She arrived at the Sphinx—the mythical beast posted on an outcropping, guarding the bridge to the World Series—anticipating the riddle of legend.

The Sphinx spoke. “What creatures walk on four balls in the regular season, but strike out on three pitches in the playoffs?”

—

The cold randomness of the playoffs was the only legitimate fear for Cubs fans coming into October. The team had no real weaknesses, having shored up its bullpen down the stretch, and its health was surprisingly good. Jake Arrieta being bad or Kyle Hendricks somehow turning into a pumpkin were maybe small fears (the latter, especially, not really having any merit), but any nervousness came not from the Cubs’ composition, but from the nature of the thing itself. What could torpedo this club was a few poorly timed skids from key players, a function of the shortness of the playoffs and the higher quality of pitchers.

With seven games played, including two consecutive shutouts at the hands of the Dodgers, that fear has solidified itself in the form of the Cubs’ top-of-the-order slump. Much has been made of the Cubs’ hitting woes in the first seven playoff games, most of it unwarranted considering the general dearth of hitting in the playoffs, but Anthony Rizzo’s poor performance has stood out in its futility. The first baseman has two hits in 30 plate appearances (one being his broken-bat infield single on Tuesday), with seven strikeouts and four walks, one run scored and no RBI. It makes for an ugly line, with lots of zeroes and ones. Rizzo’s impotence, in conjunction with that of Ben Zobrist and Addison Russell, has hung Kris Bryant and his solid postseason efforts out to dry, driving him in only once (a Zobrist double in Game Four of the NLDS).

By my unscientific count, Rizzo has flied out three times, grounded out six, popped out twice, and lined out five times. It’s the last number that’s encouraging, as Rizzo has clearly squared up some balls in these two series. In fact, it appears as though he’s improved: although he’s faced very stiff opponents in the form of Clayton Kershaw, Rich Hill, and Kenley Jansen, he’s managed a pair of walks, a pair of loud lineouts, and some very deep at bats versus the Dodgers.

The slugging first baseman’s struggles might at first appear to be a function of facing left-handed pitchers in 17 of his 30 playoff plate appearances, but he’s fared as well against the southpaws as he has against the righties. In fact, his two worst games were the first two in the NLDS, versus righties Johnny Cueto and Jeff Samardzija, in which he looked most uncomfortable at the plate and reached base zero times. So, while Rizzo hasn’t hit either righties or lefties well, it’s not the handedness of his opponents that is giving him fits at the plate.

Rizzo’s patience hasn’t suffered from playoff pressure, either. He’s seen 126 pitches in 30 plate appearances, good for just a tick over four per PA, and his season average was just a hair under four. When we turn to the types of pitches he’s seen, however, we begin to get a sense of why he may have struggled so far.

