Margins of error in the playoffs are thin. So thin. More often than not, games between two evenly matched teams in October turn on the smallest mistakes: a hung breaking ball, a bobbled grounder, a pitcher deployed in the wrong situation. Ah, a pitcher deployed in the wrong situation—there it is, one of the few ways a manager can impact their team’s chances, turning a slight advantage into a chasmic disadvantage just by signaling to the bullpen at the wrong time. Unless the team boasts a many-headed Hydra of late-inning relievers, or a trio of workhorse starters, the manager will inevitably stare down a situation where the personnel in their bullpen doesn’t match the situation staring back. Such is the crucible of playoff baseball.

To gain a slight advantage in the playoffs versus a team like the Los Angeles Dodgers is imperative in a tight series. Sure, an unexpected home run from a role player who didn’t match up well versus the opposing pitcher can render moot the fine tuning of bullpen management or lineup creation, but more often than not one must eek out these slight advantages and capitalize on them in order to bring home a victory. For example: the entirety of the Cubs’ NLDS Game Five in Washington turned on matchups, the right personnel, the wrong mistakes. It was a game of attrition, as so many of these games turn out to be. Joe Maddon found advantages where he could, tossing Jose Quintana into relief for twelve pitches and two quick outs; yanking Mike Montgomery after the lefty showed no semblance of command; pinch-hitting with Kyle Schwarber against hard-throwing righty Ryan Madson. When the home half of the seventh rolled around, the fount of matchups and advantages had dried up. The Cubs, and Wade Davis, weathered a ceaseless offensive attack from the Nationals, securing a victory mostly because time ran out and less so due to outwitting the Washington hitters.

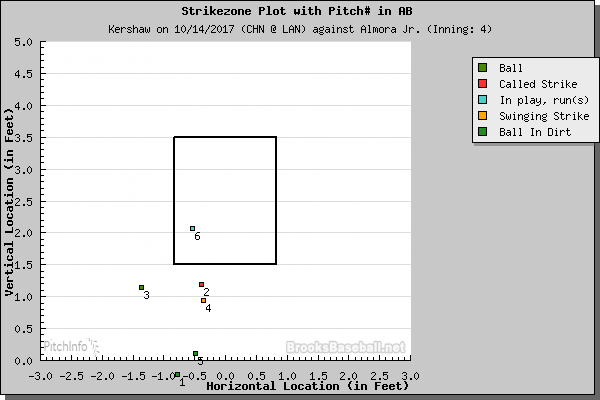

On Saturday, the Cubs eked out some small edge despite being pitted against the best pitcher in the world. Cubs’ hitters put together solid plate appearances versus Clayton Kershaw, laying off his onslaught of fastballs and curveballs off the outside corner and forcing Kershaw to pitch from behind. One of the few advantages the Cubs carried into the game did bear fruit early on, as lefty-mashing Albert Almora smoked a 90-mph Clayton Kershaw slider into the left-field bleachers for a two-run homer. Check out Almora’s at-bat:

That’s impressive work for a young hitter, and even more impressive considering his opponent. A breaking ball in the dirt, a breaking ball catching the very bottom of the zone, a fastball off the plate inside, and three more breaking balls. Almora forced Kershaw to come into the zone by laying off the hard sliders off the plate, and eventually made the Dodgers starter pay. Sound process gave way to favorable results, both on the macro (choosing to start Almora over another outfielder) and the micro (Almora’s approach) levels.

Not long after the Almora home run, Maddon and the Cubs found themselves faced with the dissonance and friction of the wrong personnel for a tough situation. As Dave Roberts boldly removed Kershaw for pinch-hitter Kyle Farmer in the bottom of the fifth, Maddon contemplated his pitching options. Quintana, who had so seamlessly cruised through the first four innings efficiently and effectively, found himself in want of his fastball command in the fifth, surrendering two runs as the result of a pair of walks the bottom of L.A.’s lineup. Having thrown 89 pitches, and with the top of the Dodgers lineup due up in the sixth, Maddon’s slate of options looked like an adventurous all-you-can-eat buffet through the eyes of a picky eater.

A strongly constructed bullpen prior to the playoffs had morphed into a motley, wart-addled crew, and Maddon was hard-pressed to make a decision that didn’t backfire. One hitter later, and the Cubs fell behind for good.

