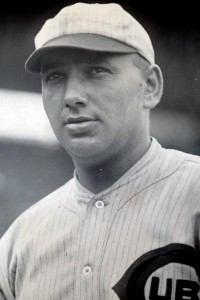

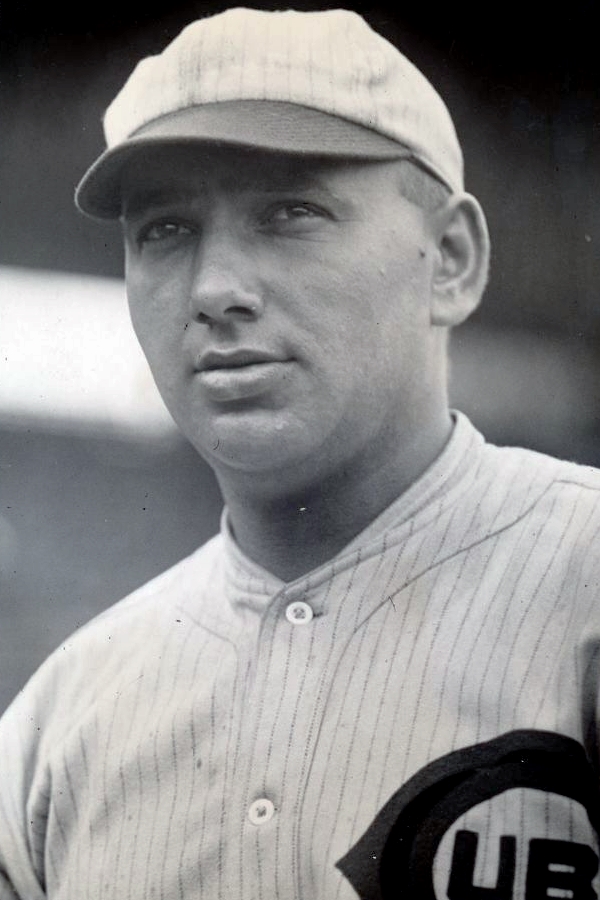

Abraham Lincoln “Sweetbread” Bailey was the third and final of such a name to play professional baseball, following “Ham” Wade and Abe Wolstenholme. None of these three baseball players have much in common with President Abraham Lincoln save for their name, a shared love of baseball, and coincidental dates here and there. Moreover, all three have faded from baseball memory while their namesake lives on as one of this country’s greatest figures. We have a vibrant picture of the latter and only blurry sketches of the former, two groups separated by time and rank. Yet the timelessness of President Lincoln ebbs forward, latching onto these men and filling in their blank spaces, all while offering us a reprieve from our dependency on time.

Of these three baseball Abes, Sweetbread had by far the most illustrious career. Ham Wade appeared in only one game, a 1907 affair between the New York Giants and the Boston Doves in which he played two innings as the Giants’ left fielder. He reached base in his only professional plate appearance, a hit by pitch. Abe Wolstenholme fared somewhat better, his career with the 1883 Philadelphia Quakers lasting a lengthy single week, from June 4th to June 11th. Like Wade, he was a left fielder who managed to get on base once in his career, but unlike Wade, he did so in eleven plate appearances.

Sweetbread Bailey’s career diverged from these two in minor ways and converged in one major way. First, he was a pitcher, secondly, his career spanned parts of three seasons, and thirdly it was delayed due to his time in the military. He could have begun his professional career with the Cubs in 1917, but instead enlisted in the 72nd Field Artillery, returning at the end of the war. The Cubs immediately added him to the team’s roster as a relief pitcher, but his lost conditioning delayed his first appearance by several months.1

Unfortunately, Sweetbread was no better at baseball than his predecessors, and his much-anticipated career was likely not worth the wait. He played his first game with the Cubs on May 23rd, 1919, pitching one shutout inning against the Philadelphia Phillies, and his final game on June 11th, 192 1, with the Brooklyn Robins, allowing one run in one inning of work. In total, Sweetbread pitched 137 and one-third innings, allowing 70 runs on 171 hits for a bulbous 4.59 ERA.

