The Chicago teams of the 1880s were far more successful than those of the previous decade. The franchise captured the league pennant in half of the decade’s seasons; thus, despite losing the World Series in ‘86, the teams of this decade achieved one of the most successful periods in franchise history. Crafted by both A.G. Spalding and Cap Anson, this decade’s teams were defined by spectacular pitching and hitting, as well as a particular pageantry that helped convert the team to one suitable for the upper class’s enjoyment.

The Decade at a Glance

Spalding shaped much of the team from an aesthetic, innovative perspective, constantly figuring out new ways to monetize the team. He first served as the team’s secretary before becoming president in 1882 following William Hulbert’s death. Under his control, the team constantly experimented with equipment, from a square bat to a corked ball, both of which failed. His priority was making money, and he had no attachment to players if he could turn them for a profit or if they posed a threat to his leadership. His advocacy of the reserve clause was instrumental in its passing, enabling Chicago to retain its nucleus for the majority of the decade. By the end of the decade, however, Spalding had sold all of the team’s stars, save for Anson, and the team itself slipped down the standings as he began to concentrate on higher endeavors. Nonetheless, much of the early success can be attributed to Spalding’s roster creation.

These teams were anchored by incredible pitching, with Larry Corcoran and Fred Goldsmith powering the early ‘80s teams before giving way to future Hall of Famer John Clarkson. Corcoran began his career with the Cubs, while Goldsmith and Clarkson were acquired as young talent from other, cash-strapped NL teams early in the decade. Each of these pitchers was known for being wily on the mound–Corcoran was a switch-pitcher, Goldsmith threw a rare and devastating curveball, and Clarkson is credited with being the first to indicate pitch selection to the catcher–which led the equally ingenuitive Spalding to favor them. However, Corcoran and Goldsmith’s arms both gave out in the 1884 season, leaving Clarkson as the sole ace, and he was traded to Boston at the end of the 1887 season, signalling the end of the team’s impressive run.

Adding to the incredible pitching performances was a vaunted offense that led the league in runs scored and home runs each year of the decade, doing so mostly without cheating. Team captain and first baseman Cap Anson repeatedly hit in the high .300s and was often joined by right field er Michael “King” Kelly, who led the league in average, on-base percentage, and runs scored in both ‘84 and ‘86, as well as George Gore, who routinely hit in the .300s and led the league in walks in each of three seasons. A fouth offensive stalwart was left fielder Abner Dalrymple, who led the league in hits in 1881 and home runs in 1885, providing fine offensive talent until he, like Kelly, was sold after losing the ‘86 World Series. Many lesser-known names contributed offensively, and it seemed for years that Spalding could do no wrong with an acquisition, particularly if they were there for only a season. This high-powered offense brought fans to the ballpark wherever it was located, whether it be on the road or in various parks in Chicago.

er Michael “King” Kelly, who led the league in average, on-base percentage, and runs scored in both ‘84 and ‘86, as well as George Gore, who routinely hit in the .300s and led the league in walks in each of three seasons. A fouth offensive stalwart was left fielder Abner Dalrymple, who led the league in hits in 1881 and home runs in 1885, providing fine offensive talent until he, like Kelly, was sold after losing the ‘86 World Series. Many lesser-known names contributed offensively, and it seemed for years that Spalding could do no wrong with an acquisition, particularly if they were there for only a season. This high-powered offense brought fans to the ballpark wherever it was located, whether it be on the road or in various parks in Chicago.

In 1884, the league declared ground rule doubles would count as home runs, and the team’s stadium–with dimensions of 180 feet to left and 190 feet to right–produced 142 home runs, five times the previous record and 102 more than the league average that season. At the end of the season, the stadium was declared illegal for a variety of reasons, including it being a commercial venture, and the team had to finance a new stadium for the second time in under a decade. After months of scrambling, Spalding decided on the newly-developed area of West Side Park and constructed a park with slightly longer foul lines of 216 feet and an increased capacity of 10,000 seats. Though it was not as convenient as the Lakeview park had been, the city’s expansive public transit system helped negate the inconvenience, and the location of the new park in a well-to-do neighborhood prompted upper-class people to become fans, which was one of Spalding’s early goals.

This change of scenery seemed to reinvigorate the team as it again returned to first place after disappointing second-and fifth-place finishes in ‘83 and ‘84. With a new crowd of Chicago’s wealthiest inhabitants cheering them on from the stadium’s opening on June 6, 1885, the team began following Anson and Clarkson’s lead over the next two seasons, as they had done with Anson and Corcoran from ‘80-’82. In the ensuing two seasons, Chicago returned to blowing out its competition and lining Spalding’s pockets.

