It’s always ones of baseball’s greatest gifts to fans (and writers) when one game or moment stands as a summary of a player’s career. Popular plays include Jeter’s flip in game 3 of the 2001 ALDS, “The Catch” by Willie Mays, and Nolan Ryan punching Robin Ventura. In 1955, Cubs pitcher Sam Jones created another one of these moments when he became the first black player to throw a no-hitter.

After toiling away in the Negro Leagues, minor leagues, and winter ball for five years, Jones made his MLB debut for Cleveland in 1951, but only pitched in two games that year. The following year, he appeared in 15 games, but only pitched 36 innings. In the offseason, he injured his arm (officially bursitis, but medical reports were sketchy back then, so it could have been a number of ailments), requiring him to be shut down and assigned to the minors for the next two seasons. Despite having an exceptional curveball (“You’ve never seen a curve ball until you’ve seen Sam Jones’s curve ball. If you were a right-handed hitter that ball was a good four feet behind you,” says Hobie Landrith, Jones’s catcher with four teams)1 and a hard fastball, he could not stay healthy and suffered from wildness, posting a 2.08 WHIP in his 36 innings in 1952. After an arduous two years of rehab and a voicing of his displeasure at being stuck in the minors, Jones was traded to the Cubs in September 30th, 1954 for Ralph Kiner and PTBNL.

Through the first starts of the 1955 season, Jones was 3-3 with an ERA over five, and he would finish the season 14-20, leading the MLB in losses, as well as both strikeouts and walks (a feat he accomplished 3 times in his MLB career). Although he was considered the ace of the Cubs’ staff and even made the All-Star team, it was probably his worst of 13 major league seasons (which was fitting for the 1950s Cubs, who loved watching former players have their best success elsewhere). There was no indication that his start on May 12th against the Pirates would be anything special, and thus only 2,918 fans got to witness history.

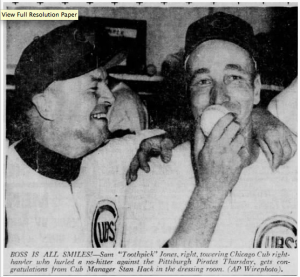

Because baseball is largely driven by narrative and lore, Sam Jones’s affinity for toothpicks must obviously come into play. He was nicknamed Toothpick Sam (which was actually the far better of his two nicknames, the other being “Sad Sam,” stolen from the 1920s pitcher Sam Jones) because he was tall and thin and always chewed one. He usually bought several boxes at a time and went through a number of different toothpicks during each game.2 His affinity for toothpicks was well-known across baseball, and in 1957, Cardinals’ GM Frank Lane promised him a golden toothpick if he won 20 games that season.3 Lane probably got the notion to bribe Jones with toothpicks from WGN-TV’s Harry Creighton, who told Jones in BP on May 12th he would buy Jones a solid gold toothpick if he no-hit the Pirates.4 Despite living a simple life and favoring regular toothpicks over flashy (colored or flavored) ones that easily “bust up,”5 the promise of a golden toothpick proved too tempting to ignore.

The no-hitter began routinely enough, and the Cubs led 4-0 going into the ninth. Having walked four and struck out three, Jones was at 109 pitches entering the inning and had no idea he was even throwing a no-hitter. However, his wildness reared its head, and he walked the first 3 batters he faced (Gene Freese, Preston Ward, and Tom Saffell) bringing up the heart of the order with the bases loaded and no outs. At this point, Cubs manager Stan Hack went to the mound to see if there was an issue. The ever loquacious Toothpick Sam replied he was “fine”, and after telling him to “just get the ball over the plate and let them hit it,” Hack left the fate of the game in Jones and catcher Clyde McCullough’s hands, not mentioning Jones would be pulled if he walked another batter.6

Facing Dick Groat, who had nearly got a hit in the seventh, Jones fanned him on three called strike fastballs, one of only 26 Ks for Groat that season. He then struck out Roberto Clemente swinging on two curves and a fastball, leaving Frank Thomas between Jones and history. “I threw him a curve,” recalled Jones, “he swung and missed. I wasted a fastball. I then threw him another curve, high and outside. He swung and missed. Then another curve. He took it and it broke over the plate.”7 Not one for the spotlight, Jones walked off the mound, chewing the same toothpick he had been all game, ready to give all credit for the no-hitter to McCullough, as he was the brains of the operation and Jones merely “threw curves and fastballs.”9

strike fastballs, one of only 26 Ks for Groat that season. He then struck out Roberto Clemente swinging on two curves and a fastball, leaving Frank Thomas between Jones and history. “I threw him a curve,” recalled Jones, “he swung and missed. I wasted a fastball. I then threw him another curve, high and outside. He swung and missed. Then another curve. He took it and it broke over the plate.”7 Not one for the spotlight, Jones walked off the mound, chewing the same toothpick he had been all game, ready to give all credit for the no-hitter to McCullough, as he was the brains of the operation and Jones merely “threw curves and fastballs.”9

The performance not only won Jones a golden toothpick, a gold watch, and $1,000—it also made him a legitimate player in the eyes of many Cubs fans.8 For those who love small sample sizes and pitcher wins, Jones’s performance was even more special because it made him a viable ace. Indeed, the sentiment among many Cubs’ sportswriters was that Jones must be the new staff ace because “Jones had a 4-3 record compared with 1-2 for [then-current ace Bob] Rush.”10 At the time, this was enough.

Two months later, Jones pitched in the All-Star game, where he easily retired Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra in the eighth inning before hitting Al Kaline and walking Mickey Vernon and Al Rosen to load the bases (cementing himself as the original Daisuke Matsuzaka). He repeated as strikeout and walk leader in 1956 and then in 1958 with the Cardinals. His best year came in 1959 with the Giants when he led the league in wins (21) and ERA (2.83). He ended his career in 1964 with the Baltimore Orioles, having amassed a career record of 102-101 across 13 seasons.

Although he did not remain with one team long enough to gain wide fan support and enter into any one team’s lore, he was known by major leaguers and negro leaguers alike as having one of the best curveballs in baseball and being unafraid to go after hitters (he led the league in hit batters in 1955 with 14, one of which came in his no-hitter). Although he did not begin playing baseball until he joined the Air Force at the age of 17, he enjoyed a career that had a little bit of everything in it. His career was as wildly unpredictable as his pitches were unpredictably wild, and his no-hitter combined the two perfectly.

Lead photo courtesy Jerry Lai—USA Today Sports

1 (Schwarz, John H. “Sam ‘Toothpick’ Jones.” The National Pastime, Annual 2002.

2 Statesman Journal, March 16, 1955

3 The Courier News, March 2nd, 1957

4 http://www.si.com/vault/1960/04/11/590348/a-toothpick-for-the-pennant

5 Stuart Shea, The Long Life and Contentious Confines of Wrigley Field,” 259.

6 John H. Schwartz, “Sam ‘Toothpick’ Jones.” The National Pastime, Annual 2002

7 Schwartz.

8 Chicago Tribune, May 29, 1955.

9 Ibid.

10 Statesman Journal, May 14, 1955.