“I saw a wounded baseball fan tottering down the street

Encased in bandages and tape, and bruised from head to feet

And as I called the ambulance, I heard the poor guy say:

‘I bought a seat in Wrigley Field, but it was Ladies’ Day’”

-Chicago Newspaper, 1929

I’m going to let you in on a little secret: I’ve been a Red Sox fan for 24 years and a Cubs fan for two. It was not until the Cubs signed and traded for and hired everybody who had ever passed through Boston that I began really paying attention to the team. But as soon as word got out that I was watching Cubs games at all, I was bombarded with .gifs and video and anecdotes forcing me to invest more of my time in the team. The source of these persuasions? My female-friend Cubs fans. I was struck by their fierce devotion to the Cubs, not yet knowing they are simply a small part of female Cubs fandom that dates back 100 years.

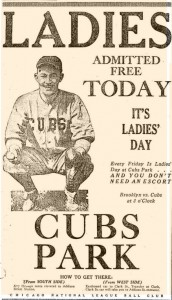

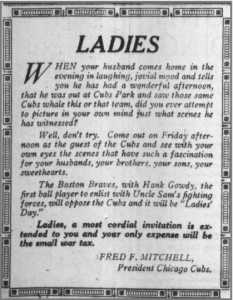

On June 4th, 1919, Congress passed the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote. Six days later, Illinois became the first state to ratify the 19th Amendment, 51 years after the state’s first consolidated suffragette movement. Eight months later, Chicago founded the League of Women Voters, a national effort to support the new amendment. Recognizing the significance of women even earlier than Illinois’s state government, however, were Wrigley Jr. and Cubs President Bill Veeck Sr. On June 6th, the club held its first Ladies’ Day, a promotion offering women aged 14+ free admission to Friday home games. During the lead-up to the vote on the 19th amendment, Chicago women attended games en masse, using the sport to demonstrate the full nature of their equality. Although the newspaper ad for the first Ladies’ Day did not fully recognize this independence, stating, “come out on Friday afternoon as guest of the Cubs and see with your own eyes the scenes that have such a fascination for your husbands, your brothers, your sons, your sweethearts,” it nonetheless drew a large crowd.1

The premise of Ladies’ Day dates back to at least the early 1880s, when various clubs held them sporadically throughout the seasons, but while they increased attendance by a couple thousand, they did not reach nearly the same popularity as they did for the Cubs. For much of its early history, baseball was viewed as a sport belonging to the hard-nosed working class, a sport wholly unfit for women. This notion, in part, held firm with the NL as Ladies’ Days for years were banned.2 However, sensing a money-making opportunity, Wrigley Jr. and Veeck spread word of Ladies’ Day via innovative radio and newspaper ads.

Reflecting on his decision to hold Ladies’ Days, Wrigley Jr. had this to say: “I held that no normal human being could remain indifferent to the allurements of baseball after being fully exposed to them…the theory of handing out a lot of free admissions to ladies was that women are the best advertisers in the world for anything they like.” Although Ladies’ Day began primarily as an advertising scheme for the Cubs and the newly built ballpark, its success could not have been predicted. Recounts Wrigley Jr., “a bargain-day rush at a big State Street store is a tame event alongside a Ladies’ Day at Wrigley Field.”3 Indeed, in 1919, the women attendees outdrew several teams’ total season attendance, and the promotion paid for itself via women who paid extra to get reserved seats and came back on other days.4

“In a thousand minor ways the world seems to be getting used to us…[but] in the religious world, the balance seems definitely on the wrong side”

-Nancy M Schoonmaker, “Women’s Progress in 1924”

As the 1920s progressed and women further embraced their rights, many religious institutions sought to prevent them from achieving equality. Chicago women increasingly took their r eligion into their own hands, opting to pray on Fridays rather than Sundays and at Wrigley Field rather than cathedrals. Throughout the 1920s, and 30s, Ladies’ Day brought approximately 2.5 million women to the ballpark on Fridays and many more as paying customers the other six days. Although attendance faltered in the early days of 1924 as the team hung around the .500 mark, Veeck and Wrigley Jr. helped increase it by appealing, once again, to Ladies’ Day. This time, however, the pair marketed the games to women as individuals rather than as male attachments, assuring women they did not need an escort to attend games. Sensing the opportunity to expand Cubs fandom, Wrigley Jr. began airing all games on radio in 1925 so that women could listen to them at home or during breaks at work and learn about the game before attending it. By the end of the decade, Ladies’ Day attendance was so high, the club created standing room sections along the field.5

eligion into their own hands, opting to pray on Fridays rather than Sundays and at Wrigley Field rather than cathedrals. Throughout the 1920s, and 30s, Ladies’ Day brought approximately 2.5 million women to the ballpark on Fridays and many more as paying customers the other six days. Although attendance faltered in the early days of 1924 as the team hung around the .500 mark, Veeck and Wrigley Jr. helped increase it by appealing, once again, to Ladies’ Day. This time, however, the pair marketed the games to women as individuals rather than as male attachments, assuring women they did not need an escort to attend games. Sensing the opportunity to expand Cubs fandom, Wrigley Jr. began airing all games on radio in 1925 so that women could listen to them at home or during breaks at work and learn about the game before attending it. By the end of the decade, Ladies’ Day attendance was so high, the club created standing room sections along the field.5