1, with the Brooklyn Robins, allowing one run in one inning of work. In total, Sweetbread pitched 137 and one-third innings, allowing 70 runs on 171 hits for a bulbous 4.59 ERA.

We know little else about this man. We do not know what happened to him after his career, why he decided to play baseball, what he hoped to accomplish in life, or even what he thought of President Lincoln. We know precisely the length of his life but are largely ignorant of its contents, condensing his decades into three years. He is not much more than a name and a series of coincidences, a man who embodied the burgeoning spirit of America reduced to a funny nickname and a “huh, how about that” full name.

In order to piece together more of Sweetbread’s life, we must turn to the man for whom he was named. In contrast to the baseball player lost in the passing of the years, Lincoln himself was a master of time, understanding its limitations and using its capriciousness to his advantage. He always kept one eye glued to the ticking second hand of the clock while the other wandered decades into the future, locking onto people just like Sweetbread. Indeed, Lincoln’s most famous speech begins with a declaration of time, “four score and seven years ago,” but is much more a rumination on the timelessness of man, and so it is in these words that we can come to know the individual existing decades after Lincoln ceased doing so.

The Gettysburg Address was given on November 19th, 1863, four months after over 7,000 Union soldiers laid down their lives to ensure a victory in the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg. The entire speech is a meagre 272 words long, discussing a specific moment in time, but going far beyond that. Somewhat ironically, considering the fame of these words, Lincoln early on states that “the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here;” the speech is likely to fade into the background while the lives of these men will be remembered forever. Four months ago, those soldiers came to the end of their time, and it is now up to every American to advance their effort into the future, to ensure the country will “have a new birth of freedom…[that] shall not perish from the earth.”2 Time, then, becomes something less definite; its ends create beginnings and each beginning carries with it the possibility of timelessness. And peculiarly, it is in this ability to transcend time that we can derive what it means to be a human being.

Sweetbread Bailey was named Abraham Lincoln because he was born on February 12th, Lincoln’s birthday. His first start, May 23rd, is the same day Lincoln wrote to Congressman George Ashmun to accept the nomination for the upcoming presidential election. He, rather unknowingly, embodied the words Lincoln spoke at Gettysburg, fighting for the same freedom the president espoused. What we know of his life, therefore, corresponds to Lincoln’s, linking them and giving each a purpose and a life outside his own. President Lincoln is catapulted into the 20th century while Sweetbread is drawn back to the Civil War. The vastness of Lincoln, the person and figure, transfers to Sweetbread, and we begin to see a person who exists outside of his three years as a Major League Baseball player.

We move with Sweetbread through his first start, his first victory on June 20th against the Brooklyn Robins, his appearance at Warren G. Harding’s 1920 campaign exhibition game, his trade to Philadelphia in 1921 for cash, and his final professional baseball appearance in 1923 with the single-A Beaumont Exporters, a journey lasting four years and thousands of miles. Ordinarily, a person of such slim record would be reduced to a handful of moments compiled from date-stamped newspapers, securely affixing them to a specific moment in time. But it is possible for Sweetbread to be saved from this fate, due to his namesake. The words of the Gettysburg Address burst through the 19th century, calling out to Sweetbread, and suddenly he is not just a name to remember, but a person to remember.

1 Bill Lee, “The Baseball Necrology: The Post-Baseball Lives and Deaths of More Than 7,600 Major League Players and Others,” (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003), 17.

2 http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/gettysburg.htm

I have a little more about Bailey here:

https://mightycaseybaseball.com/2015/03/10/mighty-casey-bio-abraham-lincoln-link-bailey/

There were two other pro players named after Lincoln:

Abe Fowler- https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=fowler001abr

Lincoln Stickney- https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=stickn001abr