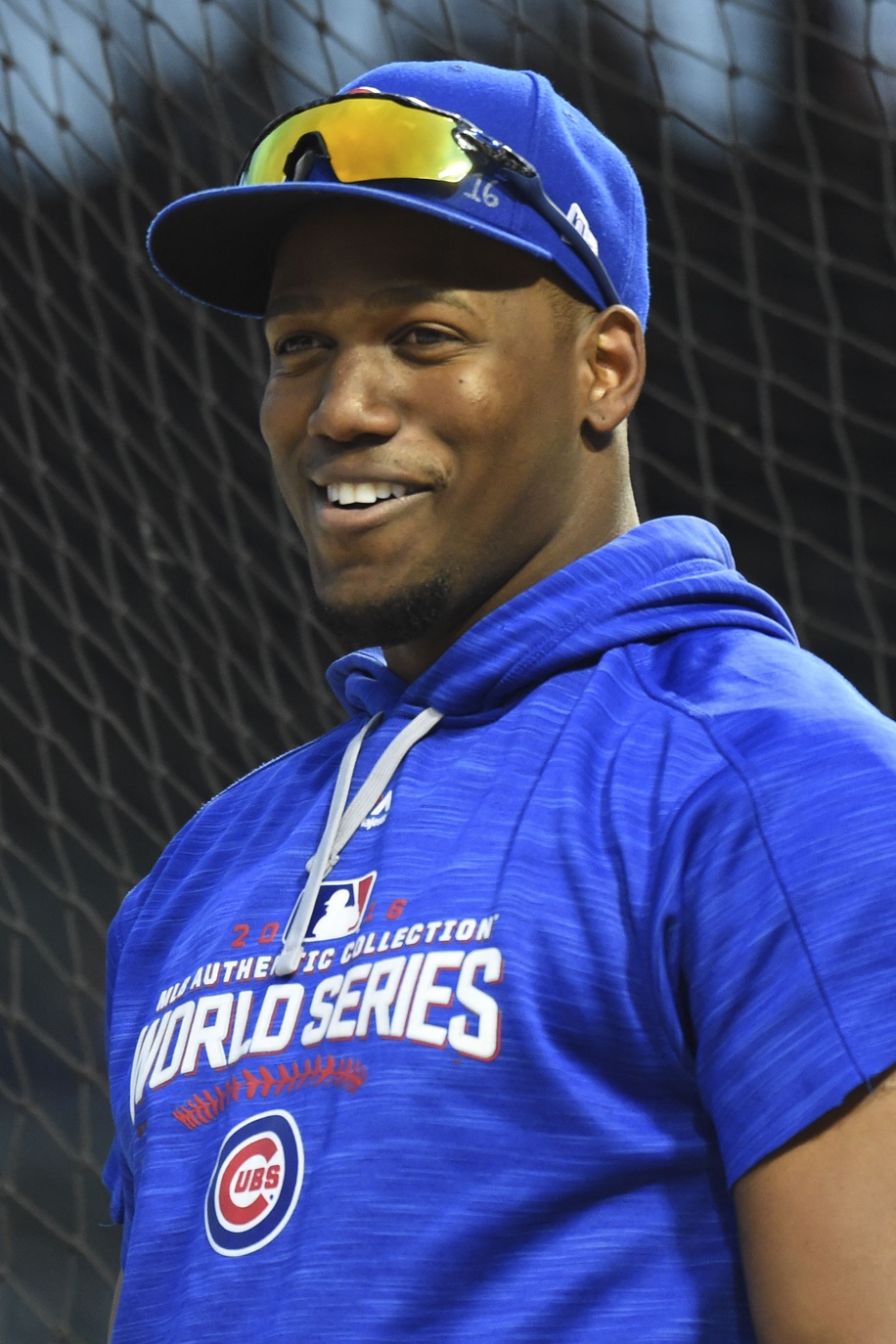

The Cubs’ World Series championship would not have been possible without the contributions of several international free agent signings. Six of the 25 players on the World Series roster arrived in American professional baseball as international free agents, and two of them (Willson Contreras and Jorge Soler) initially signed with the Cubs. While Contreras made the major-league minimum salary (just over $500,000) in 2016, his rookie year, Soler banked a few million dollars in the fifth year of his nine-year, $30 million contract he signed in 2012. The rest of the Cubs’ former international free agent players—Aroldis Chapman, Pedro Strop, Hector Rondon, and Miguel Montero—made between four and 14 million dollars.

