Following a sterling start versus St. Louis to close out his 2017 regular season, Kyle Hendricks once again dropped his career ERA below three. It was his 100th career appearance and his 99th career start, and it brought his season ERA to 3.03. A year removed from an ERA title and a third-place Cy Young finish, Hendricks drew the doubt of many observers who thought that his 2016 was, at least partially, a fluke. For a portion of 2017, those naysayers might have had a point: Hendricks’s velocity was down several ticks from his already fringy numbers, and a longer-than-expected DL stint due to a hand injury kept the righty out of action from early June until late July.

Down the stretch, though, Hendricks shone brightly and contributed significantly to the Cubs’ strong second half. While Jon Lester faltered, Jake Arrieta and Jose Quintana pitched erratically, and John Lackey got old, Hendricks got better. In 78 second-half innings, Hendricks nearly matched his 2016 ERA by posting a 2.19, while striking out 22.7 percent of hitters and walking just six percent.

Now, Hendricks is poised for a probable Game One start versus the formidable Washington Nationals in the NLDS. How was Hendricks able to find success similar to last year after a disheartening beginning to 2017?

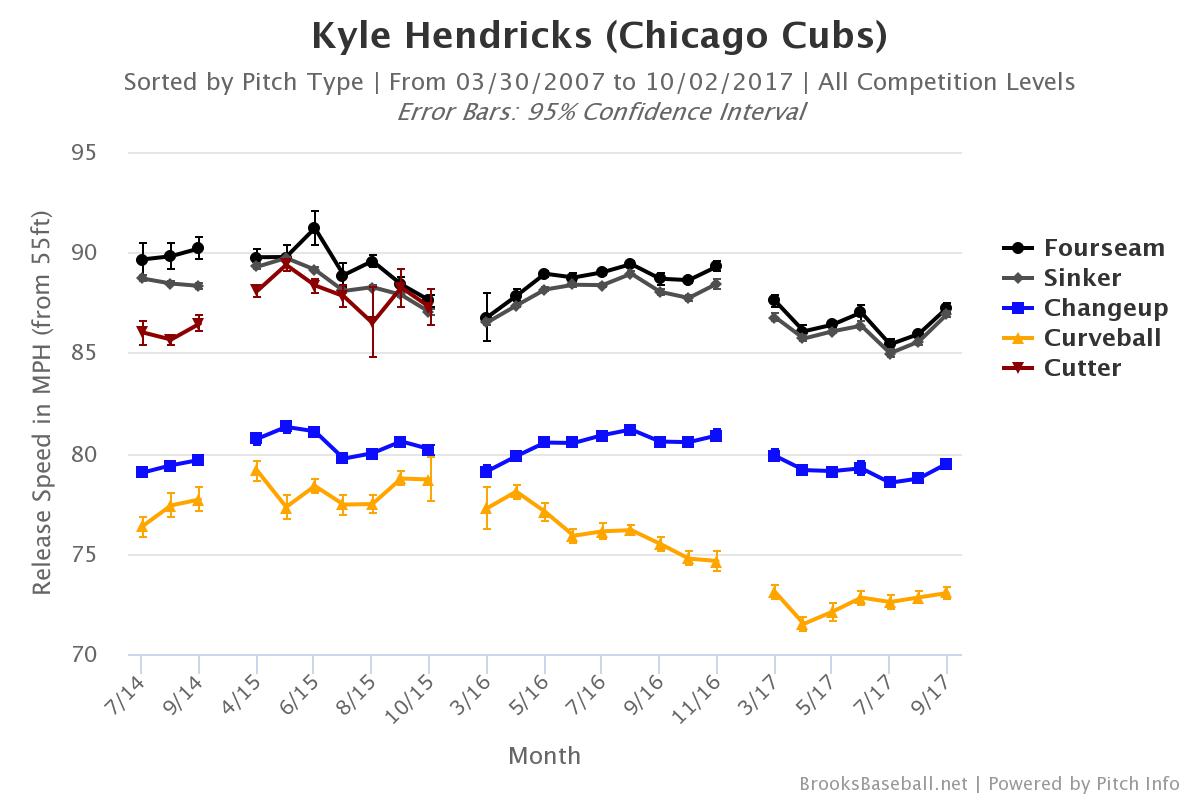

First off, Hendricks slowly ramped up his velocity by September to his highest regular season average since last fall. 85 and 86 showed up on the radar gun too often for the righty most of the year, but by the final month of the year, he was reaching back for 87-plus again. In four of his final five starts, Hendricks found 87-mph on his four-seam fastball, and in three of those starts, he hit the mark with his more often used sinker. This is important, of course–although Hendricks can survive with craft, movement, and cunning, throwing in the mid-80s as a major-league starter is generally untenable.