The Decade in a Game: September 11, 1886

The Chicago White Stockings entered the day with a three-game league lead over the second-place Detroit Wolverines, who had ended Chicago’s 14-game winning streak two days prior. The game was advertised as one embodying a vengeful tone, as the team was once again facing Charles “Lady” Baldwin, who managed to silence the vaunted offense that Thursday. The two teams had matched up evenly to that point in the season, producing fairly close affairs that were endlessly entertaining, but Chicago was hoping to break this streak and return to its offensive and defensive dominance before heading out on a month-long road trip.

The game drew a crowd of 15,000 with many other spectators taking to roofs of the park and nearby houses to watch the contest. Though attendance was not recorded for another eight years, this crowd was deemed one of the largest the team had drawn in several years, eclipsing the roughly 2,500 fans per game it drew in the earlier pennant-winning seasons. As was frequently the case this season and decade, the team put on quite a show for the fans, hoping to dazzle them with substance and style.

The pregame festivities lasted roughly an hour, beginning with a concert put on by the First Regiment Band and concluding with the team marching onto the field in the shape of a cross, led by its young mascot, Willie Hahn. Hahn, the son of a hat wholesaler whose shop was acro ss from the ballpark, earned the job in 1885 after Cap Anson’s racist abuse of the previous mascot, a Black man named Clarence Duval, became too unruly for Spalding’s liking. Hahn’s youthful–and white–face was adored by players and fans alike; he looked after the keys to the clubhouse, became Ned Williamson’s personal batboy, and had artists clamoring to paint his portrait. The six-year-old instantly became more trustworthy than a Black adult, and his presence at every home game for three years served as a reminder of this racism and the control Anson had over the team.

ss from the ballpark, earned the job in 1885 after Cap Anson’s racist abuse of the previous mascot, a Black man named Clarence Duval, became too unruly for Spalding’s liking. Hahn’s youthful–and white–face was adored by players and fans alike; he looked after the keys to the clubhouse, became Ned Williamson’s personal batboy, and had artists clamoring to paint his portrait. The six-year-old instantly became more trustworthy than a Black adult, and his presence at every home game for three years served as a reminder of this racism and the control Anson had over the team.

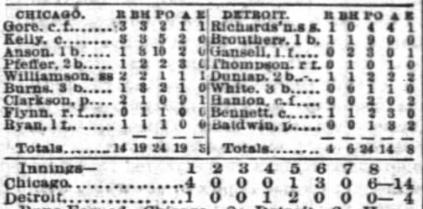

Once the game itself began, Chicago’s stars immediately made their presence felt, scoring four first-inning runs off Baldwin, with Anson driving in the first run and Fred Pfeffer, Tom Burns, and Clarkson each scoring a runner. These Chicago teams frequently scored multiple first-inning runs, setting the tone for the rest of the game and allowing their pitchers some margin of error, though it was hardly needed.

Indeed, Clarkson this day held Detroit to only six hits while recording seven strikeouts, besting his season average in both categories. His opponent, however, fared much worse. Baldwin gave up eight earned runs while only striking out two and contributing two errors of his own. It was evident early on that Chicago bested Detroit in all areas of the game from pitching to offense to defense. In particular, Chicago received excellent double plays on the part of second baseman Fred Pfeffer, third baseman Tom Burns, and shortstop Ned Williamson, who had collectively become known as the “stonewall” infield. Conversely, Detroit committed eight errors resulting in six unearned runs, preventing their bats from entertaining a comeback.

Jocko Flynn, the team’s third starter and utility player who only played one season with the club, hit a three-run home run in the top of the eighth to extend the team’s lead to 12-4, and, after two hours of play, the game was called due to darkness, and the 14-4 victory was finalized. Every member of Chicago’s lineup recorded a hit, and the top four of centerfielder George Gore, Kelly, Anson, and Pfeffer combined for 11 hits and 8 runs. It was the team’s 30th blowout of the season and 220th of the decade, over 50 more than any other team accumulated.

Chicago extended its lead over Detroit to four games, giving the team enough of a cushion to absorb a 5-game losing streak at the end of the month and win the league by two games. The strength of this victory led to even more disappointment in the ensuing World Series defeat, as Spalding believed his team should have won had they not become individuals unfit to play in front of the team’s elite audience. As a result, the teams of the remaining years of the decade looked quite different from this team and teams of the early ‘80s, as Spalding jettisoned any player that would turn him a profit, including Kelly, Gore, and Dalrymple, all of whom he charged with having character issues.

Though the decade ended on a sour note and spelled the end of the “Chicago White Stockings,” games like the September 11th, 1886 affair served as a reminder of how far the team had come in such a short period of time and how much talent graced the rosters of these teams. But this game in particular also afforded onlookers a glimpse of the end as the pageantry superseded the game and the changes Anson and Spalding instituted pointed to sinister characteristics that defined the decade’s final years and Major League Baseball’s future.

Resources:

Chicago Inter-Ocean, September 12, 1886, pg. 3.

Laurent Pernot, “Before the Ivy: The Cubs’ Golden Age in Pre-Wrigley Chicago,” (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2015).