All of this is to say that players from outside the United States, Puerto Rico, and Canada impacted the team that we watched all season, and the team that captured the first Cubs World Series in over a century.

Of course, many of you know this. What might be new to you, however, is the precarious state in which prospective MLB players from “international” countries find themselves this offseason, and how it might impact baseball’s labor-management dynamics. The current collective bargaining agreement (CBA) is up on December 1, and those who are at the table negotiating—representatives of the union and the owners—could radically change the path that international players take to the majors.

Reports indicate that MLB (here, meaning the commissioner’s office and the owners) desire an international draft, as they have for years, beginning with 10 rounds in March 2018. A complementary raise in the signing age, from 16-years-old to 18-years-old, would bring international players under the same age stipulations that govern their counterparts who are already subject to the draft. MLB would control facilities in the Dominican Republic responsible for educating and developing Latin American players, giving them a far larger role in the development process than they have now; the current system is that of decentralization and devolved responsibilities. Development is incumbent on scouts and trainers (buscones, colloquially), and MLB has no real influence before a player turns 16 and is eligible to sign and join team training facilities.

Contrast that proposal with the current system, arrived at during the bargaining over the current labor agreement. For the past four seasons, MLB has capped the amount that each club could spend on international free agents, contingent on their major-league results in the previous season. Going over the allotted amount would incur a team heavy fines, and bar them from signing free agents for above certain bonus amounts for the following signing period. Clubs could trade international bonus pool “wedges” (i.e. chunks of allotted cash) similar to how other leagues trade draft picks. The system resulted in many teams’ exploitation of what they saw as relatively soft penalties, with clubs rich and “impoverished” alike blowing past spending limits in pursuit of the best international talent.

Under this system, the Cubs famously signed both Gleyber Torres and Eloy Jimenez, topping their allotted spending, paying the 100-percent overage penalty, and all but sitting out the next signing period’s frenzy. Those two players’ success—both now look like true future MLB stars—demonstrate why teams were willing to shrug off MLB’s penalties. Likewise, the system still benefitted the players significantly more than the draft system benefitted drafted players: the Cubs signed 20 players to contracts with bonuses over $100,000 in 2016, whereas only players drafted in the first 10 rounds of the Rule 4 draft come with recommended slot values over that amount, discouraging teams who would give out large bonuses to players drafted in the later rounds. On the other hand, teams are confused as to why mid-first round draft slots sometimes carry larger values than entire international signing pools. It’s a paradoxical system that produces bizarre results. The smaller the pool, the bigger the incentive to exceed your pool in an effort to accrue the most talent possible.

For two years now, Commissioner Rob Manfred has expressed displeasure with how teams have flouted those spending limits, although it remains unclear how the current system, which does not seem to have deterred smaller market teams like the Rays or Athletics, appreciably disadvantages certain teams. The truth is that most teams can afford to sign the best international players nearly every offseason, if they choose to do so. MLB’s complementary overtures citing human rights abuses and corruption amongst buscones merely obfuscate the owners’ true desires: salary suppression. Some players are exploited by their trainers, and the dubiously ethical circumstances of Yasiel Puig’s path to the majors remain fresh in many minds, but, according to those closest to Latin American amateurs, many more players form mutually beneficial relationships with their trainers that help them develop fully and sign with teams. Ultimately, it comes down to the owners’ iron will to defend their pocketbooks.

