Being a baseball fan is incredibly time-consuming. Not only do you have to set aside 3 hours every day for the game, you also have to set aside time in the summer to think of excuses to miss gatherings and appointments in favor of watching baseball and in the winter to spend moping about the lack of baseball. To non-baseball fans, this all seems crazy and like a complete waste of time. I have been asked on a number of occasions what’s so great about baseball and why I’m not doing something better with my time. I’ve always either sidestepped this question or given a 15-minute soliloquy about how baseball is art and life, but this rarely satisfies the interrogator and instead makes me seem slightly more insane than I actually am. So I’ve recently spent some time thinking about these questions and how in this political climate I can continue to dedicate so much time to something seemingly so trivial. I think the answer becomes clear when we take a look at Mr. Cub himself, Ernie Banks.

The push to desegregate baseball began in the late 1930s when a group of black sportswriters gathered together to write open letters to owners and poll active players. The movement gained momentum in the early 1940s when civil rights groups latched onto it and launched daily protests outside major ballparks, including Wrigley Field, gathering over 1 million signatures in the process. After nearly a decade of relentless campaigning and protesting, Jackie Robinson stepped onto the field as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers and as a triumph for desegregation. And six years later, the Chicago Cubs welcomed their first black player, Ernie Banks, to the team.

Recognized by many as a hero, Ernie Banks stands as the most popular–and greatest–Cubs player in history. He commanded the infield and the plate, compiling 512 home runs, 2583  hits, and back-to-back MVP awards over his 19-year career. He quickly became a fan-favorite, offering a spark to a stagnant franchise. His eternal optimism and unwavering love for baseball drew people to him. Cubs fans latched onto his enthusiasm, and his trademark saying, “Let’s play two!” was plastered all over Chicago for much of his career and beyond. Speaking of his first time at Wrigley, Banks recalled, “I didn’t want to leave the park. It just captured me, it just grabbed me – said this is the place you need to be, like it was talking to me, the park itself. This is your place. This is the place where you do all the things you need to do in the game. And I just fell in love with it.”1 This attitude permeated everything he did in a Cubs uniform, and Cubs fans grew to love him for it; even as a member of losing teams, Banks’s love for the game never wavered.

hits, and back-to-back MVP awards over his 19-year career. He quickly became a fan-favorite, offering a spark to a stagnant franchise. His eternal optimism and unwavering love for baseball drew people to him. Cubs fans latched onto his enthusiasm, and his trademark saying, “Let’s play two!” was plastered all over Chicago for much of his career and beyond. Speaking of his first time at Wrigley, Banks recalled, “I didn’t want to leave the park. It just captured me, it just grabbed me – said this is the place you need to be, like it was talking to me, the park itself. This is your place. This is the place where you do all the things you need to do in the game. And I just fell in love with it.”1 This attitude permeated everything he did in a Cubs uniform, and Cubs fans grew to love him for it; even as a member of losing teams, Banks’s love for the game never wavered.

Paired with his love for baseball was his love for America and his love for humanity. The latter two propelled him out of Chicago in 1968 and into the Mekong Delta in Vietnam to greet US troops. One soldier, Doc Schuebel, a Cubs fan from Milwaukee, was struck by the way Banks carried himself, calling him a “class act.” Although the meeting only lasted a few short hours, it greatly impacted Doc, who carried the photo with him everywhere hoping to tell people about his 15 minutes…in the sun with a hero.”2 Of his time in Vietnam, Banks had little to say, except to praise the troops and remark, “young people, when they’re called upon, can do the job.”3 And young people did the job. They consistently filled Wrigley during the late ‘60s to admire Banks.

