table above has shift totals for the last two seasons in the NL Central, taken from The Bill James Handbook 2016. It is useful to compare divisional opponents in this case because each team is more likely to face the same batters. In 2014, the Pirates and Brewers shifted twice as much as the rest of the division. The following season, the Pirates had pulled ahead with over twice as many as any other team in the Central. The Cubs, while modestly increasing their shift usage, were still reluctant to dive in to the same extent as the Pirates. This, on the face of it, is somewhat surprising, considering their analytically savvy front office, combined with the hiring of new skipper Joe Maddon, who presided over one of baseball’s shiftiest defenses during his tenure in Tampa Bay. But then, maybe they found something in the data they didn’t like.

|

Batters Most Shifted by Pirates also Shifted by Cubs in 2015 |

||||

|

Pirates |

Cubs |

|||

| Player |

Shifts |

BIP |

Shifts |

BIP |

| Jay Bruce |

40 |

45 |

24 |

47 |

| Adam Lind |

36 |

39 |

17 |

47 |

| Joey Votto |

30 |

47 |

5 |

46 |

| Jason Heyward |

28 |

51 |

5 |

62 |

| Brandon Moss |

21 |

21 |

14 |

15 |

To further explore where those reservations might lie, we can look at the top five batters most often shifted against by the Pirates that the Cubs also shifted on last season, as shown in the table above. Predictably, they represent the rest of the Central—two Reds, two Cardinals, and a Brewer. However, on a similar amount of balls in play, the Cubs shifted the same batters much fewer times than the Pirates. Jay Bruce and Adam Lind saw a shift nearly every time they faced the Pirates. But with the Cubs, it was about half. With Joey Votto and Jason Heyward, the Pirates shifted aggressively, while the Cubs were much more timid, barely shifting them at all. The only batter of the group they seemed to agree on was Brandon Moss, who was shifted by both teams at about the same rate.

So, why the discrepancy? Maybe it was a case of familiarity. The Pirates have long advocated using the shift, committing to an organization-wide defensive strategy that would be taught at the lowest levels of the minors up to the major league level. This would not only allow infielders to adjust to the differences in playing out of position, but it would also let pitchers get mentally accustomed to the unorthodox defenses behind them—there’s no doubt that the hits that beat the shift are always remembered more clearly than the hits that are taken away. Or, it could have been a different perception on the type of batter that constitutes a good shift candidate. The batters here that were most shifted by the Cubs, Jay Bruce and Brandon Moss, also pulled their ground balls at a higher rate (71 and 67 percent, respectively) than the others.

|

Pirates & Cubs Shift Efficiency |

|||

| Team |

2014-15 Shifts |

2014-15 SRS |

2014-15 SRS per 100 shifts |

| Pirates |

1,631 |

14 |

0.86 |

| Cubs |

698 |

13 |

1.86 |

I believe it has more to do with the second possibility. Shift Runs Saved (SRS), a measure of team shift effectiveness, can be used to estimate this impact, charted in the table above. Over the last two seasons, the Cubs have shifted a total of 698 times, saving 13 runs. On the other hand, the Pirates have shifted 1,631 times, saving just 14 runs. It’s not difficult to see that the Cubs were much more efficient in their shifting in this time period, saving an extra run on every hundred shifts compared to the Pirates. Is this conclusive evidence that the Cubs are just better at shifting? Not necessarily, but the sheer disparity between each team’s shift efficiency is hard to ignore. Even park-adjusted defensive efficiency, which measures how many balls in play a team converts into outs, points to the Cubs as a much more sure-handed team than the Pirates in the last two seasons. While this isn’t definitive evidence, it seems likely that whatever internal models and metrics are used within the Cubs front office to optimize shift strategy have been more successful at targeting the right batters.

Looking forward to upcoming season, it will be particularly interesting to pay attention to how the Cubs continue to defend opposing batters. Their front office has shown a clear commitment to improving defense, whether it has been moving fielders to less demanding positions, as with Kyle Schwarber and Starlin Castro, or acquiring players with stellar defensive reputations, like Austin Jackson and Miguel Montero. The question that remains is how, if at all, will their shift strategy change? Prototypical shift candidates like Duda will continue to be hounded by the shift, but as league-wide shift usage trends upward in a significant way, will the Cubs follow suit?

Special thanks to Baseball Info Solutions for providing research assistance.

Lead photograph courtesy Aaron Doster—USA Today Sports.