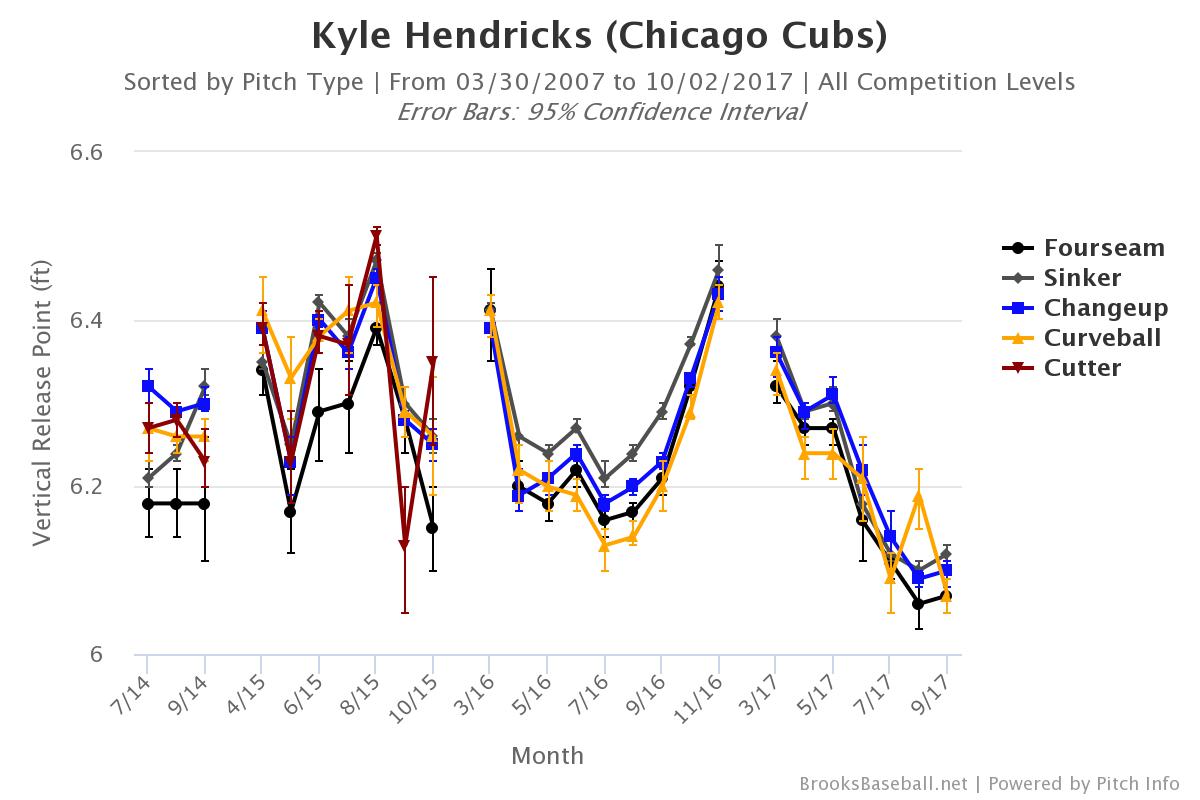

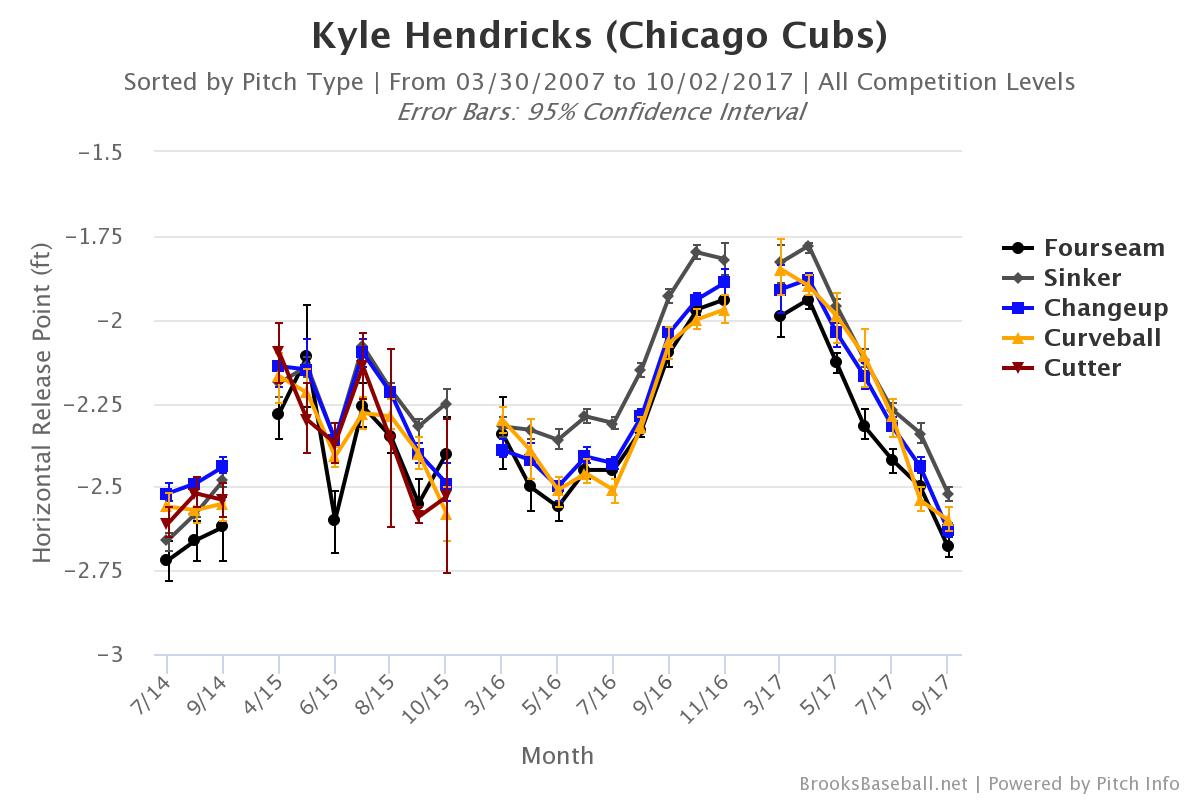

Finding that fastball was not a foregone conclusion for the recovering Hendricks. To regain that velocity, Hendricks had to adjust his mechanics. His arm slot is lower than it has been at any point in his major-league career, and, while pitchers’ arm slots will float from time to time, this appears to have been a conscious effort by Hendricks in the wake of his injury. It’s only a couple of inches of difference, as evinced by the chart below, but it’s a trend.

One would expect that an improvement in fastball velocity has resulted in better performance when throwing fastballs to opposing hitters. With Hendricks, this isn’t this case. The right-hander doesn’t throw his fastball for strikeouts—he relies on his exceptional changeup and his good curveball for that—and hitters aren’t doing much differently versus thefour-seamerr and sinker since Hendricks returned from the DL. Rather, Hendricks’s secondary pitches have seen the improved results.

Since his July 24th comeback start, Hendricks has gained five percentage points in whiffs on his changeup, and has doubled the amount of whiffs on his curveball from three to six percent. Those two pitches have also benefited in the form of a higher percentage of whiffs per swing, indicating general unease that hitters harbor when seeing these pitches from Hendricks. They’re still swinging, they’re just not making contact.