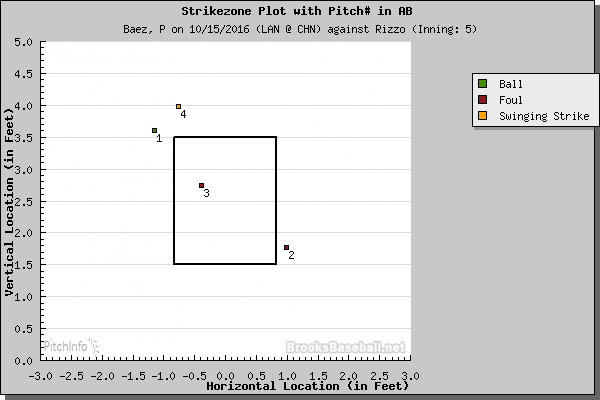

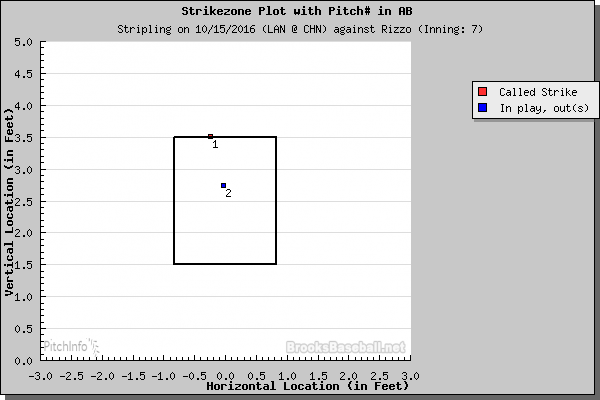

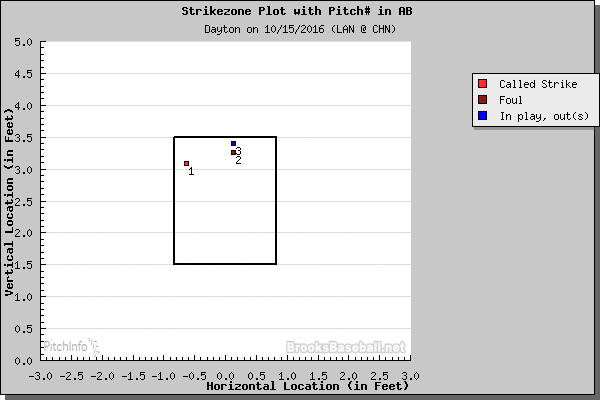

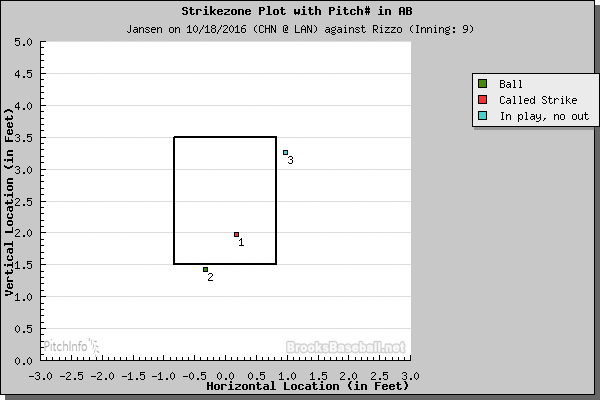

Rich Hill’s two-pitch repertoire has an outsized weight on the types of pitches Rizzo has seen this postseason versus lefties, with the percentage of curveballs Rizzo has seen from lefties between two and three times greater than that which he saw in the regular season. But versus righties, there’s a possible plan of attack: twice as many cutters, no curves. We’ve seen Rizzo get jammed a few times this postseason already, and righties’ reliance on cutters points to why. Samardzija and Cueto both pounded Rizzo in on the hands in the Giants series, while Dodgers righty Kenta Maeda, and lefties Kershaw and Hill stuck to their usual effective gameplans. Dodgers’ relievers, however, opted to throw Rizzo up-and-in: these three plots from at-bats versus lefty Grant Dayton and righties Ross Stripling and Kenley Jansen, respectively, illustrate that approach.

Baez struck out Rizzo with a high fastball, Stripling got a flyout, Dayton induced a high popup to left, and Jansen shattered Rizzo’s bat. The Dodgers’ generally hard-throwing relievers have succeeded in executing their plan to pitch Rizzo up in the zone, and above the zone, to get popups, jammed grounders, and strikeouts. These at-bats (of which there are admittedly few) suggest that the plan for right-handed pitchers is to start the hitter away, and move in with hard stuff (including cutters, a left-hander’s nightmare) to induce weak contact or a whiff. Surely Rizzo is aware of this, and it’s not a new strategy, but it’s been fairly effective so far in a small dose.

With young lefty Julio Urias on the mound on Game Four, Rizzo has a chance to pounce on fastballs and sliders that, while good, are not Kershaw-quality. The threat of being jammed up-and-in is lower, and it falls on Urias to execute those pitches if he deviates from his heavy low-and-away profile.Of course, that’s moot if Dodgers manager Dave Roberts goes to his bullpen early, as many anticipate given Urias’s inexperience. Rizzo isn’t mired in the same “can’t hit his butt with both hands” slump that Addison Russell appears to be in, given Rizzo’s instances of hard contact and long at-bats, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he were to show up big in these pivotal games in Los Angeles.

Lead photo courtesy Jon Durr—USA Today Sports.