The MLBPA, for their part, has been fairly staunch in their opposition to an international draft, despite their general willingness to sell out players who are not union members (those who are not on 40-man rosters) in order to garner larger gains for union members. CBA negotiations have reportedly transpired smoothly, aside from strife over the draft, and the Players’ Association might make a stand solely because an international draft is a bargaining chip several times larger than any demand they players have made, besides the failed prospect of a 154-game season.

Opposition from Latin American players and their support networks has been vociferous. Not only do they players, their families, and the trainers stand to lose money, but they will relinquish nearly all autonomy in player development. Scouts, too, have expressed displeasure, citing a fear of MLB’s lack of developmental infrastructure in the region, and even some baseball operations executives have voiced concern, most notably new Twins GM Thad Levine. Players and trainers organized to boycott amateur showcases hosted by MLB in both the Dominican Republic and Panama (the latter moved from Venezuela due to ongoing safety concerns), and MLB subsequently canceled the events. The solidarity was quite remarkable, and many turned out in actual protest of the events in the Dominican Republic. Latin American players naturally value their relatively self-determined paths to the majors, and they will be loath to relinquish that control.

The final component of the proposed system changes, the change in signing age limits, is the most concrete factor that the MLBPA can latch onto as a reason to oppose the draft. While formerly drafted players in the union sometimes chafe at the larger contracts that international amateurs sign, the fact that they sign at age-16 instead of 18 or later is a boon to the union: the earlier the free agent contract, the sooner the player reaches MLB, and the sooner that player is eligible for a larger free agent contract. A Latin American star who signs his first professional contract at 16, like Xander Bogaerts, Nomar Mazara, or Julio Urias, can debut at a young age, setting himself up for a big payday in his mid-20s. Rare is the drafted major leaguer like Jason Heyward, who received his first free agent contract at 26. Union resistance to an international draft makes international players more money as major leaguers and brings them into union membership earlier.

There are alternatives to the current system that do not constitute the radical, regressive implementation of an international draft and do not carry with it. Ben Badler of Baseball America, who has dutifully reported on showcase boycotts and the particulars of the draft, outlines a few in this piece. With the December 1 deadline to agree on a new CBA imminent, the resolution of the international draft question is imperative. In 2014, the owners shelved the draft due to union opposition; this year, they have steeled themselves much like the pharaoh in the face of Moses’s pleas. If the owners choose to die on the hill of the draft, then they risk a lockout for the first time since the disastrous 1994 player strike.

What’s certain is that contracts like Jorge Soler’s 9-year, $30 million one are not to be seen again for international players. The conditions under which the Cubs’ Latin American stars entered American professional baseball are gone, and future stars will receive less money and have both less clout in negotiations and less autonomy in their development as amateurs. A draft deprives players, families, team employees, and fans of a system that pays players more fairly, relies on experience and cultivated relationships, and maximizes the health of organized baseball and its dependent networks in Latin America. It serves only the owners.

Lead photo courtesy Tommy Gilligan—USA Today Sports

one other neglected point is that the lack of a foreign draft is unfair to American players who can’t participate in the immediate riches under their contracts. Why should Kris Bryant make 1/10th what Puig does just because he was born in America?

The lack of a draft also penalizes teams that haven’t (or can’t afford) to develop a Latin American system. It also leaves the individual educational development up to the teams – incentivizing young players to leave their education behind. (Some like the Yankees and Cubs have dramatically changed their education systems in recent years making their latin american facilities mini-colleges – but it’s not uniform).

As a free market conservative with libertarian tendencies – you’d think I’d love the current system – especially since it has enormously benefited the Cubs. But since it doesn’t offer American players the same opportunities to cash in early I will embrace consistency in saying the entire MLBP agreement could/should be revisited to allow all players the right to let the market gauge their value (but of course it won’t.)

Yes the Cubs bought a title. So let’s make it so only the big market teams can win.