1924 and marked one of Chicago’s first serious forays into black rights, as black women participated in several UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association) rallies, parades, and demonstrations.6 However, black women seldom attended baseball games, particularly as Wrigley Field was located in an affluent white area of Chicago.7 While it is likely some black women attended games during the ’20s, their story fell to the wayside until baseball’s integration.

Ladies’ Day peaked during the 1929 season, drawing in over 200,000 women. Toward the end of the season, women unsuccessfully petitioned the Cubs to move potential pennant games to Soldier Field so that double the number of fans could attend. Further, Veeck decided to restrict tickets to 17,000 and create a weekly application system in order to ensure other fans got to see Friday games, too. Every opposing team left in awe of the passionate crowds, and on August 7, 1929, the Brooklyn Eagle wrote, “Women take naturally to baseball. They become fans quickly. In many cases the men of the family, who may not have been greatly interested in the game, become redhot fans because their wives or sisters are. And the women who get in free each Friday afternoon will pay for their tickets on other days once or twice a week. The only conceivable bad features is the fact that ladies’ days might get out of control.” Soon after, Ladies’ Day became routine for many other clubs, from the Dodgers to the Browns, and women became a necessity for baseball.8

“This is the age of women in sport and the women of Chicago have become real baseball fans.”

-Bill Veeck, Dixon Evening Telegraph, August 2, 1930.

A Ladies Day Crowd in 1932

During the Great Depression, women around the country were relegated to household positions while their male relatives found whatever jobs were available, often for fractions of the salary they should have been paid. But this did not prevent women from supporting their team. Newspapers remarked about the loyalty women had to the Cubs, as even the Great Depression could not keep them from the park. In 1932, the Cubs increased the number of Ladies’ Day tickets to 20,000, claiming “another thing that impresses us is the loyalty of the women for the team, no matter how tough the going is. Some of the women are more loyal to the team than they are to the old man, who is probably at home wondering when in hell he’s going to get his supper.”9 As with all things pertaining to female fans, men could not go without commentary, but in the absence of internet jabs, they resorted to physical ones. One man gave his wife two black eyes after she returned home from a game too late to feed him at his preferred time. He was fined $100.10

Throughout the decade, women continued to fill Wrigley in such numbers that offended the delicate sensitivities of male fans. One particularly incensed man took to the DeKalb Daily Chronicle in 1937 to voice his displeasure, preferring women to either stay away from the park or sit like mannequins: “most of the time women are on their feet. Naturally, this works a hardship on the men spectators, because for all their daintiness and sweetness, gals aren’t transparent. So to see what’s going on the men have to stand, too, and this is very wearing and tearing on arches accustomed to being put to use only when something out of the ordinary takes place.” Unfortunately for these men, there is nothing extraordinary about women outsmarting them, and so their plan to attend baseball games at an earlier time to secure front row seats was easily foiled by women arriving even earlier.11

The massive success of Ladies’ Day at Wrigley Field prompted other clubs and sports to invest in such days. Chicago’s horse track, Arlington Park, hosted its first Ladies Day in 1939 and received a record crowd of women who eagerly bought pamphlets and dragged their “men folk” along for the afternoon.12 In addition to offering women a sense of liberation, these Ladies’ Days offered another avenue for the confrontation of class divides and were perhaps the original meeting place of the “woke” white woman. Several women frustrated by the crowds at Ladies’ Day wrote they should be abolished. In response, numerous women defended the practice, arguing “a woman fan…thinks Ladies’ Day should be abolished because she (of course) can afford to pay her way in. She goes every day but wants the privilege taken from women who can’t afford it.”13 Baseball, with the help of women, had succeeded in becoming a game suitable for all (white) Americans.

“I think a lot of women said, Screw that noise. ‘Cause they had a taste of freedom, they had a taste of making their own money, a taste of spending their own money, making their own decisions. I think the beginning of the women’s movement had its seeds right there in World War Two.”

-Dellie Hane, 1943.