This mutual love between Banks and the fans, however, was tinged with uneasiness on both sides. Playing in front of majority white crowds, Banks and Gene Baker frequently had conversations that concluded with the observation, “Ernie—there’s only two blacks in this ballpark. We gotta get outta here!” Recalled Banks, “the sudden association with so many white people often left me speechless and wo ndering why they were so kind.”4 While the Cubs were the sixth team to integrate and the first to hire a black scout and coach, for much of Banks’s career, he was the sole long-term black player on the team. Because of his light-hearted personality and agreeable nature, white fans viewed him as a non-threatening black player they could more easily support. He rarely engaged in political speech or demonstration, preferring to rather be “just a human being” living his life. His baseball excellence helped ease white Chicagoans into accepting black people without having to do too much.

ndering why they were so kind.”4 While the Cubs were the sixth team to integrate and the first to hire a black scout and coach, for much of Banks’s career, he was the sole long-term black player on the team. Because of his light-hearted personality and agreeable nature, white fans viewed him as a non-threatening black player they could more easily support. He rarely engaged in political speech or demonstration, preferring to rather be “just a human being” living his life. His baseball excellence helped ease white Chicagoans into accepting black people without having to do too much.

It was easy for white people to attach themselves to Banks because he was jovial and non-threatening, one of the “good blacks.” His presence created numerous anecdotes like this one described by Buck Wargo:

My traveling to other neighborhoods brought me in contact with not only the boys my age, but also their fathers. One experience came as a shock to my system when the dad of one my friends for some reason — I can’t recall why today — started criticizing blacks in language I had never heard before.

I thought he must have been joking, but I quickly learned he wasn’t. How could this man hate a whole group of people and those he hasn’t even met? It wasn’t a pleasant experience, but it was eye-opening.

It wasn’t my last interaction with him, because I would sometimes go to my buddy’s house to watch the Cubs play and he would be there. He was an intimidating man and you never felt comfortable striking up a conversation with him.

I thought I’d just need to stick to talking about baseball to stay on safe ground. There’s nothing safer than the Cubs, since he was a big fan. I was shocked when he said Ernie Banks was his favorite Cub and how he talked about him in such glowing terms, like he was a member of the family.

In this sense, Banks was the baseball equivalent of the “I have a black friend!” defense. While Chicago remained largely segregated, Banks did not encounter much trouble from white people because he was able to entertain them. Longtime Cubs fan Pete Mundy reflects this simplistic view of race surrounding Banks: while waiting outside the Cubs’ locker room after a game, out stepped “‘a big black man in a sharp-looking business suit.’ It was Ernie Banks who introduced himself and signed their programs. ‘That’s what I’m here for,’ he said. ‘We were two young white boys,’ who felt that ‘Ernie Banks transcended centuries of prejudice’” in that interaction.5

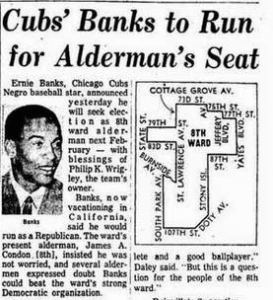

But still, as a black man in America, Banks was certainly not immune to criticism, and his apparent lack of engagement in the Civil Rights movement painted him as a target. Sports Illustrated writer Mark Kram  summarized the disappointment felt by people toward Banks’ apolitical life as such: “Banks does not appear to have much clout among the blacks. His lack of militancy bugs them, but, more important, they feel he is not part of The Cause.6.” But when Banks decided to run for city office in 1962, he received criticism for not sticking to baseball, as white people drew fearful for black people branching out into other areas of society. On this subject, Banks was adamant to not use it as a crutch, proclaiming, “I don’t think it’s up to black athletes to get involved in political or racial issues. Our main objective should be to play whichever sports we are involved in and play well…An athlete, like everybody else, had to live with himself. It is not his duty to comment on things outside of his game or to bum-wrap somebody else in airing his personal feelings.”7

summarized the disappointment felt by people toward Banks’ apolitical life as such: “Banks does not appear to have much clout among the blacks. His lack of militancy bugs them, but, more important, they feel he is not part of The Cause.6.” But when Banks decided to run for city office in 1962, he received criticism for not sticking to baseball, as white people drew fearful for black people branching out into other areas of society. On this subject, Banks was adamant to not use it as a crutch, proclaiming, “I don’t think it’s up to black athletes to get involved in political or racial issues. Our main objective should be to play whichever sports we are involved in and play well…An athlete, like everybody else, had to live with himself. It is not his duty to comment on things outside of his game or to bum-wrap somebody else in airing his personal feelings.”7

As the Civil Rights movement pushed forward, inch by inch, and criticism of him grew more vocal, Ernie Banks continued to live his life on his own simple terms. He continued to be welcomed by 30,000 adoring fans at the ballpark, and if he felt unwelcome away from the park, “I’ll just go elsewhere, but I’m not going to…change my life.”8 He became the model of consistency in all his ventures, particularly unkind to opposing pitchers and overwhelmingly kind to opposing human beings.