Sunday night, advantages presented themselves more concretely. By the ninth inning, both teams’ hitters had failed to put together a string of hits and walks to plate more than a lonely run, and the tactical advantages gained by choosing the right players, the right pitches, the right defensive positioning grew larger. This time, Maddon felt more confident turning the game over to his bullpen after only 4 ⅔ innings, as Jon Lester had reached the end of his evening prematurely due to 103 high-stress pitches. Carl Edwards, Jr., snapped off a series of curveballs that baffled Dodgers hitters, and the righty attained a small amount of redemption for his lackluster NLDS outings. Pedro Strop turned in a clean inning as well, bridging the gap to the eighth, when Maddon tapped lefty specialist Brian Duensing for two of the Dodgers’ dangerous left-handed hitters.

Duensing muffed a toss from Anthony Rizzo, putting Cody Bellinger on first to start the inning, but was able to escape the inning with a double play off the bat of Austin Barnes. In a crucial situation demanding a LOOGy, Duensing filled his role admirably. To that point, Maddon had deployed his shaky bullpen optimally. Regretfully, that trend did not continue as the ninth inning dawned.

Dave Roberts turned to Kenley Jansen to set the Cubs down in the ninth, as the Cubs sent up the heart of their order. Ugly strikeouts by Kris Bryant and Willson Contreras sandwiched an Anthony Rizzo hit by pitch, bringing up Almora. As mentioned, Almora started both weekend games due to left-handed Dodgers starters—usually, Almora is removed for a right-handed hitter in a tied or losing game. With three lefty bats on the bench (Ian Happ, Alex Avila, and Tommy La Stella), Maddon had the opportunity to match a hitter better suited to face the dominant cutter of Jansen. Instead, Maddon stuck with Almora, who promptly grounded out. An advantage presented itself; an advantage slipped away.

Matters worsened in the bottom half of the inning, when Maddon remained with Duensing to face a torrent of talented righties. With Wade Davis, the club’s best reliever, toiling in the bullpen and reportedly available for an inning, the first-guessers came out in force, questioning Maddon’s decision to stick with Duensing. The lefty allowed a walk and sacrifice bunt before striking out the pinch-hitter Farmer, and once again an opportunity to change the game’s course and gain a meager advantage reared its head, but Maddon fumbled his third consecutive strategic move. John Lackey, pitching for the first time in his career on less than a full day’s rest, entered the game with two outs in the ninth and the top of the Dodgers lineup looming. And so, the compound effects of a starter entering mid-inning with no rest resulted, expectedly, in a walkoff home run to Justin Turner.

The series of decisions is, in short, baffling. Maddon chose not to pinch-hit for Almora because he wanted to double-switch Almora and the pitcher’s spot (then seventh) in the bottom of the inning. That opportunity never came. Maddon chose not to insert his closer in a tie game on the road, later claiming that he was saving Davis for a save situation. That opportunity never came. The Dodgers replaced their best pitcher in the bottom of the ninth with a pinch-hitter, leaving only Tony Cingrani, Ross Stripling, and Kenta Maeda available were the game to go into extras. The Cubs would have had a good shot at plating a run, facing relievers worse than those Roberts had already used. That opportunity never came.

Normally, the individual tactical decisions that a manager makes in the course of a game are both overrated in their importance and over-scrutinized as a result. In NLCS Game Two, with the score tied at one and a possible two-game deficit hanging ominously over the proceedings, those tactical decisions either bequeathed advantages or squandered them. The course of events in the ninth inning reveals the cognitive dissonance inherent in Maddon’s thinking: the Cubs manager worsened his team’s odds at pushing the game into extra innings, or scratching out a lead in the ninth, by choosing objectively worse hitters and pitchers for each scenario. Instead of matching Wade Davis with the Dodgers’ best hitters in the ninth, forcing Roberts to either choose to let Jansen bat and continue to pitch in the tenth or maximize his team’s chance of scoring off Davis, Maddon chose the worst pitcher for the situation and prayed that the game would go to extras via Lackey ex machina.

That is the cruel nature of playoff baseball. Through the forces of managerial tinkering, a slight advantage morphed into a deficit, forcing Duensing, Lackey, and the Cubs’ hitters to be perfect. Maddon committed such an unforced mistake, narrowing the margin of error for his players, and shifting the tactical advantage to Roberts and the Dodgers.

But, I guess when you hit .117/.159/.217 with only two extra-base hits and two walks, that advantage matters a lot less.

Lead photo courtesy Jayne Kamin-Oncea—USA Today Sports