During the early 1940s, as America became involved in WWII, attendance dropped, and the MLB toyed with the idea of shutting down the leagues. As a precaution and a means of keeping Wrigley open, Phil Wrigley created a women’s softball league, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League that was featured in A League Of Their Own. By 1944 the league expanded to six teams, all of which drew decent attendance. This new past-time, though, did not detract from the Cubs, and although attendance was down across the Majors, the Cubs still drew an average of 7,000 fans per game, good for 3rd in the league.14 It is also in the late 1940s, post-segregation, that Wrigley’s crowd began to diversify and large numbers of black women and men attended, particularly when Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers were in town.15

Post-WWII and throughout the 1950s, the Cubs saw an attendance spike that brought the totals back up to 1920s levels. However, the decade ushered in a more demure America centered on the nuclear family, and while women did not stop attending games, they lost part of their status as legitimate fans. In a particularly feminist article, Tribune writer Edward Burns writes, “we have never seen a homely female in a Ladies’ Day turnout…occasionally we have eyed one that might not have been quite what she used to be.” He further recognizes women’s contributions to society in applauding WWII for pushing forward the start times of games from 3pm to 1:30 so that no husband will be “stuck with a cold snack or no supper.”16

Male sportswriters became increasingly concerned with female fans as the decade

Male sportswriters became increasingly concerned with female fans as the decade

progressed, and a number of stores started Ladies’ Day to capitalize on its success in the sporting world and lure away women from the ballpark and into the shopping malls. Women once again were boiled down to their appearance via writers concerned they would be unable to grasp the intricacies of professional baseball and ads that guaranteed them free admission in exchange for looking pretty and smiling. Wrigley became a gathering place for like-minded women to exert the independence they lost in the household.

“When you’re a Cub fan, it doesn’t make any difference to me. I always thought girls could yell louder than boys.”

-Ernie Banks, Chicago Tribune, June 27th, 1969.

The 1960s ushered in the Civil Rights era, a time that combined women’s rights with black rights and anti-war movements. After signing Ernie Banks, Chicago and Wrigley Field gradually began to further diversify. Over the past 30 years, women’s rights had taken a backseat to the Great Depression and WWII, but the 1960s brought it back into the spotlight and coupled it with reproductive and sexual rights legislative acts. All the while, women continued to flock to Wrigley Field and began to flock to baseball writing, as well. The ‘60s changed the character in which women fans were typically viewed and brought an acceptance to both new and old fans alike. One Tribune reporter, Sheila Wolfe, wrote in 1963 about both old and new fans, recounting an age of women “with scorecards in their laps, transistor radios to their ears” helping new female fans understand the game.17

By the time the 1980s rolled around, Ladies’ Days had been banned due to gendered discrimination, but by that point, the Cubs had largely secured a vast fanbase comprised of dedicated women and men. Indeed, the Tribune ran a piece in 1980, titled “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend.” Portrayed as typical fans, the women interviewed in this piece discuss the anger they feel when forced to miss a game and the lengths they go to in order to leave work and catch games at Wrigley. In line with the progress made through the ’60s and ’70s, the author surmises that women will soon move up the ranks into front office positions and into the broadcast booth.18

The history of Ladies’ Day accurately depicts the struggles female fans continue to encounter today, except they left the ballpark with far less pink memorabilia. It is clear, though, that female fans, particularly Cubs fans, have struck a dialogue with politics throughout history. So if you find yourself at a game in early April and are surrounded by women in jerseys and pussy hats, high five them and offer to buy them a beer, because they will ultimately determine your experience as a Cubs fan and as a citizen of this country.

Lead photo courtesy Jerry Lai—USA Today Sports

1 Chicago Daily Tribune, June 6, 1919.

2 Stuart Shea, Wrigley Field : The Long Life and Contentious Times of the Friendly Confines, 175.

3 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs, 214.

4 Roberts Ehrgott, Mr. Wrigley’s Ball Club : Chicago and the Cubs during the Jazz Age, 55.

5 Lisa G. Materson, For the Freedom of Her Race: Black Women and Electoral Politics in Illinois, 145.

6 Ehrgott, 8.

7 The Brooklyn Eagle, August 7, 1929.

8 Chicago Daily Tribune, June 6, 1932.

9 Chicago Daily Tribune, August 23rd, 1932.

10 DeKalb daily chronicle, August 28th, 1937.

11 The Rosselle Register, July 7, 1939.

12 Chicago Daily Tribune, August 20, 1930.

13 Shea, 230.

14 Brent Staples, “Where Are The Black Fans” in The New York Times, May 17, 1987.

15 Chicago Daily Tribune, May 27, 1951.

16 Chicago Daily Tribune, June 8th, 1963.

17 Chicago Daily Tribune, April 10th, 1980.

Great article Mary! Thank you!