In an NPR interview in 2009, Banks discussed being awarded a medal of honor at the Library of Congress, asserting it was fairly meaningless. “I always had a bigger goal when I was 15, and that was to win the Nobel Peace Prize,” stated the Hall of Famer, “and I think about that a lot. I dream about it. I see myself in Stockholm. That has been my journey. I mean I’ve been chasing the footsteps of my life to do something worthwhile. I haven’t done anything yet. I have not done anything yet.” While it is perfectly Ernie to downplay his achievements, this particular revelation seems to mark a departure from his playing days in which—aside from kissing a white woman on a tv show—he remained rigidly apolitical. But, in such a racially charged time and place, merely existing was a political statement, let alone playing baseball at a remarkably high level. And his kindness only enhanced his political nature.

After his death on January 23rd, 2015, thousands of Cubs fans gathered on social media and in Daley square to pay tribute to him. Those not old enough to have seen him play recounted stories about how much their parents and grandparents loved him. He was remembered for his incredible baseball career, his dedication to the Cubs, and his dedication to Chicago: “While Ernie Banks was Mr. Cub and always known as Mr. Cub, the fact he is now and always will be and always has been Mr. Chicago.”9

Ernie Banks personifies the journey many baseball fans, like myself, take. Growing up in a fairly rural part of Canada, for years the only time I encountered black and Latino people was while watching baseball. I grew up idolizing Pedro and Griffey Jr. When they triumphed, I did, too, and when they failed, I felt like I had, too. I quickly became superstitious and did whatever I thought I could do to help my team win (it didn’t work), because I connected with the players–all players–and wanted them to succeed. I learned the significance of equality while allowing for those most talented to shine.

It is easy to criticize Ernie for apparently refusing to use his platform to further Civil Rights discourse when so few of us have been in the position where doing so could end our careers or endanger our lives. And so, perhaps despite his best efforts, Ernie Banks lived a deeply political life. His eternal optimism and resiliency reflect the best qualities of humanity, and the impact he had on Chicago demonstrates the purpose of baseball. It’s not an escape from politics, because it crafts our personalities and our democratic outlook. It forces us to eventually confront issues of race, and class, and gender. It exposes the prejudices we hold, and at its best, it forces us to realize we need to “play two,” to play for those who look like us and those two don’t.

1 “Ernie Banks Still Swinging For ‘Worthwhile’ Life.” NPR Morning Edition, October 13, 2009.

2 Pam Grimes and Steve Sanders, “The Untold Story of When Ernie Banks Went To Vietnam,” in WGN, November 10, 2015.

3 Phil Rogers, “Ernie Banks: Mr. Cub and the Summer of ’69.”

4 Peter Golenbock, “Wrigleyville: A Magical History Tour of the Chicago Cubs,” 350.

5 NPR, 2009.

6 http://www.si.com/vault/1969/09/29/610803/a-tale-of-two-men-and-one-city)

7 Golenbock, 351.

8 http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/if-only-ernie-had-seen-it-heres-why-mr-cub-part-last-nights-win-180961005/.

9 Daily Herald, January 28, 2015.

Lead photo courtesy Dennis Wierzbicki—USA Today Sports

I met Ernie at a party thrown by Remy Martin in LA during my time playing summer pro/am basketball. He was as gracious and engaging as you could imagine. He also was smaller than I expected as I remember him from my perspective as a child looking up to him and Sweet Billy Williams at Dodger Stadium picture day. He was my size and I remarked it was surprising he could have hit so many HRs.