AG Spalding’s preoccupation with making baseball America’s game began perhaps in 1874 when he toured Great Britain with the White Stockings. The trip achieved limited success, but its potential led Spalding to plan another, more vast trip in 1888. He gathered the Chicago White Stockings and various opposing players called the All-American team, and set out, hoping to dazzle the world with the sport. The two teams played 54 games on five continents over the span of six months. This trip coincided with the reintroduction of “manifest destiny” and was a springboard for the term and country’s migration to international imperialism.

In 1885, Protestant missionary Josiah Strong released his best-selling book, Our Country, in which he espoused the crux of manifest destiny: “My plea is not, Save America for America’s sake, but, Save America for the world’s sake.”1 “Save America” translated to “reclaim it for white people.” Millions of acres of land was stripped from Native Americans, and by 1890, the majority of the West was “settled”. A growing economy based on manufacturing and an increasing number of conflicts with the British in the Caribbean led President Grover Cleveland to reassert America’s dedication to the Monroe Doctrine, the 1823 document that declared the Western hemisphere America’s sphere of influence. By the mid-1890s, America began to look further outward, climaxing with the 1898 Spanish-American war, American imperialism’s coming out party. Sandwiched between Strong’s book and the Spanish-American war was Spalding’s tour, the introduction of America to the East.

He wrote that they received welcoming crowds everywhere, although it was primarily the “American colony…out in full force” while the locals in most places “did not seem to catch on to any appreciable extent.”2 Their most triumphant receptions were in Australia and England, the two closest cultural connections. One Australian journalist wrote that he hoped the games would signify a “mutual friendship between two island continents.”3

Although the success of the tour was middling, Spalding claimed it a great achievement for America. He argued it gave 4 Long before the complex world of international relations was created in the 1900s, Spalding used this tour as a means of establishing nationalism.

4 Long before the complex world of international relations was created in the 1900s, Spalding used this tour as a means of establishing nationalism.

Though America held significantly fewer colonies than many imperialist nations, this tour pointed toward the future of America as an imperialist country, fueled by the false flags of exceptionalism and racial superiority. In the years prior to the trip, professional baseball had become a purely white American sport. In 1883, White Stockings field leader Adrian “Cap” Anson refused to play with or against African Americans on the Toledo Blue Stockings. Prior to the teams’ next meeting, Chicago’s press secretary wrote Toledo’s manager, saying “the players do most decisively object and to preserve harmony in the club it is necessary that I have your assurance in writing that [Walker] will not play any position in your nine July 25. I have no doubt such is your meaning[;] only your letter does not express in full [sic]. I have no desire to replay the occurrence of last season and must have your guarantee to that effort.”5 Shortly thereafter, Toledo released the two African American players on its roster, purging the league of such players. Anson was not the only one of this mind, and soon both the National League and the American Association were all white.

This derision toward people of color seeped into every element of the trip, and what was labeled as a baseball exhibition became an exhibition in false superiority. Beginning with Hawaii and moving clockwise across the globe, Spalding and the players encountered a number of “natives” they belittled and gawked over. Anson characterized King Kalakaua of Hawaii as “not a bad-looking fellow, being tall and somewhat portly, with the usual dark complexion, dark eyes and white teeth, which were plainly visible when he smiled, that distinguished all of the Kanaka race,” and all other accounts also focused on appearance, primarily skin color.6

This focus on appearance was accompanied by a disregard for customs and cultures. Of the Samoans, Anson noted their “copper colored skin” and said he could not vouch for their apparent “charm of appearance and manner, combined with greater mental capacity.”7 Conversely, Spalding praised the Australian sportsmen for possessing “all those essentials of manliness, courage, nerve, pluck and endurance, characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon race.”8

This focus on appearance was accompanied by a disregard for customs and cultures. Of the Samoans, Anson noted their “copper colored skin” and said he could not vouch for their apparent “charm of appearance and manner, combined with greater mental capacity.”7 Conversely, Spalding praised the Australian sportsmen for possessing “all those essentials of manliness, courage, nerve, pluck and endurance, characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon race.”8

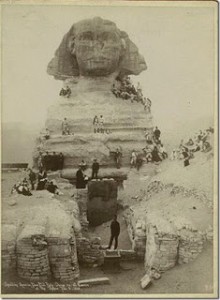

This connection between skin color and intelligence persisted in the group’s accounts of their journey across Asia and Africa. Chicago’s pitcher, John Tenet, described Indians as all having dark skin and of the nature that “you get tired of looking at the native worshippers.”9 In Egypt, after the game, the American entourage “was photographed en groupe on the Egyptian Sphinx, to the horror of the native worshippers of Cheops and the dead Pharaohs.”10 The flippant and belittling way Americans had dealt with Native American and African American cultures was now being spread throughout the world.

As the trip made its way through Europe, the commentary became friendlier and more respectful. Spalding called Rome “one of the most enjoyable [visits] of the entire tour, so much was there to see of historic interest.”11 And although he wrote little on Paris, he remarked about the wonder of playing under “the great Eiffel Tower,” paying more respect to this Western creation than to the Egyptian pyramids.

The tour concluded in England, where the entourage received their largest crowds. However, many Englishmen insisted their interest in the game stemmed from its likeness to games they had invented, namely rounders and cricket. Ever the patriot, Spalding hoped to put the kibosh on these claims by challenging England’s premier rounders team to a game of rounders followed by one of base ball. The Americans picked up rounders fairly quickly, losing the game by only three runs. The baseball game, however, was entirely different. “Three Englishmen struck out and then the Americans went to bat,” recounts the Reading Times. The Americans’ at-bat lasted so long, “the first inning in the baseball game never finished; yet the score stood 35 to 0 in favor of the Americans.”12

Even while trying to distance America from England, Spalding heaped praise on the Englishmen, noting their qualities of “dignified courtliness, amiable courtesy, tactfulness, and honest conviction” made them the perfect hosts.13 Those who most closely resembled white Americans received the most praise, while those who least resembled them were treated at best as amusing spectacles.

Summarizing America post-tour, Spalding wrote,“ever since its establishment in the hearts of the people as the foremost of field sports, Base Ball has ‘followed the flag.’ It followed the flag to the front in the sixties, and received then an impetus which has carried it to half a century of wondrous growth and prosperity. It has followed the flag to Alaska…it has followed the flag to the Philippines, to Porto Rico and to Cuba, and wherever a ship floating the Stars and Stripes finds anchorage to-day; somewhere on nearby shore the American National Game is in progress.”14 The baseball tour signified the beginning of and became synonymous with American imperialism.

1 Josiah Strong, 107–108.

2 Spalding, 259.

3 Thomas W. Zeiler, “Ambassadors in Pinstripes: The Spalding World Baseball Tour and the Birth of The American Empire,” 96.

4 Spalding, 265.

5 Howard W. Rosenberg, “Cap Anson 4: Bigger Than Babe Ruth: Captain Anson of Chicago,” 424.

6 Thomas W. Zeiler, “Basepaths to Empire: Race and the Spalding World Baseball Tour,” Society for Historians of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era, 6 no. 2, 191.

7 Ibid., 193.

8 Ibid., 194.

9 Spalding, 258.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid., 259.

12 Reading Times, June 7, 1907.

13 Spalding, 264.

14 Ibid., 14.