On August 25th, 1948, the House Un-American Activities Committee first televised one of its sessions, a stand-off between former State Department official, now-accused Soviet Spy Alger Hiss and former US Communist party member, now-Time Magazine editor Whittaker Chambers. The day, dubbed “Confrontation Day,” grabbed national headlines across the country, promising to be the first of many such days between the two gentlemen and within the HUAC as the country grappled with the growing war between public and private.

The following day, the privately-owned Chicago Cubs had its own public version of Confrontation Day.

On August 26th, the last-place Cubs played a doubleheader against the league-leading Boston Braves. Months prior, on May 31st, the Cubs played a doubleheader against the Pittsburgh Pirates, drawing 46,965 Memorial Day fans in contribution to shattering Major League Baseball’s single-day attendance record. Two months later, a holiday-less, sputtering team, now three-month veterans of last place, drew a crowd half that size for this doubleheader. But the loyal fans in attendance were treated to a spectacle almost as shocking as the Chambers-Hiss conflagration.

The Cubs miraculously won the first game 5-1 on the back of Doyle “Porky” Lade’s best pitching performance of the season. Prior to this start, his second season in the majors had been disappointing, much to the surprise of many Chicago sportswriters who declared it a “mistake” for the White Sox to allow the Cubs to acquire Lade. He was demoted in May, following two miserable outings that revealed the rookie required more coaching than the Cubs could provide. In July, after it seemed likely the team would not contend for the pennant, Lade was recalled and slowly improved at the major league level.1 Though he only remained in Major League Baseball for two more seasons, Lade’s performance this day coupled with its shenanigans prevented his career from being both short and banal.

The second game, featuring rookie Vern Bickford for the Braves and vet eran Hank Borowy for the Cubs, was also expected to produce a victory for Boston. But as improbable as the events of the first game were, the second eclipsed them rather easily.

eran Hank Borowy for the Cubs, was also expected to produce a victory for Boston. But as improbable as the events of the first game were, the second eclipsed them rather easily.

As many extraordinary events do, the game began in a more or less mundane fashion. Bickford cut down the league’s worst offense with relative ease, while Borowy navigated himself in and out of trouble against the league’s best lineup. By the third inning, the Braves had amassed a 1-0 lead, which could have been far larger without an outstanding unassisted double play turned by first baseman Phil Cavarretta. In an instance of truth that precipitates all baseball cliches, the man who had made a sensational defensive play to end the inning quickly came to bat in an important situation. With two out, Emil Verban on second and Hal Jeffcoat on first in the bottom of the third, Cavarretta stepped to the plate. In his 15th season, Cavarretta had finally begun to succumb to age, but in this at-bat, possessing perhaps the best chance of scoring the Cubs would have in the game, he once again demonstrated his legendary hitting prowess. He lined a Bickford fastball into left field, befuddling Jeff Heath, who first failed to catch it and then believed it was stuck in the park’s notoriously partisan ivy.2

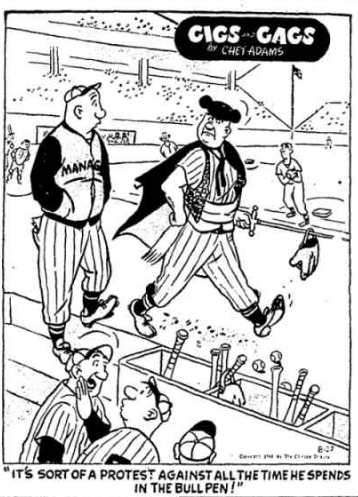

Without signal from the umpire, Cavarretta circled the bases for a three-run inside-the-park home run, the second of his career. Unwilling to be duped by a last place team and its quirky park, however, the Braves protested. Following a short argument and a long conference, the umpires ruled in favor of the Braves, awarding Cavarretta a measly ground-rule double and one RBI. In response to this grave injustice, the crowd erupted, hurling “straw hats, bottles, and paper” across the grandstands and onto the field.3 With no indication the mayhem would cease, Umpire Jocko Conlan, braving the onslaught of verbal and physical garbage, raced across the field to berate the Cubs’ dugout policeman for failing to control the crowd. This action, of course, roused Cubs manager Charlie Grimm from the safety of the dugout, as he could not resist a verbal spar with Conlan. When this argument pittered out, the fans again threw another slew of paper cups, bottles, and scorecards onto the field.

After a lengthy wait, and when it seemed all refuse in the park was now occupying center field, Conlon signaled for the continuation of the game, asserting that any ball hit amongst the paper would be ruled a double. Braves manager Billy Southwarth instantly protested this ruling, refusing to resume the game until the field was cleared of all debris. Unwilling to continue the standoff, Conlon acquiesced. Ironically, after the next batter, Andy Pafko, was intentionally walked, Peanuts Lowrey hit a bases-clearing triple to center field that would otherwise have been a double in the trash-filled park. Now trailing 5-2, Southwarth begrudgingly removed his starter from the game, his defeated presence on the field this time eliciting cheers from the pacified crowd of Chicagoans.

The Cubs held on to win the game 5-2, and in a season defined by lasts, this game was filled with firsts. It was the first and only time the team swept a doubleheader that season, the first time Hank Borowy threw a complete game, and the first time Wrigley housed a riot of such proportions.4 The day after Chambers began something he later dubbed “a tragedy of history,”5 the Cubs ensured that in this tragedy of a season, there would be at least one triumph, for the fans and for those players like Lade whose careers would otherwise have been forgettable.

And so as the rest of the country was consumed by a confrontation of more epic and dire proportions, a showdown that could impact the future of American politics, Chicago created its own version of protest. Before McCarthyism and the fear of ever-present Soviet spies flamed by Confrontation Day seeped into baseball, before anti-Communist riots consumed the country, Wrigley Field and the Chicago Cubs demonstrated that baseball is not so distant from the events taking place in Washington, that those in the ballpark are not so different from those in Congress. In the absence of other means, Americans will fight perceived injustice with paper cups and scorecards.

1 Alton Evening Telegraph, July 30, 1948.

2 Stuart Shea, “Wrigley Field: The Long Life and Contentious Times of the Friendly Confines,” 250.

3 Chicago Tribune, August 27, 1948.

4 Ibid.

5 http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/03/09/reviews/chambers-stolid.html

Lead photo courtesy Patrick Gorski—USA Today Sports

Really enjoyable read Mary. Thank you for this article.