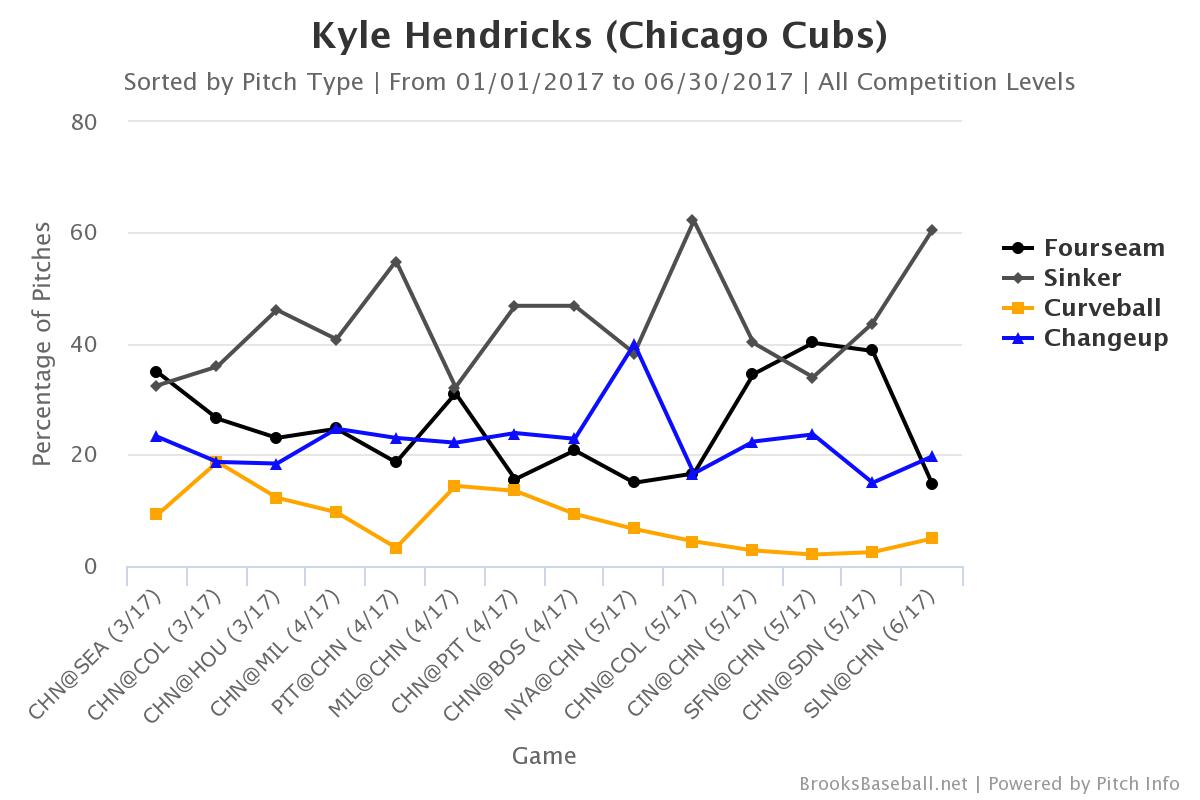

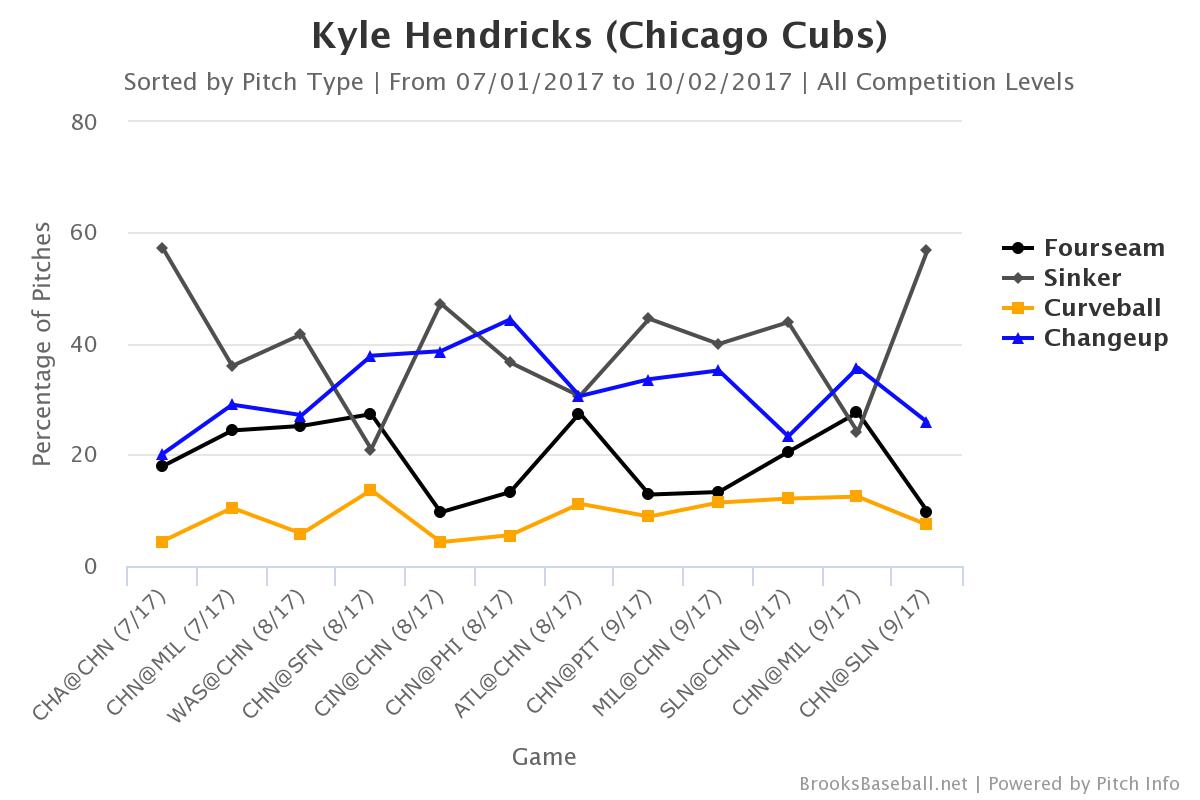

Working in tandem with these swing-and-miss developments is Hendricks’s more varied arsenal of pitches. That is, Hendricks has done well to mix his fastballs, changeup, and curveball much better in the second half. Here are Hendricks’s pitch usage numbers for his pre-DL and post-DL stretches.

In only two starts in the second half has Hendricks thrown his sinker over 50 percent of the time, a number he approached or eclipsed more often in the first half. Instead, he has cut his sinker usage with increased changeup and curve usage. His least-used pitch, the curve, is now closer to 10 percent than the previous 5 percent mark, and his changeup usage is north of 30 percent, whereas it had previously been around 20 to 25 percent. These might not seem like big changes, but, considered together, they represent a shift in not only quality of stuff, but in how Hendricks has decided to attack hitters.

It can be dangerous to suggest throwing one’s best pitch more often. Hitters begin to expect the pitch in certain counts; they sit on it, and what used to be an out pitch quickly becomes the one-trick of the proverbial one-trick pony. For Hendricks, finding a little more fastball velocity has allowed him to deploy his devastating changeup more often. People are obsessed with his change, and for good reason! It’s consistently one of the best in the league, and he manipulates its movement better than any other pitcher in the game right now.

But one pitch does not a Cy Young contender make. As the stats team at Baseball Prospectus has found, Hendricks is an impeccable pitch tunneler. Hendricks has made small gains in his Release:Tunnel ratio for his sinker-sinker and sinker-changeup sequences, his two most frequently used pitch combos. When a master at tunneling improves at that quality, he’s likely to produce good results, and that’s been the case for Hendricks. While we don’t have splits for Hendricks’s tunneling to see how effective he was before and after his DL stint, we can reasonably assume that the improved fastball velocity, more varied pitch mix, and stellar tunneling are the factors contributing to Hendricks’s great second half.

Kyle Hendricks continues to fascinate those who watch him every fifth day and those who just catch him when their favorite team is attempting to make loud contact off his changeup. He suppresses hard contact; he gets more strikeouts than one would expect; and he throws a Bugs Bunny changeup that makes even the best look foolish. If Hendricks is the Game One starter, he’s earned it.

Lead photo courtesy Dennis Wierzbicki—USA Today Sports